What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

This week fundraisers in the UK have been lucky enough to get their hands on two new studies packed with some great insights about what's happening in the market.

CAF have released the latest update to their ongoing study into donor behaviour, UK Giving and the IOF have published Fundraising for Impact, a survey of over 100 charities that looks at priorities and plans for fundraising over the coming years.

It’s a great comparison. On one hand we can see what fundraisers are planning and on the other we see what donors are doing. Weirdly (or not so weirdly) they don’t really correlate.

Let’s kick off by looking at some of the highlights from UK Giving 2019.

I particularly look forward to this report as there are few longitudinal studies published that give us an insight into the long-term changes in donor giving behaviour. Some people criticise CAF as the study is based on donor surveys rather than analysis of hard data. But asking similar questions over an extended period of time has real merit.

And it’s the length of time that this study has been operating that gives us some serious insights into how we have been functioning as a sector. So I’ve gone back and looked to see what has happened over the past decade or so and found that pretty much, come what may, a similar proportion of donors give a similar amount of money to charity – every year.

Yep. Nothing much is changing.

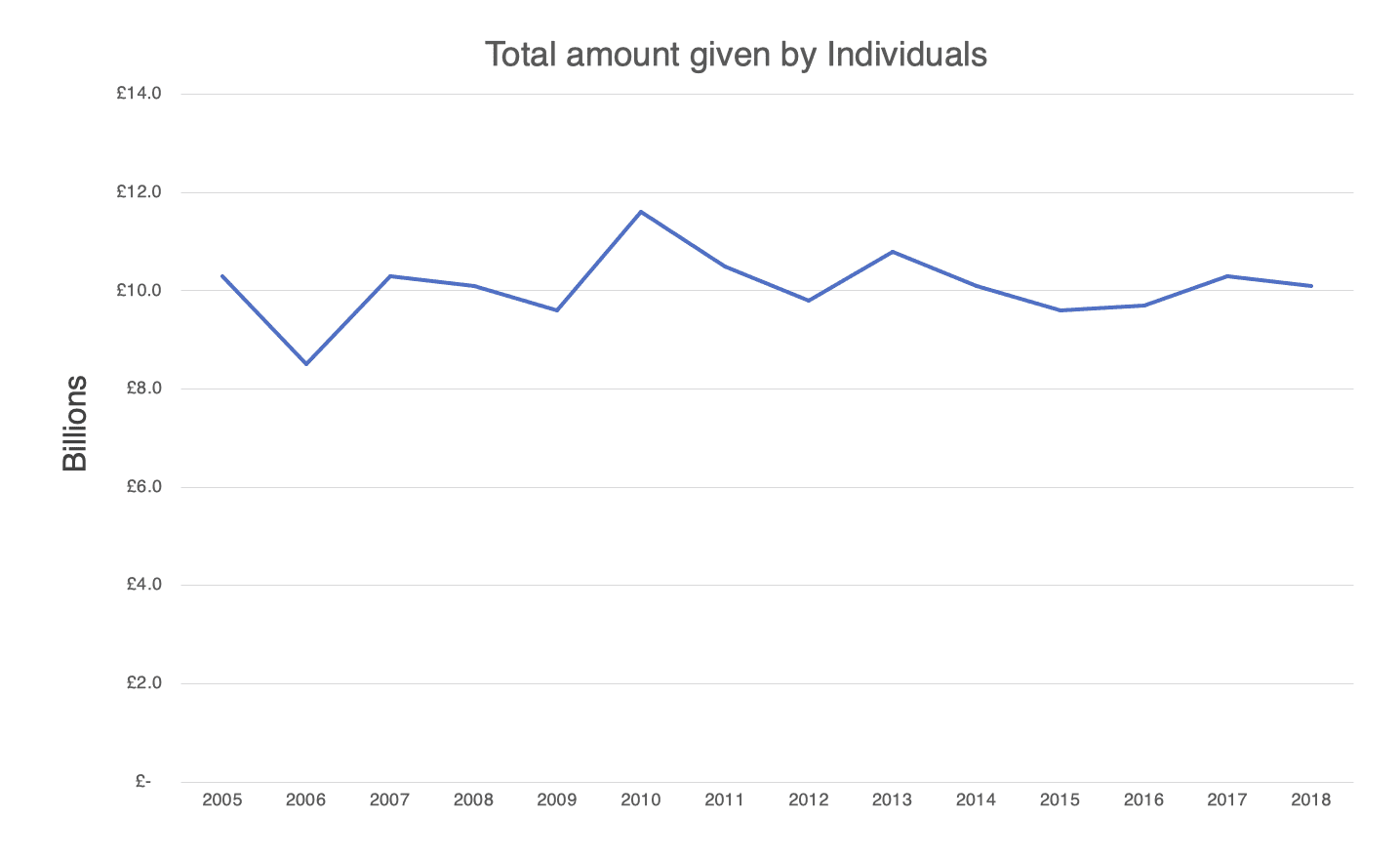

In the face of the various charity scandals and the introduction of innovations like mobile giving, the continuation of long-standing programmes like Face to Face and the growth of digital fundraising, the amount given remains stuck at about £10 billion a year.

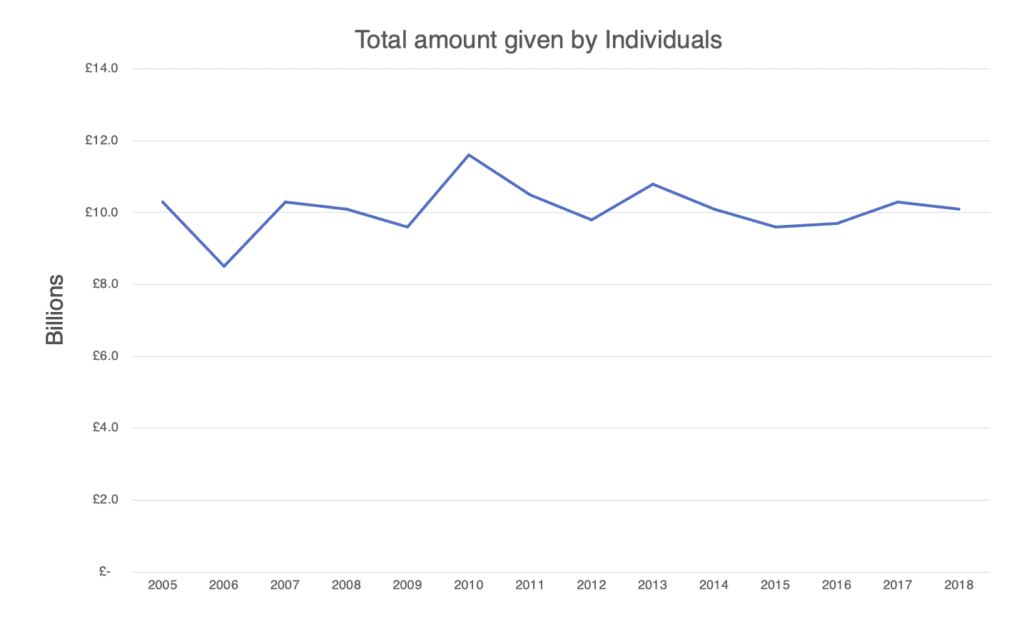

Take a look at this chart that goes back to 2005.

There are a couple of peaks in 2010 and 2013, that occur at the same time as large international appeals (the Haiti earthquake and Pakistan floods in 2010 and the Syria crisis and Typhoon Hiyan in the Philippines in 2013). But what's remarkable is how stable income is. Even the fundraising crisis in 2015 hasn't dented it much.

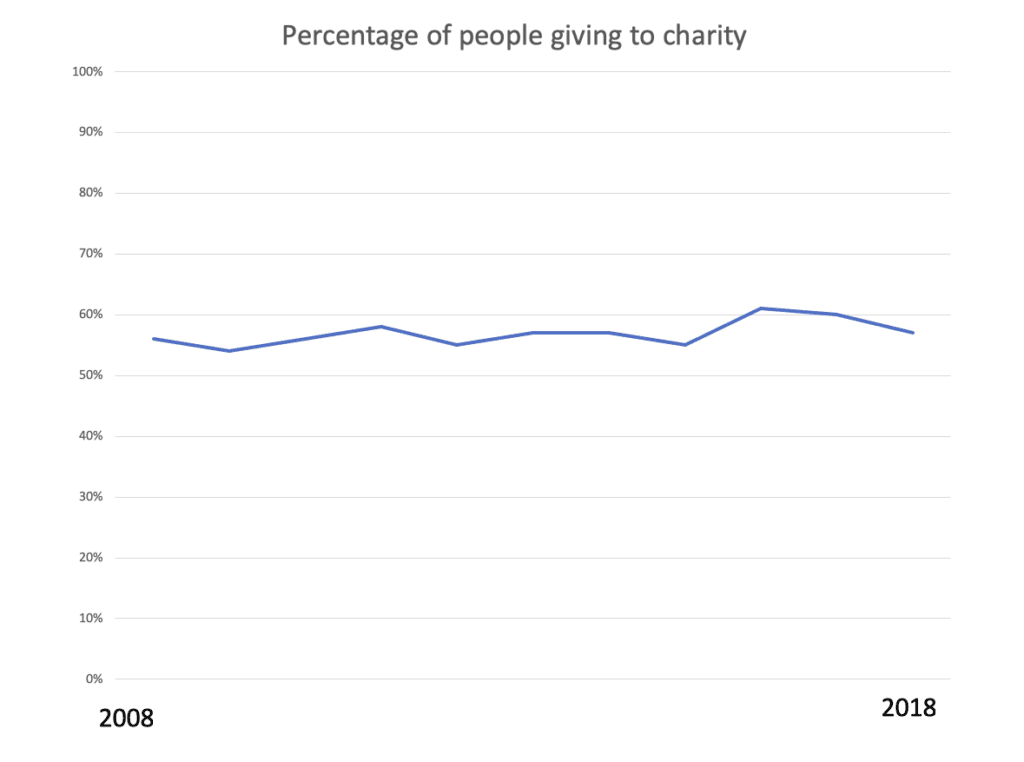

And when we look at what percentage of people are giving each year, we see that it's also pretty stable at just under 60%.

Even the number of people giving via direct debit hasn't changed that much. Back in 2008, 29% of people were giving by direct debit. It got up to 32% in 2012 and following some wiggling about over subsequent years it has now sneaked up to 33%. That's good news, but in the face of the many millions that must have been invested in recruiting new regular givers it's surprising to think that it's had so little impact on the sector's bottom line.

Now let's take a look at the IOF's, Fundraising for Impact. Remember, this is based on a survey of fundraisers where they are asked about priorities and plans for the future. What's the most important area of future focus for them? Take a look at this chart – it's recruitment of new supporters.

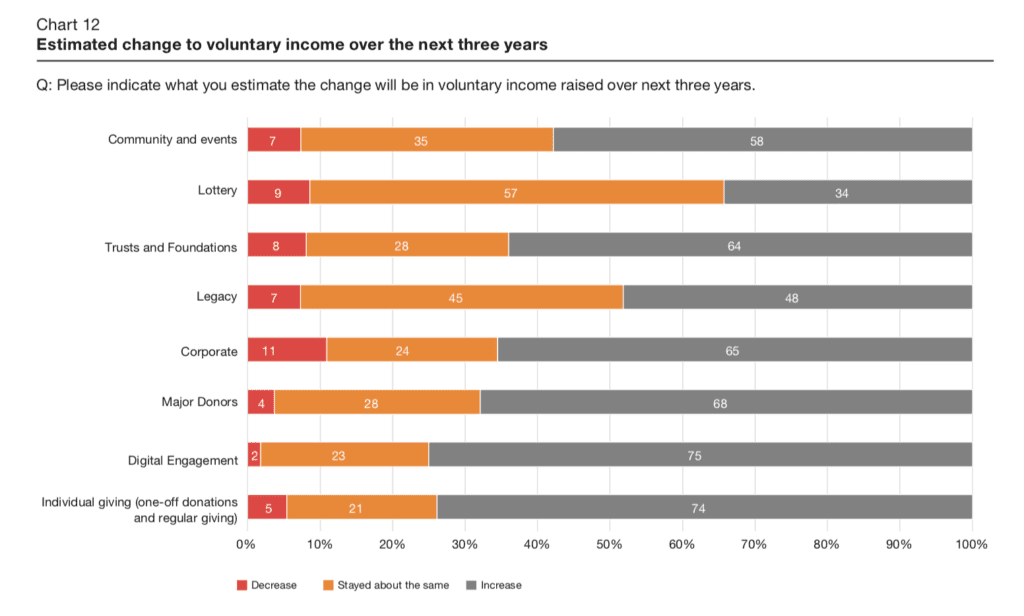

The survey found that the majority of fundraisers estimated that there would be growth of at least 10% in most areas of voluntary income over the next three years – with individual giving and digital engagement as the most important areas – as detailed in the bottom two bars in the following chart.

Interestingly, the main area where we are seeing growth at Bluefrog is with legacies (along with mid-value). And less than half of the charities surveyed saw legacies as an area with potential.

But the main point is that in the face of years and years of stagnation, three-quarters of fundraisers surveyed saw individual giving as offering great potential for growth – with digital engagement as central to this ambition

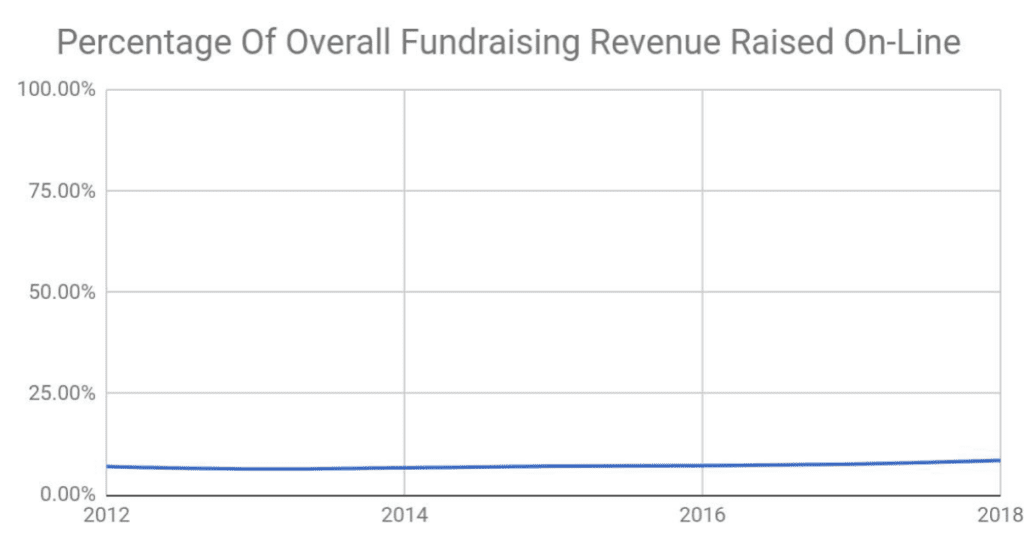

Now I don't want to offer up more reasons to disappoint but Simon Scriver pointed out at the Donor Love conference in Las Vegas that digital giving isn't necessarily going to come racing over the hill to save us. Blackbaud's most recent Charitable Giving Report shows the percentage of overall fundraising revenue raised on-line is growing incredibly slowly and is still stuck at under 9%.

This is an international study, and some organisations are obviously doing much better (generating online revenue of up to 30%). But if you aren't doing well at digital at the moment, you'll need good reason to think you can significantly boost income without a serious level of investment (and a very strong individual giving programme) in the next three years.

So what does all this mean?

First, there is a core group of donors who appear to be incredibly reliable no matter what.

And brilliantly, the lessons over the last few years following the fundraising crisis seem to have been learned. The best part of two-thirds of charities report that they are focusing on improving the donor experience and growing relationships with existing supporters.

However, from others studies, we know that the vast majority of giving is undertaken by a relatively small group of people.

And if we have a very large number of charities looking to increase income from individual giving, the donors they target are going to come under serious pressure. It's a no-brainer to say that without growth, the desire for new donors and new money is not going to be satisfied. After all, there is precious little evidence that there is a massive untapped resource out there just waiting to be asked for help.

So what should a charity do in an increasingly competitive environment?

There are three key elements to work on.

Number one is to focus on your most valuable donors. By that I mean those who actively care about your cause - who have a point of real connection. Mass recruitment will struggle in this new competitive post-GDPR world. The successful fundraiser is going to need to understand what donors want and deliver it - asking at the right time, asking for the right amount and for the right reason. Which brings me to point two.

Fundraising for Impact details what charities are planning - not how they will do it. Though fundraisers want to focus on improving the donor experience, this study doesn't give us any idea of what techniques they might use to increase their understanding of what donors want and need.

This direction must come from donors and the best way to unlock this insight is to start speaking to the people who actually give. It's time to push some budget into this area and listen to donors - through well structured research.

Finally, think carefully about what areas of fundraising have the most potential for growth. What we've done in the past isn't necessarily going to work in the future. And legacies are a key area here.

As Rob Cope of Remember A Charity pointed out last night on Twitter:

"Market growth in legacies is bucking trends. More people now leaving gifts, but also more charities asking and benefiting for first time. Next decade will be biggest transfer of wealth in history. Those who invest in legacies now stand to benefit most, including market entrants."

From the IOF's study, it looks like there are a number of charities who don't appreciate just how important this will be.

Both publications are incredibly useful, but they should be read in tandem. There are some very generous people out there, but they are not going to want to water down their giving across a large number of causes. Indeed, as donors mature, they tend to weed out the charities they don't value from their philanthropic portfolios (you can read more about that here). And those choices are not necessarily based on an appreciation of which charities have been nicest to them.

As Alex Hyde-Smith said at #AFPIcon in San Antonio this year:

"We can only grow fundraising if charities focus on their mission of what society needs and values. We can't keep trying to get more if we are not seen to be offering great value in return."

To my mind, that is what will drive the most growth.

Best of luck!

A final point. We are currently working on a sector wide research study looking at how donors decide how they share out their philanthropic budget and could include one other UK charity – drop me a line at Mark [@] bluefroglondon.com if you are interested in getting involved.

Tags In

Related Posts

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

How do donors manage their philanthropic budgets?

[…] Mark Phillips offers up an objective look at the state of giving and how to move forward. […]