So what have fundraisers been doing over the last 30 years?

A rather interesting paper has just been published by CGAP and CMPO looking at three decades of charitable giving in the UK.

It's based on a detailed analysis on the main trends in giving that uses the government's Living Costs and Food Survey (which used to be called the Family Expenditure Survey – FES).

The last thirty years have been a period of massive social, technological, political and economic change. And by taking a long-term look back in time we should be better placed to make plans for the current turbulent era and those yet to come.

The full paper (all 64 pages) can be downloaded here, but for those of you too busy to read it yourself, here are a few points that I think are worth highlighting:

The Millennium marked the end of a decline in the proportion of households giving to charity

Back in 1978, the number of households that gave (during a two-week survey period) to charity stood at 32%. It had fallen to 25% by 1999. Over the first eight years of the current decade it averaged at over 28%.

To my mind, that bounce back matches the explosion in face-to-face recruitment and is representative of all those young donors finding their way on to our databases.

Donations have increased

Donors are now giving almost three times as much as they did in 1978. But the rise in giving over the last twenty years only reflects the growth in GDP.

As a share of total spending, households give just 0.4% – the same as they did in 1988.

All the new charities that have been set up, the new fundraising techniques that have been introduced, the growth in regular giving (up from 36% in 1983 to 63% in 2008) and the impact of the web haven't had that much impact on how much people actually give.

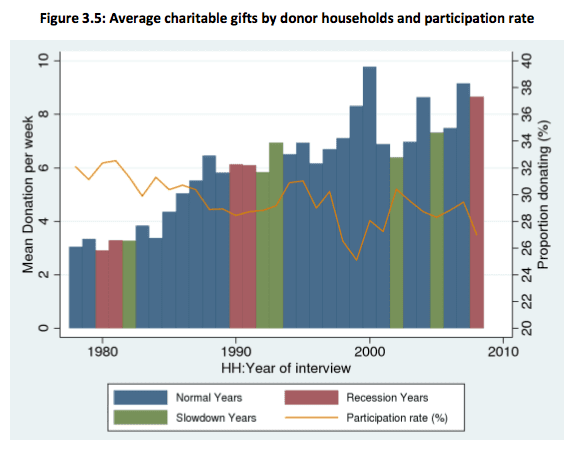

Giving is largely recession-proof

This is something that a number of us who have lived through economic downturns have been highlighting for some time. It's good to see that the statistics support our opinion. As you'll see from this chart, even during the difficult times (marked in red and green), giving has remained strong:

I've posted before that recruitment and subsequent development of new donors can get rather tough when money is tight. Some analysis that I've seen has shown that more donors are just giving a single gift to a charity and simply not responding to subsequent appeals. I'm also hearing of some frightening rates of attrition regarding street fundraising.

And when I look to the future, even with these statistics in mind, I have some real concerns about what will happen over the next twelve months. The number of people who look likely to lose their jobs (particularly older women employed in the public sector) worries me and I will be amazed if we don't see an even more pronounced effect on recruitment. I just hope, that as in the past, our loyal donors will make up the shortfall. Whether they do is probably down to the actions that we take now. But more on that later.

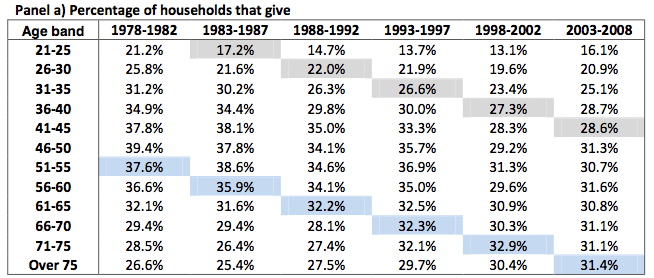

Older donors are becoming even more important

The over 65s now account for 35% of all donations, compared to just 25% in 1978.

One area of particular interest that the report uncovers is the giving behaviour of baby boomers (the youngest tranche of this demographic group is highlighted in grey in the table) whom we first observe when they were in their early twenties and then track right through to their forties. As you'll see, participation grows as they age. That to me is rather good news. A number of people have questioned whether baby boomers will be as generous as their parents and grandparents. The trend indicates that they are (for more on this, please take a few minutes to read the comments to this post).

Affluent donors are giving more

The richest 10% of households now account for 22% of total given (up from 16% in 1978). From 2003 to 2008, the top 50% of households (ranked by donation size) accounted for 92% of all giving. It should be noted that the largest donation observed in the 30 years of data is only £1,500 so it seems very likely that many high-value donors haven't found their way onto the survey. If they were included, the impact of the rich would be even more pronounced.

So what does this mean for those of us fundraising today?

First off, I think we can draw some comfort from the evidence that donors keep giving at times of economic hardship. Though the current recession is particularly tough, I'm confident most donors will remain true to form.

However, qualitative research undertaken by Bluefrog shows that when money becomes tight, donors are likely to focus their giving on favoured causes and organisations.

As a result, charities must concentrate on giving donors what they want – a real understanding of what their giving has achieved and a means of becoming part of the charity rather than just a a source of funds.

This is important for donors of all ages. An ongoing worry of mine is the possible impact a poor relationship might have on donors who are early in their giving lives. A large number of young people recruited on the street are currently cancelling their regular gifts shortly after sign-up. The response of many charities seems to be little more than hoping for the best and expecting the recruitment agency to replace the lost donors as part of a guarantee. Of course, this approach might be effective in the short-term, but what is the long-term impact on how that donor sees the charity when they enter the prime charitable stage of their lives?

Charities should also look at how they treat mid-value donors (those who give between £100 and £5,000). At Bluefrog we've seen that donors in this range respond best to charities who drop the mass marketing approach and concentrate on adding value through increasing relevence and personalisation. The result is a significant increase in income.

Finally, a robust win-back strategy should be developed for donors who lapse. If donors are lost, it doesn't have to be for ever. But winning back should not simply be handed over to a telephone agency. A real relationship is based on hearts and minds, not just repeatedly asking until someone says yes just so they can put down the phone.

Tags In

Related Posts

3 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

Thanks Mark – this is fascinating, and encouraging! I have long thought that our obsession with the death of Dorothy Donor is over-stated as her children – the baby boomers – will eventually step up to the plate.

However, the same research appears to have been interpreted differently by the Guardian (http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2011/feb/15/big-society-decline-in-charity-donations?), where they quote the author of the report, Professor Smith, as saying:

“But having dug into the data, Smith is less sanguine. “Giving is not something, like longsightedness, which besets us all with age; rather, it seems that those born in earlier generations seem more inclined to give more at every stage of life,” she says.”

I read that as the baby boomers, and generation X below, will in fact NOT go on to give in the same way as the Dorothy?

Thank you Mark for posting this thought-provoking piece. I agree with most points you are making and with the insights expressed in Smith’s statement. Personally I think if a charity started to act on some of the issues you are raising re: attrition of new donors they would be streets ahead of others.

As some one who works in the Christian sector I think that one factor that might play an important role in Dorothy donor’s giving is that fact that she is religious – in the sense that she has probably been taught as a child about generosity at church and if she attended church even ocassionally later on in life she would have had opportunities to reflect on issues of generosity, selfishness, putting others first, caring for the poor etc. I don’t think that churches are the only places that teach such values, they are taught in families and other places in society too… But, my point is that as our socciety has become more fragmented (familis too), values such as selfishness and consumerism are increasing replacing selflessnes or sacrificial generosity. We are encouraged to see ourselves as consumers and approach charitable giving with a consumers perspective…

I wonder whether charities are struggling to engage with younger donors because they are dealing with people whose values are different from Dorothy’s. To cut this rummling short my question is: Does this research say anything about how values/ beliefs impact giving?

Are the mor sophisticated fundraising techniques we are using today doomed to produced short term results (people sign for a few months, get bored and stop giving) when used in a society where there is increased indifference and selfishness? I don’t want to take the moral higher ground here but I am wondering about the role that charities can play to promote generosity and other positive values in society… and see Gen Xers and others give more as a result.

Hi Ed, Steve and Redina

Thanks for reading and commenting – and yep, I’ve obviously been sloppy here in my writing and references and need to explain my point in a little more detail.

In the post, I featured just one of the panels from Table 4.4 that demonstrates changes in patterns of giving over the thirty years of the survey. I used this because the grey highlighting was a simple way to illustrate that boomers (in this case the lowest age cohort) were giving in growing numbers as they aged (albeit with a level of volatility). This obviously isn’t the whole story and I can see how I have confused people.

So, first let’s look at generosity amongst those who give.

If you look at Figure 3.3 in the New State of Donation paper, you’ll see that amongst givers, donations as a percentage of household expenditure are increasing (from less than 1% in 1978 to about 1.7% in 2008). Incidentally, the chart also shows a small increase in giving amongst the whole population.

Boomers demonstrate the same pattern. If you take Panel C in Table 4.4, you’ll find figures that illustrate donations as a percentage of total spending amongst givers broken down by age cohort.

If you look at what those aged 46 – 65 were giving in 1978-1982, you’ll see that the average of the 4 cohorts is 0.875% of total spending. In 2003-2008, that same age group (the boomers) is now giving 1.025%. To me, that represents a growth in generosity.

But as Professor Smith and the figures in Panel A demonstrate, the percentage of boomers giving is now less than demonstrated by the same age cohorts in the years 1978-1982.

I think two points need to be made here. One is of definition. The FES and LCFS Surveys used by the researchers include church collections in the measure of charitable giving. We’ve seen a sharp decline in the level of church attendance over the last thirty years – from 11% of the population in 1980 to 6% in 2010 (http://www.whychurch.org.uk/trends.php).

I’d have thought that the loss of such a large number of weekly ‘donations’ as a result of this decrease may well have had an impact on the percentage of households ‘donating’. If we remove those who only gave via church, perhaps the numbers giving to charity in a modern sense may be similar – or perhaps even higher?

It is also interesting to note that the average age of a church attendee back in 1980 was 37, much younger than it is today. Perhaps that gives us the bulge in the number of middle aged households giving at this same time.

The second relates to actual numbers. Back in 1980, there were only 2.6 million people aged 75-84. Today there are 3.5 million. In another thirty years time there are expected to be over 6 million people in this age cohort (including me!).

It may well be that this older cohort are currently keeping donation levels up, but even if a smaller percentage of them give in future, the actual number of people giving will be much larger.

I think the aging population will be good for charities. As the number of people in their ‘giving age’ looks set to grow so should donations. There is obviously a discussion about pensions, investments and house prices to be had here but perhaps that’s for another blog post.

To my mind, people don’t really reach their ‘giving age’ until well into middle-age. And, in my opinion, whether someone gives or not is less related to post war experiences and more about becoming emotionally attuned to the needs of those outside one’s own immediate circle of friends and family.

I’ve posted before on the psychology of giving and this post gives a little direction on the reason behind my thinking.

https://queerideas.co.uk/my_weblog/2010/12/why-do-younger-people-seem-to-ignore-your-appeals.html

But at the end of the day we are all making projections on patterns of giving and interpretation of results.

These are mine and I am more than happy to be convinced I’m wrong. I’d particularly like to have a look at some of Steve’s research into boomers. It could well change my mind.

Thanks again

Mark