Why fundraising feels worse than it used to

Betwixmas reflections on how trend-chasing, short-term approval and moral signalling have combined to undermine a craft built on trust and long-term value.

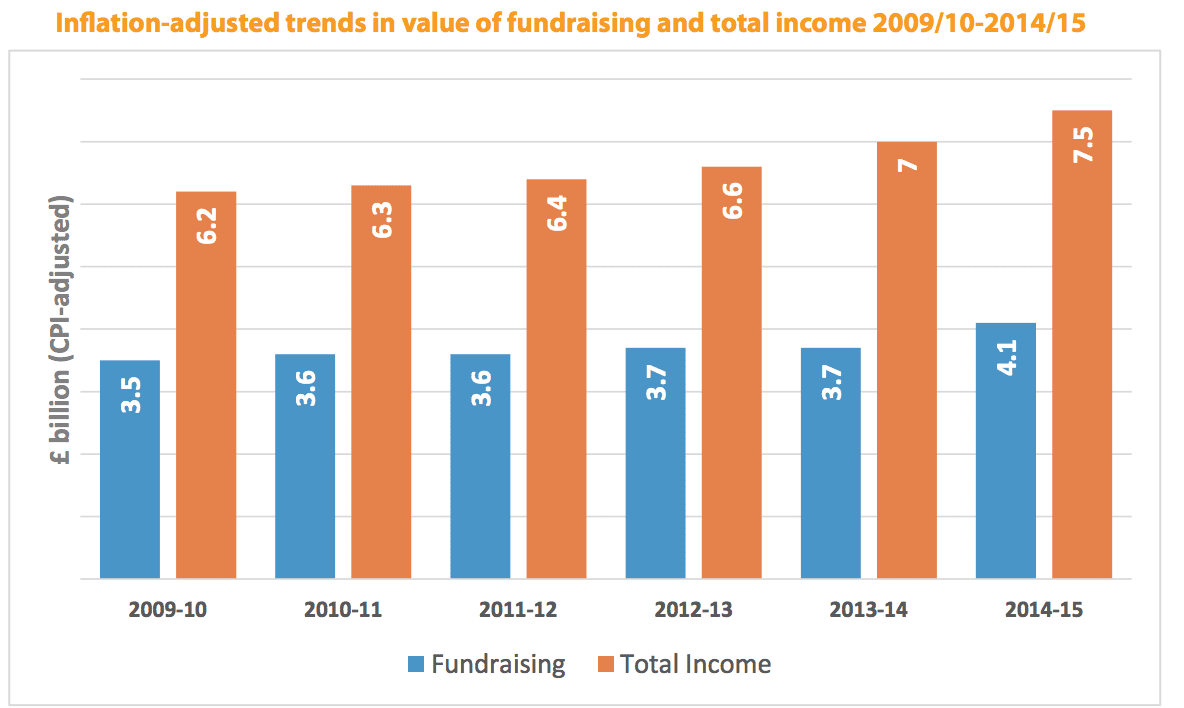

Regular readers here, and those of you who read my main blog over on substack, will know that I keep returning to the same question. Why, once inflation is taken into account, are we now raising billions of pounds less than we were ten or fifteen years ago?

One of my Christmas gifts this year brought that question back into focus. It was a copy of Enshittification by Cory Doctorow – a book about technology, monopoly and power – but as I read it, I found myself thinking less about Silicon Valley and more about fundraising.

The book’s core argument is that digital ecosystems become shitty when incentives reward signalling, entrapment and short-term approval rather than long-term value. That description reminded me of what has happened in our sector over recent years.

Personally, I don’t think fundraising has simply become harder. I’ve fundraised through recessions and financial crises before. But I’ve increasingly started to think that it has become structurally worse at its own purpose. And I believe that’s because the entire fundraising ecosystem has become distorted. Or as Doctorow describes so well, enshittified.

So what does his theory of enshittification actually describe?

At its heart, it demonstrates how systems move through three stages.

- They start by serving users well.

- As they grow, they begin to serve intermediaries and internal interests.

- Eventually, they extract value from everyone involved, while trapping users in the system.

The experience deteriorates, but the system persists because exit is costly and consequences are delayed.

Crucially, enshittification isn’t driven by people deliberately doing bad things. It’s driven by incentives that reward the wrong things.

So how does this translate to fundraising?

Traditionally, fundraising derived legitimacy from engaging people to give money to fund good work.

Money raised was the central test of effectiveness because it directly funded services. Today, legitimacy seems to increasingly come from other sources – being invited to speak at conferences, receiving LinkedIn love, aligning with favoured sector narratives, or simply being seen to be “in charge”.

The audience has shifted. And when the audience changes, behaviour follows.

Raising money has always been a slow process. You recruit supporters, engage them, they give, they increase their support and, if all goes well, they may eventually leave a legacy. Life obviously can intervene and the journey is rarely smooth, but as a model it broadly holds.

Impressing peers, by contrast, is faster and less complicated. It requires the right language, the right stances and visible alignment with prevailing norms. In a professional culture shaped by moral discourse, fundraisers are increasingly incentivised to optimise for being seen as culturally correct, rather than being effective.

By “culturally correct”, I mean fitting in with fundraising fashion – chasing after innovation without any strategic understanding of purpose, pursuing rebranding, or shifting focus towards a new audience, often younger donors.

Doctorow would recognise this immediately as a textbook case of signalling overwhelming function and making the whole thing feel, frankly, a bit shitty.

Look at what happens when a new fundraising approach is launched on LinkedIn, or a rebrand is announced. There is an outpouring of positive affirmation, typically from people at the edges of fundraising – agency staff, consultants and specialists whose professional interests align neatly with innovation or branding.

These initiatives are presented as brave acts of renewal. They are launched with confident language about relevance, inclusion, modernity and values. Sometimes they are accompanied by early claims about a huge number of new people engaged or an uplift in “consideration to give”.

And they are almost always declared an immediate success, often crowned with awards from people embedded in the same systemic loop.

Keep an eye on these claims over the long-term and, as my grandmother would have said, you’ll find out it’s usually all eyewash.

We’ve seen countless examples of award-winning innovations and brave new rebrands crash and burn a few years later. Yet the cycle continues. The obvious question is why?

Why, in the face of even modest amounts of research – a couple of phone calls to colleagues working at the charity involved – or a scan through annual reports – do projects destined to fail continue to get the green light, consuming vast amounts of energy and resources?

When a charity focuses on innovation or rebranding as a route to growing income, rather than analysing the strategic causes of stagnation or decline, it ends up draining its cultural capital. Recognition, trust, familiarity and the emotional shortcuts built up in donors’ minds over many years begin to erode.

This cannot be replaced overnight by a new visual identity, tone of voice or proposition. Cultural capital can only be preserved – or squandered.

Take a new name, for example. It’s exciting and usually presented as a way to engage new donors. But in reality, it forces an organisation to start again from zero in donors’ minds.

There are, however, immediate benefits for those closest to the rebrand:

- The internal lead gets to run an exciting project – and gets a boost in organisational and sector profile.

- The agency gains a portfolio case study – and similar reputational lift.

- Leadership experiences a sense of momentum and control.

The costs, by contrast, are delayed and dispersed:

- Donor recognition weakens

- Giving habits are broken

- Response rates soften – often dramatically

- Trust erodes incrementally

These resets destroy value. Starting again may feel innovative, but it is also existentially dangerous. The downside is not that things stay as they are – the downside is the loss of years of accumulated cultural value.

Doctorow’s enshitification pattern fits this scenario perfectly. Short-term professional reward is extracted, while long-term institutional value is quietly drained.

Crucially, this extraction is rarely framed as a technical trade-off. Rebranding and innovation are instead presented as moral acts – ways to do good by reaching new audiences, raising more money, or avoiding being left behind.

But what’s the kicker?

When innovation becomes a moral badge, the fundamentals of fundraising don’t disappear – they’re simply deprioritised and starved of attention, leaving those who steward them doing vital work without the status or support they deserves.

As resources and focus shift elsewhere, fantastic people working in these disciplines can feel less valued. Confusion and disengagement follow, not because the work has become less important, but because excellent teams are left under-resourced or forced to navigate a new set of self-imposed obstacles.

What gets forgotten in this transition is that these so-called “older” systems paid for services, built donor trust, and created resilience through habit. When organisations discard that accumulated advantage, they don’t become more ethical or more effective – they become weaker.

Doctorow would describe this as another classic enshitification move – the past is reframed as friction.

Donors are recast as entitled or misaligned. Stewardship becomes “pandering”. Gratitude becomes suspect. When income falls, the explanation is cultural rather than strategic – the donors were the problem all along.

This is simply donor-blaming. Donors want to be part of organisations focused on making the world a better place. They give to make things better. Most want little more than to know their gift is appreciated and put to good use. Yet there are parts of the sector that appear to treat this essential work as inappropriate, too expensive, or too low-status to prioritise.

Charities exist to turn money into mission. Destroying accumulated donor value in pursuit of peer recognition, fame or social credit harms the very people charities exist to serve.

Look at many of the fundraising powerhouse charities of previous decades. Today, they struggle. Some maintain scale through costly face-to-face recruitment whilst others chase successive innovations or commercial solutions as income declines – often without stopping to diagnose the underlying strategic problems. The result is a steady stream of stories about redundancies and service closures in the sector or national press. Who wants that?

Which brings us back to Doctorow’s most unsettling insight. Systems don’t collapse because of villains. They collapse because incentives drift, feedback loops break, and quasi-commercial approaches to extraction become more rewarding than old-fashioned stewardship.

In a world where most money will always come from older donors, value is cumulative, fragile and slow to rebuild. When organisations treat rebranding and innovation as financial springboards rather than risks, they burn capital that is expensive and painful to replace.

The danger is that this erosion rarely feels like failure at the time. In fundraising, enshittification doesn’t arrive with cynicism, it arrives with applause – with likes, hearts and peer approval that mask the slow loss of underlying value.

That is why resisting it requires a deliberate reset of what organisations choose to reward.

First, charities need to re-anchor legitimacy in outcomes rather than applause. Money raised over time, donor retention, lifetime value and legacy growth must reclaim their place as the primary tests of effectiveness. Conference invitations, awards and LinkedIn affirmation may feel validating, but they are weak signals. A useful discipline is to ask whether a major initiative would still be pursued if there were no sector PR, no awards ceremonies, no LinkedIn posts - in short no one would hear about it outside the world of the donor.

Second, accumulated donor value must be treated as a protected asset, not a sunk cost. Trust, habit and recognition are not incidental by-products of fundraising; they are hard-won assets built through years of investment. Any rebrand, platform change or innovation should be required to state clearly what existing value it puts at risk. Starting again may feel energising, but it often amounts to the quiet destruction of years of compounded advantage.

Third, feedback loops must be restored by listening to donors rather than sector narratives. When income falls, the temptation is to reach for cultural explanations or ideological comfort. Doctorow would warn that this is exactly how systems drift – evidence is replaced by preferred narratives and consequences are deferred. Donors are not an inconvenience to be managed around. They are core to the system, and their behaviour is the most honest signal charities receive.

Finally, incentives must be realigned so that stewardship and patience are rewarded, even when they are unfashionable. If careers progress more quickly through driving innovation than through the slow accumulation of value, behaviour will inevitably follow. Legacy, direct mail and stewardship are not conservative holdovers – they are long-term value engines and should be entrusted with the influence and authority that reflects their contribution. Treating them as such is one of the most reliable ways to resist enshittification.

Resisting this drift does not mean entirely abandoning innovation or retreating into nostalgia. It means restoring strategy to the centre of decision-making – applying a discipline that focuses on long-term value over short-term affirmation, and judging choices not by how they land in the moment, but by what they sustain over years. For example, that means approaching rebranding not as a design exercise, but as a question of donor experience – what is recognised, remembered and trusted, and how easily supporters can continue the habits that fund the work.

Fundraising has always been a mixture of art and science built on memory, trust and continuity. Its strength lies not in novelty for its own sake, but in the patient accumulation of belief – belief in organisations, in causes, and in the idea that giving makes a difference. Enshittification takes hold when that craft is treated as expendable, when applause replaces evidence, and when long-term value is traded for short-term recognition. Resisting it is not an act of conservatism, but of care – care for donors, for institutions, and ultimately for the people and the missions that depend on us.

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?