The misdirected power of the brand

Some people think I don't like branding. They are wrong. I love great brands. The trouble is that I don't think many charity brands are very well managed and there are a growing number of pieces of research that serve to confirm my beliefs.

I thought I'd share a few of them after reading the recently published Charity Brand Index which features the UK's top 100 charity brands.

It was compiled using survey data from 3,032 people, who were asked about their awareness of charities and the impression they had of them.

"Respondents were asked about their awareness of 30 charities randomly selected from the list of 150. After highlighting those they were aware of, they were then assigned a maximum of five charities to focus on in the main survey. Respondents were then asked their views on these 150 charities, the metrics subsequently making up the top 100 ranking being: relevance, distinctiveness, familiarity, trust and impression.

‘Consideration to donate’ acted as a proxy for all these measures, which were then all multiplied by prompted awareness to ensure that charities which were loved by a few, but had low awareness, did not achieve a disproportionate rank."

The top ten were:

Macmillan Cancer Support

Cancer Research UK

NSPCC

RSPCA

BBC Children in Need

British Heart Foundation

Comic Relief

Marie Curie Cancer Care

RNLI

British Red Cross

Macmillan, with voluntary income of less than a third of Cancer Research UK, were surprise winners. Their high familiarity score and an extremely positive impression of the brand lifted them clear of the competition.

But what does all this actually mean? What is a brand actually worth?

A study published earlier in the year attempted to estimate the value of American charities. They gave top spot to the YMCA (a charity that doesn't even feature in the UK list) with a worth of almost $6.4 billion. The charity with the best brand image was the American Cancer Society.

A different set of criteria was used to build the US list. They included such factors as size of budget, potential for future growth, volunteer numbers and news coverage in their analysis.

These differences in approaches seem to back up John Murphy's thoughts on brand valuation. John founded global branding consultancy, Interbrand, and has a refreshingly honest opinion on the subject…

"Brand valuation is a 'social science' not a 'physical science'. Valuation opinions will always be just that – opinions."

For me, any assessment of charity brand value has to be based on the additional income it will help generate. The fact that someone knows that a charity exists or answers a specific need is worthless if it doesn't translate to the bottom line. And 'propensity to donate' doesn't quite cut the mustard for me.

It's why reports and studies that inflate the value of brand building activities are so dangerous. Branding is seen by a growing number of people as a universal panacea to a charity's ills and there is precious little evidence to back up their belief.

Branding just doesn't seem to be solving the deep-seated problems the sector faces.

Joshua G2 undertake research into which brands are most loved and hated by the British public and have included charities in their studies. Last year they found that Cancer Research was most loved (followed by Macmillan, RSPCA, NSPCC and PDSA) and Christian Aid was most hated (followed by War on Want, Oxfam, The Salvation Army and RSPCA). Results for 2007 are here.

But what's interesting is to try and uncover why charities engender these emotions.

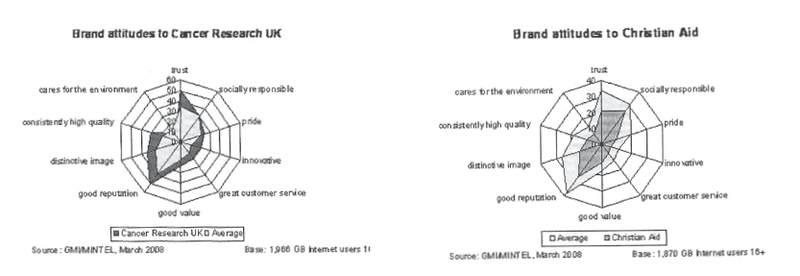

Luckily GMI / Mintel did their own study to try and uncover the attitudes underling these emotional reactions (also published in 2008). They assessed charities on a variety of characteristics. These included, trust, social responsibility, pride, innovation, great service, good value, good reputation, distinctive image, consistent high quality and caring for the environment. These were mapped out on radar charts. I've reproduced those for Cancer Research UK and Christian Aid. The darker shape represents the scoring for the charity, the lighter shape is the average for all charities they analysed.

You can see that Cancer Research UK scores very highly on trust and on good reputation. Christian Aid in comparison does very badly on both indices. But what is jaw-droppingly surprising is just how low both charities score on great customer service. But they are not alone – the fact is that every other charity they looked at also scores poorly in this area. Seven other radar charts are posted here (including Friends of The Earth, NSPCC, RSPCA, The Royal British Legion, The British Heart Foundation, Save the Children and Oxfam).

When asked about how engaging these brands were, the results were as shocking. Cancer Research UK was best with 12% of those surveyed describing the brand as engaging. The majority scored in single figures.

And it doesn't take a genius to understand why. Brand guidelines are almost always about the charity. Phrases such as we are brave, we are outraged, weare effective, we are honest and we are just dominate these booklets. And far too often, brand policing is solely about ensuring these sentiments are included in copy.

What this process does is suppress the focus on generating engagement with donors. A hand typed and signed letter on poor quality stock that talks about what the donor has achieved is rarely going to appear in a set of brand guidelines, but in comparison with a branded corporate style mailing, I know which pack is going to raise most money AND bring the donor closer to the charity. And it is only through reducing the distance between the charity and the donor that we are going to engender real understanding and solidarity.

The days of the self-congratulatory brand are over. We must acknowledge that our brands live solely in the minds of our supporters. Research shows that the majority of people still trust and regard most charities highly. The role of any brand strategy should be to tackle key weaknesses and that includes managing the brand experience as well as influencing brand understanding and values. By doing so, we will take a huge leap forward in managing the ongoing problem of dis-engagement and the accompanying attrition that afflicts so many charities.

My recommendation is we do this by answering the needs of donors. If you haven't seen my posts on donor needs, I'd recommend you look at this.

By engaging and serving those who support us, attrition is being tackled and significant additional funds are being generated – even in times of recession.

Finally, if this has got you thinking, I'd recommend that you read a recent post from Aline Reed on her blog, Bluefrog Creative where she shares some of her thoughts on brands that generate feelings of love.

Tags In

Related Posts

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

Hi,

Many thanks. This is really useful blog post.

As you can imagine, we at the YMCA were a bit surprised that we weren’t placed within the top 100 on the Charity Brand Index ’09, but on investigation found that we weren’t actually included in the survey at all.

150 charities were selected for the survey’s long-list, based on voluntary income size. Although some charities with federated structures made the long-list, the voluntary income measure meant that many, including ourselves, didn’t feature.

We’re now working with the researchers to ensure that lessons can be learnt from the ’09 Index inclusion criteria and rectified for future surveys.

Best wishes

Simon Badman

Head of Movement Communications

YMCA England

Nice blog!I liked the comparison way you have explained.There are several good points which we need to note them and follow them!

dental