Here's a fundraising strategy for you: Why don’t we just tell donors we are broke?

When charities once admitted they were overdrawn – and donors loved them for it

For all the sophistication that surrounds charity finance, fundraising strategies, and donor-care programmes, one simple truth still seems oddly difficult for many organisations to embrace – donors understand that charities sometimes run short of money. In fact, they expect it.

Speak to almost any major donor – particularly those accustomed to managing substantial personal or corporate wealth – and they will tell you that they know charities need healthy reserves. They recognise that responsible stewardship demands money in the bank. What they don’t understand, however, is why a charity insists it cannot act or cannot help without further gifts, when its published accounts show millions sitting quietly in reserve.

It’s not the existence of reserves that troubles donors; it’s the curious reluctance to use them at times of emergency. Donors know that charity finances ebb and flow. They know that restricted funds can’t be spent freely, that cashflow matters, and that demand rarely checks the bank balance before arriving at the door. What jars is the sense that charities sometimes speak as though those reserves don’t exist.

This wasn’t always the case. A century ago charities often spoke far more plainly.

When “Waifs and Strays” said the quiet part out loud

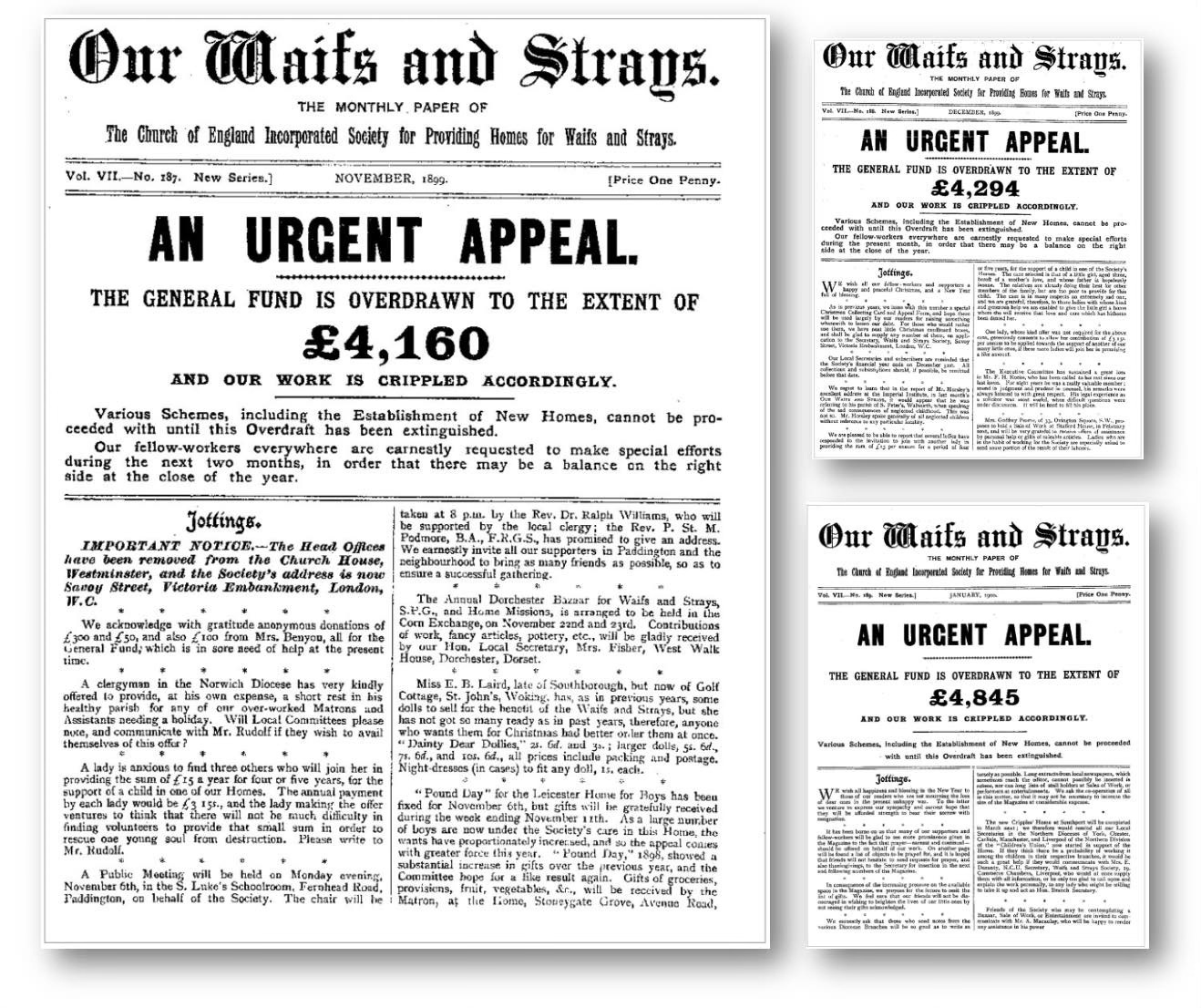

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, the Children’s Society – then known as the Waifs and Strays Society– took what many might see as a bonkers approach to talking about finances in their appeals.

Each year, as Christmas approached, their monthly newsletter, Our Waifs and Strays, carried a stark headline – An Urgent Appeal. In the November, December, and January editions, the Society announced – boldly and without embarrassment - that the General Fund was overdrawn. Not merely “under pressure,” not politely “in need of support,” but, in 1899 for example, overdrawn to the extent of £4,160 in November, rising to £4,294 in December, and reaching £4,845 by January 1900 - all accompanied by the sobering refrain that work was ‘crippled’ accordingly.

To place those figures in perspective, this would equate to well over half a million pounds today.

These appeals were printed in large, unmissable type, occupying the front page like a public confession. They did not pretend that life-changing work could continue without new donations – nor did they attempt to disguise the scale of the financial mountain they needed to climb.

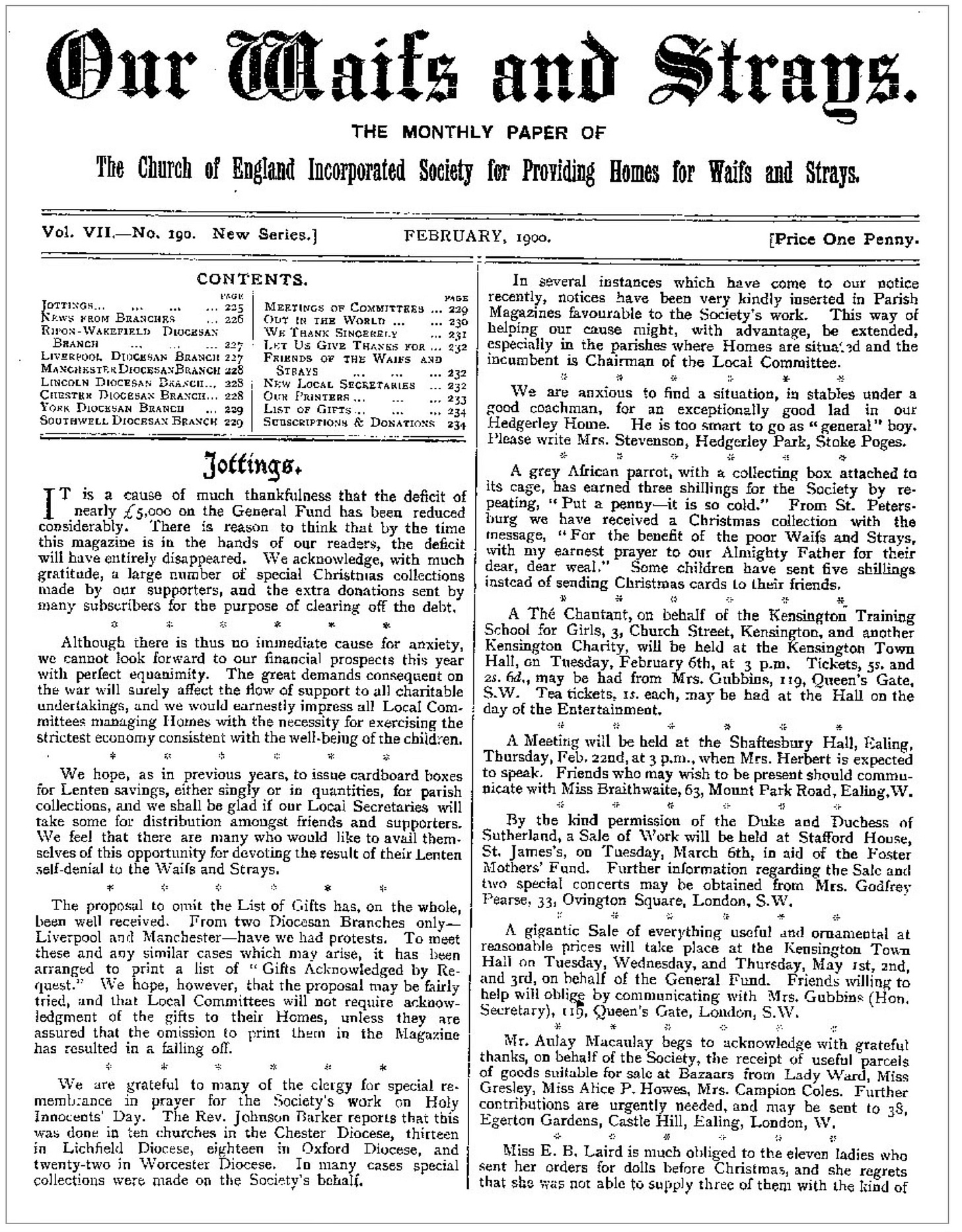

And then, February’s edition arrived with a small but triumphant statement: the crisis had passed. Extraordinary generosity had restored the balance. Homes would continue to operate; new children could be received; the work could proceed with renewed strength.

It was a ritual, repeated year after year, of scarcity and salvation. But it looks like it worked. Donors responded because this was real need – urgent, and unvarnished.

What modern donors still understand

Despite the evolution of charity communications, donors haven’t lost that understanding. They expect that charities should use their reserves when the circumstances demand it and that surges in demand may exceed planned budgets.

They grasp the cyclical nature of money. What gets them scratching their collective heads is the growing sense that reserves aren’t being used when the need is unmistakably urgent – creating the impression that decisions are being driven not by common sense or compassion, but by the internal needs of the charity rather than the needs of the people it exists to help.

So what’s stopping us?

If donors are comfortable with financial vulnerability, why are charities uncomfortable?

Perhaps it’s something else, like branding, that we’ve adopted from the commercial world?

CEOS, Trustees, finance directors – often from commercial backgrounds – may instinctively recoil at public declarations of overdrafts, deficits, or temporary shortfalls. In the commercial world, admitting that the organisation is overdrawn can signal mismanagement or risk. Obviously, we need disciplined, rational financial systems, but sometimes it might cause us to unintentionally apply commercial norms to charitable storytelling.

In business, you never announce you’re broke.

In charity, it might be at the heart of the best appeal you ever send out.

Financial insecurity as the focus of an appeal

Perhaps it’s time to reconsider the old rhythm of the Waifs and Strays Society – the drama, the annual crisis as narrative device and the unapologetic clarity. The fact is the straightforward statement of organisational need recognises that donors can handle the truth – charities need to spend the money they are given. That’s why donors give it.

Modern charities hold greater reserves, manage larger budgets, and operate within more complex regulations than their Victorian founders ever did. But the essential principle remains the same:

Donors are far more likely to support a charity that demonstrates it needs help, than one that only pretends that it does.

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?