What's wrong with charity advertising?

Howard Gossage is my favourite Mad Man. If I have an advertising hero, it's probably him.

Howard didn't particularly enjoy coming up with ways to sell more cars and airline tickets, he was just rather good at it. What interested him most was making the world a better place.

So when David Brower of the Sierra Club asked him to help prevent the Grand Canyon being flooded through the building of the Glen Canyon dam, you'd have thought Howard's response would be an automatic yes.

But it wasn't.

David asked Howard's agency, Wiener and Gossage, to lay out an open letter he had written to US Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall. It was his last ditch attempt to try to stop the construction going ahead.

Howard read the letter and concluded that it was over elaborate.

To use his own phrase, he thought David was "putting raisins in the matzos" by going into too much technical detail.

In his opinion, this was the same mistake that far too many charities and cause-related advertising made. The ad talked at its audience and in doing so alienated the people who were most likely to help.

As Gossage explained...

" When they [The Sierra Club] came to us for counsel I happened to mention this to them and said, 'What you've got to do is give people recourse. You've got to give them something they can do so they don't feel guilty and, therefore hate you for making them feel guilty'."

Brower wasn't persuaded, so a test was agreed. One million editions of the New York Times carried his open letter ad and one million carried Gossage's ad.

I haven't got the final results, but Gossage's ad (below) outperformed Bower's ad "enormously" (you can find a readable version of the ad here).

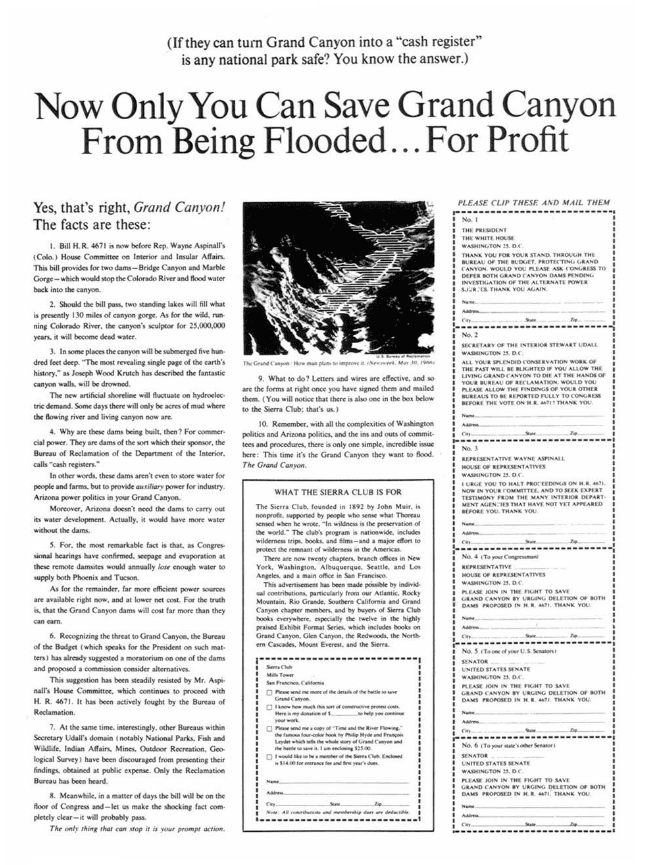

As you'll see from the number of coupons, Gossage's aim was to drive response. Each carried a message that could be sent to the US President, the Secretary of the Interior, the Head of the Interior Committee of the House of Representatives, the reader's Congressman and the reader's two Senators.

As copywriter Jerry Mander admitted, it was the coupons that made the difference...

"Gossage did the important, brilliant thing with those multiple coupons. That had never been done before. They were very, very important because in those days people used coupons; they were their internet."

Brower's original target, Secretary Udall, sums up the impact of the campaign rather neatly...

"That was really a stroke of genius. Of course he knew how to put the heat on you. If you were in my position you had to react."

As a result, support for the Sierra Club doubled from 39,000 to 78,000 and the bill that would authorise the construction of the dam was defeated.

It was the interactive nature of Howard's approach that worked. Rather than lecture, he wanted readers to participate in the ad. This created a connection that meant the brand and message were much more likely to be remembered.

It was an approach that made him different.

He believed that too many agencies suffered from a lack of both creativity and information. Instead they relied on repetition of the same message in the hope that it would finally break through to consumers.

It sounds like much of the charity advertising that we see today – campaigns are praised because the ads look alike and say the same thing.

But when you think about it, this approach is akin to admitting defeat.

We've decided that the only way someone is going to take in our message is if it is constantly paraded in front of their eyes (or ears). That might be acceptable if we're selling something as ordinary as baked beans, but when we are fighting global poverty, tackling climate change or even searching for a cure for cancer is it the best that we can do?

Gossage summed up the problem quite neatly when he said....

"The real fact of the matter is that nobody reads ads. People read what interests them, and sometimes it's an ad."

And that's the point. We need to focus on what interests our donors – not on telling them what we want them to think.

That was exactly what Gossage did with his ad. He gave everyone the chance to protect something that they valued. As a result, the Grand Canyon is still an incredible place for us all to enjoy.

It's a rather amazing story, but it doesn't end there.

You might have thought that after this success, the trustees of the SIerra Club would have been incredibly happy.

You'd be wrong.

They weren't sure that they actually wanted all the publicity and controvercy stirred up by Gossage's campaign.

David Brower disagreed with them. The result was his resignation.

Brower's next job was based in Gossage's office where he set up a new environmental pressure group. After a little debate, a name was agreed - Friends of The Earth.

Hat tip to @HayesThompson for recommending Changing The World Is The Only Fit Work For A Grown Man

Tags In

Related Posts

3 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

Mark… Thank you for bringing back a piece of Howard Gossage’s brilliance. I’ve had the “nobody reads ads — they read what interests them” quote in my show for years, and yet had never actually seen any of Gossage’s work. Your analysis is extremely helpful, too; so thanks times 2. The odd (frustrating? paradoxical? daft?) thing is, the environmental watchdogs still do things the wrong way. Currently, the Grand Canyon is threatened with uranium mining on the rim (it’s always something). A couple of years ago a large US environmental nonprofit had me write a case against that threat. Which I did: on fire with emotional triggers like anger and “loss aversion.” (As Gossage’s ad was.) Did they accept my case for support? No, they did not. They DEBATED my case and then went a different, less fiery direction they were more comfortable with. Today, the threat of uranium mining at the Grand Canyon persists. As you point out, it’s NOT about what the organization responds to, it’s about what the audience responds to. And audiences respond to emotional triggers and “give me a way to express my outrage.” In my view, the environmental movement, ironically, SLOWS the saving of the planet because it prefers to debate the science than to stir the souls of those who will suffer the consequences. Once our planet is fully warmed, then our science-based charities can smugly say, “See, I told you.” They will have kept us safe, though, from emotional triggers.

Mark, after seeing Tom’s post here mine seems trivial 🙂 But I read and enjoyed your post and especially enjoyed seeing the Grand Canyon piece. It reminded me of the article we were referred to by The Agitator on Ed McCabe in The New York Times, and how emotional triggers (and the right triggers to the right audience) rule the day. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/25/automobiles/real-mad-men-pitched-safety-to-sell-volvos.html?pagewanted=all

Hi Mark, I’m about two thirds of the way through the book and enjoying it immensley. I love the irreverant genius of pink air, shirtkerchiefs and the paper plane competition.

I’ve been trying to think of any charity campaigns that used similar techniques in recent years and am struggling. The closest I came to for irreverance was Movember…

I’d love to be brave (and creative) enough to come up with a fantastic one ad, one publication campaign like he used to do and generate such a fab response from it.

Can it still be done in this day and age and in this fragmented media market? I’d love to have a go!