Face to face fundraising from 1910

Many people seem to think that large-scale face to face fundraising was first developed by Greenpeace in the 1990s, but it's been around far longer than that.

ActionAid were recruiting child sponsors in the 1970s by going from door to door. And Oxfam were using press ads to recruit people to collect regular pledges from their friends and neighbours in the 1960s.

But that's nothing to what the YMCA was doing back at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Around the world, new YMCAs were built with money raised through what became known as the Lightning Canvass.

The idea was simple. Get a group of young men, divide them into teams and send them out on the streets for two weeks to recruit donors who would give on the 'Instalment System'.

It was the brainchild of Charles Sumner Ward, who could well be described as the godfather of modern fundraising.

Charles was General Secretary of Grand Rapids YMCA in Michigan. And he had a problem that many CEOs of today's small charities might recognise. He had to spend most of his time fundraising rather than doing 'real' work.

As a result he came up with a plan. In January of 1892, he asked his directors to close down their desks for part of each day so they could give "wholehearted support to an intensive, organised effort to raise the Y's budget at the beginning of the year". At the heart of the idea was a dislike of fundraising that resulted in a desire "to get the agony over with quickly."

The plan worked brilliantly. Together with a group of volunteers, they raised the year's budget within a few days. For the next five years, Ward repeated the exercise with similar results.

Soon other YMCAs were asking for his advice. He introduced them to his approach and success followed success. He raised £103,000 for Boston YMCA, £64,000 for Montreal YMCA, over £160,000 for Toronto YMCA and a massive £200,000 for Philadelphia YMCA (which would be worth over £16,000,000 today)

In 1912 he brought the technique to the UK and helped set up campaigns for a number of new British YMCAs, including one for Manchester YMCA. Having searched the archives of The Manchester Guardian I've found out what happened.

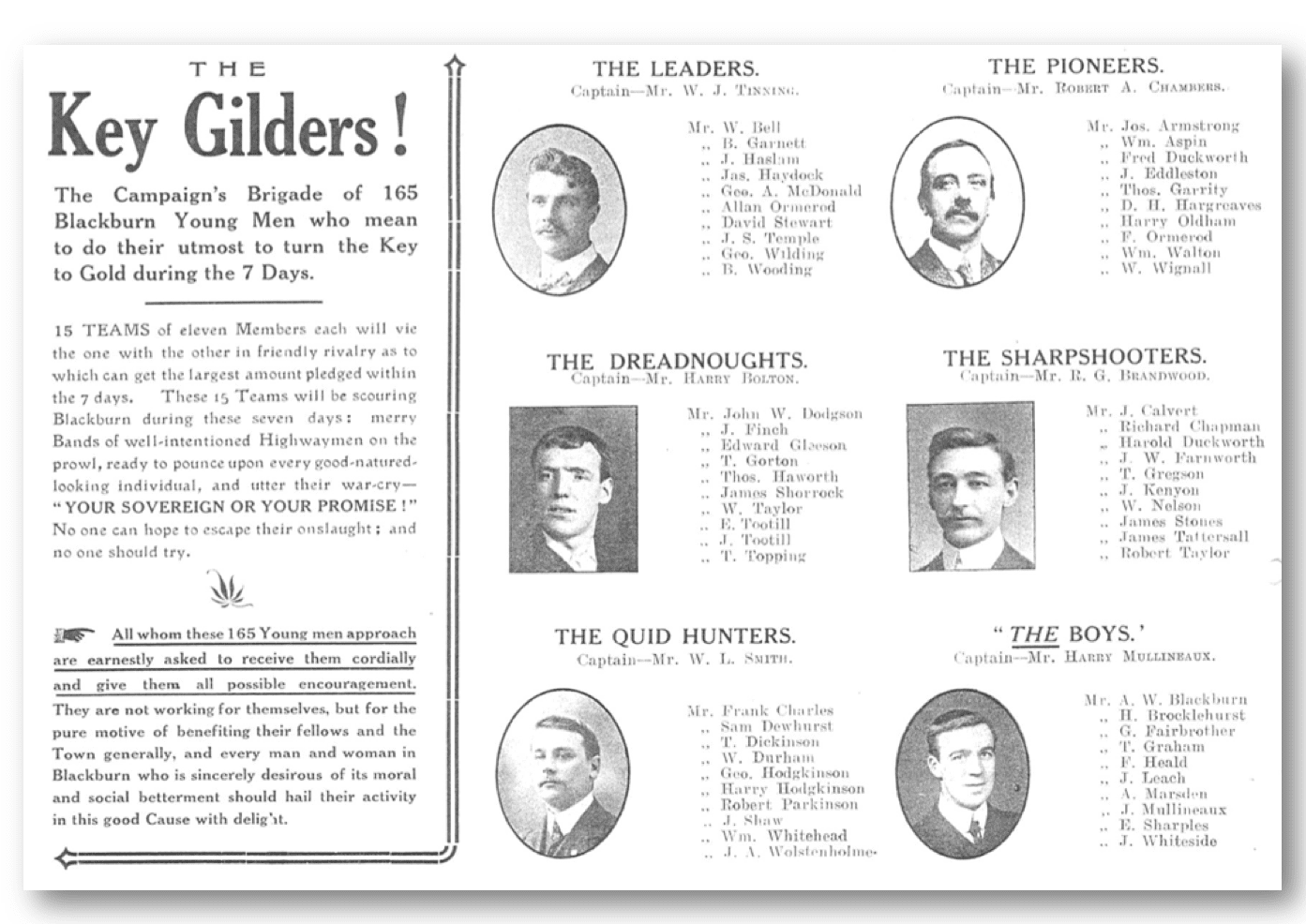

350 different volunteer fundraisers working in teams known by such donor friendly names as The Hustlers, The Tender Heart Ticklers and The Gold Chasers raised £14,000 in twelve days. They did this, in their own words, by...

"...scouring Manchester during the campaign...merry bands of well-intentioned highwaymen on the prowl, ready to pounce upon every good-natured-looking individual with their cry, 'your money or your promise.' "

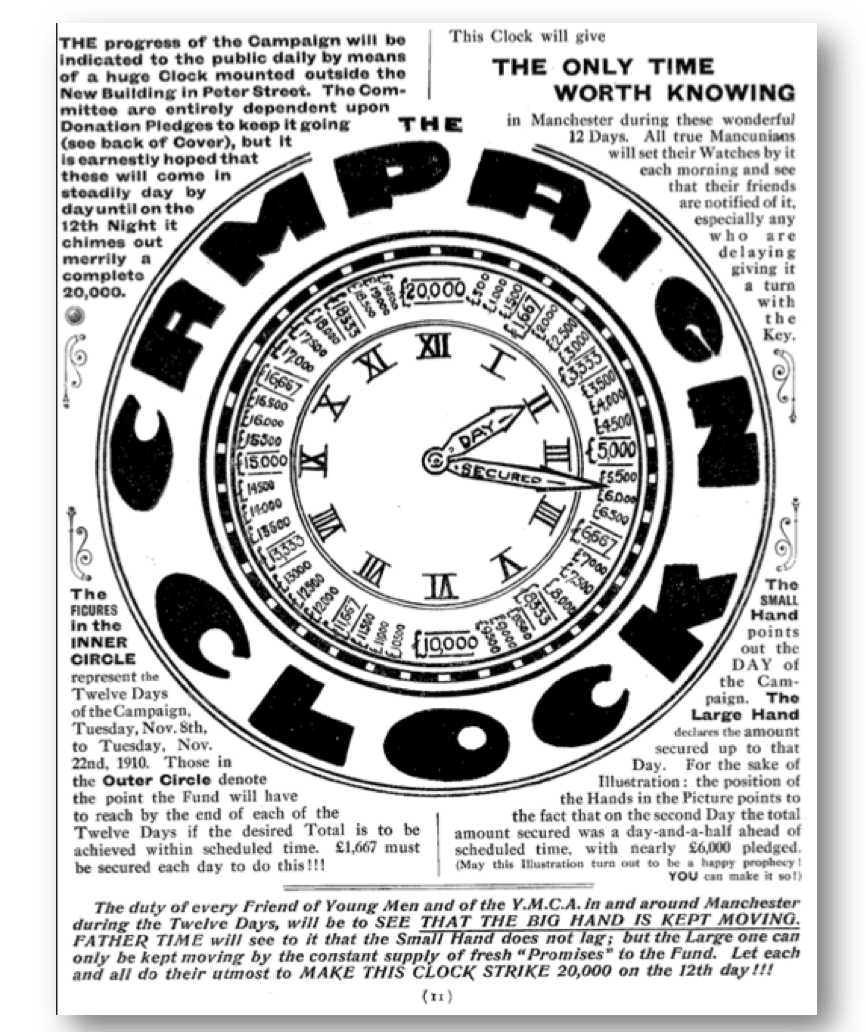

To build excitement they erected a huge fundraising clock in Manchester city centre that allowed everyone to see the money rolling in. It was so important to the campaign that it took pride of place in the campaign brochure...

Sadly, they fell short of their target by £6,000, but the regular payments on the 'Installment System' made up the difference.

They generated these by encouraging donors to complete a forerunner of the direct debit form. It was designed to neatly dovetail with the the clock...

The success of these campaigns wasn't down to luck. Ward had tested and proved his strategy many times. And luckily, the Manchester Guardian on the 7th of October, 1912, detailed just a few elements of the approach...

"In money-raising, the quick campaign method had proved itself to be the very best method up to the present. The best time for holding the campaign was towards the end of January, because by then dividends and rents had recently been paid, and it was the time when many people and firms set aside amounts for the year's gifts...they should not overlook the importance of having a luncheon or dinner on the eve of the campaign to which they should invite a large number of possible subscribers."

But even in 1912, there were dissenting voices that weren't convinced that face to face fundraising was the way forward. The Manchester Guardian reported the concerns of the Rev. Stanley J. Hersee who thought the effect of a lightning campaign would be disastrous...

"It was really a spasmodic effort concentrated into five or ten days; they had a tremendous reaction, and the backwash was a bad thing. Many people were growing tired of the sort of 'revolver, your money, or your life' campaign."

It just shows that even when it comes to the attitudes of donors there's nothing new in the world of fundraising. Apart from the fact that today's face to face fundraisers look a little different from their Edwardian counterparts...

With thanks to Gary Shearin for providing the images.

Tags In

Related Posts

4 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

Hi Brian

The assumption that so many people make is probably based on the almost mythical status that the Greenpeace face to face programme generated.

It shows that innovation isn’t necessarily as effective as getting hold of a few history books and seeing what our fundraising predecessors were up to.

Thanks for commenting and the insight.

I just want to say thank you. The perspective you’re bringing to the industry, Mark, thanks to your historical reviews, is a decided relief. I think we sometimes assume that the best ideas are still undiscovered, when in fact some of the best ideas were discovered long ago and have simply been forgotten.

Hi Tom

I always think the best place to start any innovation project is in the history books.

It never ceases to amaze me what can be uncovered when you start digging around in the archives.

The trouble is that historical research is much harder than sitting in a room ‘blue skying’. But I know where I’d put my resources.

Thanks for commenting.

Good stuff Mark. Face to Face strikes me as similar to the Hospital Saturday funds that kicked off in the 1860s and 1870s – where towns were divided into constituences, each with a collector, to collect contributions from workers.

Many evolved into social insurance type schemes, but it was often a good blend of philanthropy and mutualism. And I seem to remember reading in the archives about complaints about the collections!