If the Rich Aren’t Leaving It to Their Children… Who’s Getting the Money?

A cultural shift from inheritance to independence is reshaping how the wealthy think about their Wills – and charities need to take note.

In qualitative research interviews, when you speak to people about how they intend to manage the inheritance they leave their children, one theme comes up time after time – protection. The first thoughts most people have when they draft a Will is very simple…

How will I look after my family when I’m gone?

But there is a growing divide in how different groups answer that question. Increasingly, very wealthy people are redefining what “protection” means – and their answers look dramatically different from the instincts held by the rest of us.

For ordinary families, inheritance is still understood as a gesture of care. The sums involved are modest – UK data shows that people who receive an inheritance typically receive about £11,000.

It pays off a credit card, helps with a deposit on a flat, or fills the cracks left by insecure work and rising living costs. Inheritance, for most, is not an ethical dilemma; it is a kindness – a way to help a loved one out or give them a good start in life.

Very wealthy people, however, can leave a great deal more. And as a result, for many wealthy families, protection now means something very different. It means notleaving substantial sums. It means limiting inheritance, restricting it, or eliminating it entirely.

Among affluent parents, the worry is no longer that children might struggle without a financial boost – it is that they might get in trouble because of one. Wealth, they suggest, can weaken rather than strengthen.

This logic is spreading fast. Warren Buffett has long argued that the right inheritance offers opportunity without erasing the need for purpose. But it was Lenny Henry who captured the emerging mood when he said:

“Quite a lot of wealthy people now do this thing of not giving their children any money. There is a thing of not over-privileging your children if you are very, very rich because how are they going to learn?”

And the sentiment has clearly taken hold. Simon Cowell has said, “I’m going to leave my money to somebody. A charity, probably – kids and dogs. I don’t believe in passing on from one generation to another.”

Daniel Craig echoed the same discomfort: “I think inheritance is quite distasteful. My philosophy is to get rid of it or give it away before you go,”

And Sting added his own version of the philosophy: “I certainly don’t want to leave them trust funds that are albatrosses round their necks. They have to work. All my kids know that and they rarely ask me for anything, which I really respect and appreciate.”

Underlying this shift is a statistic that often gets repeated in the discussions we have with wealthy donors. They claim that 70% of wealthy families lose their wealth by the second generation and 90% by the third.

Its origins lie in a narrow study focused on family businesses rather than wealth as a whole. But it has survived because it resonates emotionally. The wealthy see the same pattern anecdotally – fortunes squandered, businesses sold, young lives ruined by excess. It has become a parable, guiding inheritance decisions irrespective of whether it is based on facts.

This philosophical divergence matters enormously because it is unfolding against the backdrop of an historic shift: an estimated £5.5 trillion will pass between generationsover the next two decades in the UK alone – mainly amongst families that are already more than comfortable.

This transfer has the power to reshape the economy and philanthropy. And yet the charities that may benefit from gifts in Wills may be entirely unprepared for the new inheritance culture taking shape.

Look at how most charity legacy marketing works today. Facebook ads promoting yet another free Will writing guide. John Lewis style TV ads broadcast in the afternoon. Generic calls to “leave a better world behind.”

The affluent older donors we speak to who are now now rethinking inheritance do not exist in these ecosystems. They rarely encounter charity ads on social media. They don’t watch much daytime TV. And perhaps most importantly, they have no interest in getting a free will written for them – nor do they need the advice.

The legacy research we undertake has given us a strong picture of what wealthier, older donors actually want when it comes to considering legacy decisions…

- clarity and seriousness,

- a sense of scale,

- evidence of impact,

- representation of people like themselves,

- and sustained relationship-building – not warm-glow sentimentality.

Which means many charities now face a widening gap. The people whose inheritance philosophies are changing fastest – and whose estates are likely to be the largest – are the very people they seem not to be speaking to. The future of charitable legacies will not be shaped by who sees a Facebook ad at 2:45pm on a Tuesday. It will be shaped by whether charities succeed in building genuine, trust-based relationships with those who have the most wealth and the most concern about passing it to their children.

As we have seen from speaking to many relatively normal – albeit wealthy – people, the disinheritance movement doesn’t seem to be an eccentric trend among celebrities. It is a cultural signal – one that charities ignore with some risk.

And the data backs this up. According to the UK Inheritance Expectation Report, 32% of Baby Boomers are reluctant to pass wealth to someone who has a different attitude toward money, and many express doubts about whether their children would use an inheritance wisely. “I’m not sure it would be used wisely. And that does concern me,” as one donor put it.

These aren’t fringe opinions; they’re becoming mainstream among older, wealthier cohorts. Many feel their children are already financially secure. Many feel a deep ambivalence about leaving large sums. And many are redirecting their resources – during life and after death – toward causes that better reflect their values. As summed up by another donor…

“They will get something, of course. But they are fine financially and there are some areas of work that I am very keen to fund.”

As “family first” stops automatically meaning “money first,” the question for charities is no longer simply how to ask for a gift in a will. It is how to best enter the inheritance conversation.

To reach this group, the reliance on free Will-writing guides as a promotional tool has to be reconsidered. Unless legacy fundraising evolves to take into account the needs of older, wealthier donors, charities risk being absent from the most consequential wealth decisions of the next generation – decisions that will be made not in response to a TV ad, but in private, intentional conversations about what really matters to people at the end of their lives.

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

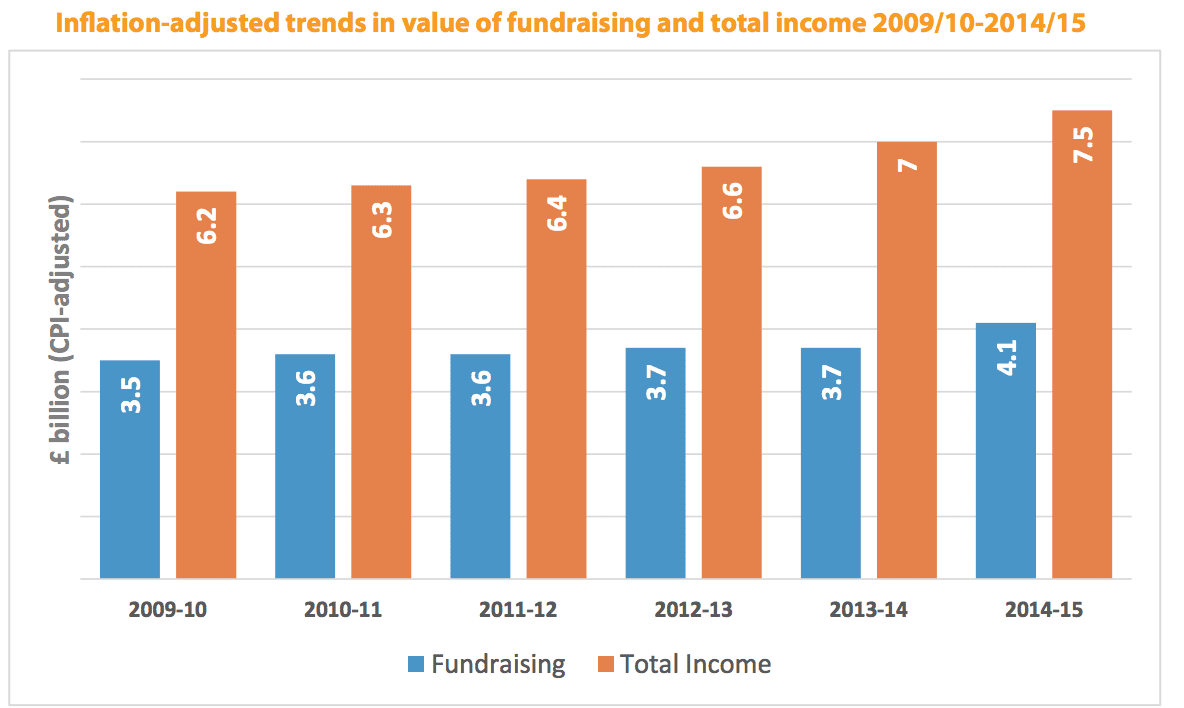

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?