Why I love branding

There was a cracking post from Jeff Brooks on Future Fundraising Now last week. It tells the story of how two senior marketing people at General Motors came up with the almost unbelievable idea (now reversed) of banning the word Chevy when talking about Chevrolet cars.

He included part of the memo that announced the plan…

"When you look at the most recognized brands throughout the world, such as Coke or Apple for instance, one of the things they all focus on is the consistency of their branding…. The more consistent a brand becomes, the more prominent and recognizable it is with the consumer. This is a big opportunity for us moving forward…. One way to achieve this is with the use of Chevrolet vs. Chevy. We'd ask that whether you're talking to a dealer, reviewing dealer advertising or speaking with friends and family, that you communicate our brand as Chevrolet moving forward.

"We have a proud heritage behind us and a fantastic future ahead of us … speaking to the success of this brand in one consistent manner will ensure Chevrolet becomes even more prominent and recognizable than it already is."

Forgetting for a minute that Coke is an abbreviation of Coca-Cola and that most people who use Apple computers simply describe them as Macs, it's a perfect example of a couple of commercial branding gurus forcing their (mistaken) opinions on a company, its heritage and the people who actually spend their hard earned cash buying and running the cars.

But how does this matter to charities? Jeff sums it up very well…

"In just one way: We are suckers for branding and marketing gurus from the commercial world. I'll bet virtually any nonprofit who could afford them would hire either of the Chevy geniuses in a heartbeat …

"And then they would proceed to put their brains to work doing to their nonprofit employer what they tried to do to Chevy (I mean Chevrolet).

"Because that's what they do.

"They do it in their own world. They'll do it even worse in ours, as they never quite seem to grasp that we aren't selling junk, but motivating people to give."

As you might imagine, I've more than a little sympathy for Jeff's view. I've struggled with communications people and above the line agencies telling me what I have to say to donors and how I have to say it.

And I think that the key problem that lies at the heart of the commercialisation of charity branding is the attitude that people from the for-profit sector bring with them.

The brands that they create for the products and services they sell normally have a guarantee at their core. It says we are great because you can dependon our product to wash your clothes whiter, make you better looking, appear cooler, give you more energy, make you thinner or whatever the consumer hands over their money for.

And that doesn't transfer to charities. A charity actually has to say something completely different.

They have to say we depend on you.

That's why I think the word branding is so dangerous for charities. It completely misses the point. A charity shouldn't be looking to build a case for support on why it is so great. It should concentrate on Wally Olins' preferred definition of branding – seduction. As he explains in On Brand…

"We should remain quite clear that what marketing, branding and all the rest of it is about is persuading, seducing and attempting to manipulate people into buying products and services."

And how does he see this as relating to charities?

"..having 87 charities with 87 names, 87 offices, 87 sets of overheads however miniscule, 87 sets of promotional material mostly of a banal nature (how many plastic pens can you use use?), all competing with each other, is not only messy, but more important it's highly wasteful and counter-productive. And it doesn't help children in need. How can members of the general public make sense of this? How can we distinguish between one children's charity and another? How can we have the faintest idea what happens to our money? How can a charity, having once captured our interest, sustain it so that we remain regular, committed and brand loyal? For the most part, the answer to all this is that charities don't deal with these issues in a professional way…""…Over the first quarter of the twenty-first century branding will become a powerful force in charities. Major charities will capture our concern and interest and our money. They will draw us into Friendship Associations and try to tell us how our particular donations are used. They will become skilled at merchandising their clothing and memorabilia. They will memorialise us.They will create headlines out of heartbreaking causes which will engage us and persuade us to commit money and sometimes time to their cause. They will link us to individual cases, personalise it all. This kind of commitment to charities will enable us to feel better about ourselves."

Friendship Associations? Telling us how our particular donations are used? Memorialising us? Engaging us? Linking us to individual cases? Personalising? Feeling better about ourselves as donors?

If this is what branding is really about, then I love it.

Which is why I find it so frustrating that so many re-brands are simply about the identity, the latest list of values, the logo, the use of photographs and the use of language. In short, the imposition of controls that benefit no one but those who create them.

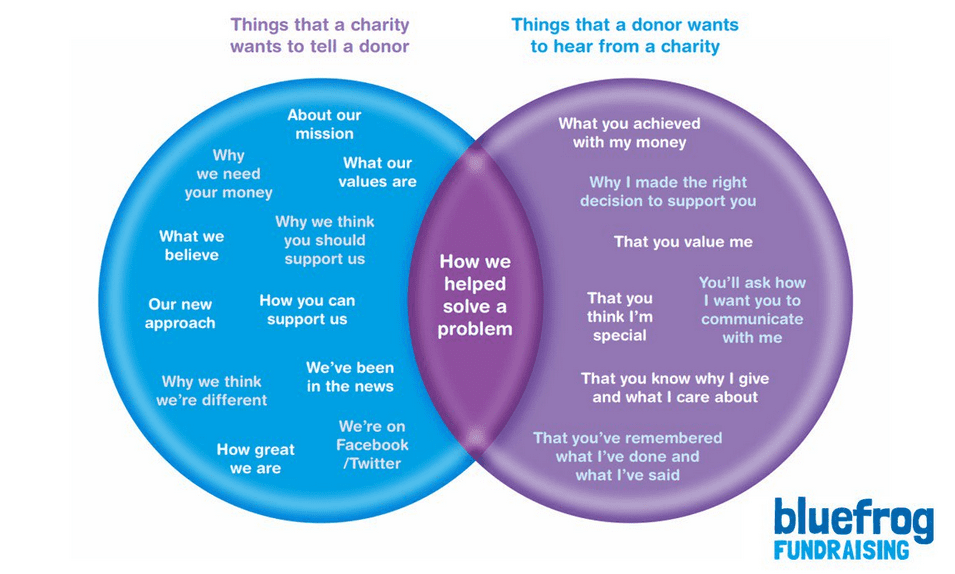

The critical factor in any brand mix for a charity is the behavior of the individual members of staff in their day to day relations with members of the public – be it face to face, on the telephone or through printed or digital media.

If they focus on showing donors how important they are, what they have helped achieve as individuals and how the charity depends on them to help tackle the causes that donors care about we will see the development of brands that don't just matter, but actually become central to the success of the charities that adopt them.

And after all that, here's something that might not exist if the guys from Chevrolet, who don't seem to understand what branding means, were around forty years ago.

Tags In

Related Posts

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

Wonderful post. Your brand isn’t about your logo, it’s not even about what you (your board and your gurus) want to say it’s about, it’s what your donors think, feel and say it is. Posted something similar myself recently citing nestle and BP as examples http://z6.co.uk/g838rd

I agree almost 100% Mark but I feel you’ve missed a few key points (not intentionally, I’m sure).

Firstly, there are more stakeholders than just donors. I appreciate that for a fundraiser donors are the most important audience but service beneficiaries, staff, volunteers, campaigners, key influencers and donors are all inextricably linked in terms of a charity’s success.

So, when we talk about it not mattering what just the SMT or Trustees think about the brand, I think that’s absolutely true. The sum total of stakeholder audiences’ opinions are what counts as these will drive (or not) the desired action. We just need to remember that influence over a charity’s success extends more widely than from just donors.

Secondly, in my experience, logos and identities are a necessary means to an end. That end being to build awareness of the charity amongst all it’s constituent audiences. That said, if the actions of the charity (as you describe above) don’t reinforce what the charity stands for and the benefits it brings, then the brand has no credibility. Consequently, encouraging donors to give, people to volunteer etc becomes that much harder.

I talk to clients in terms of the following reaction from a target audience (ie; potential donors, volunteers etc):

– brand awareness = “I’ve heard of you”

– brand credibility = “You have sufficient credibility in my eyes at what you do to have the right to ask me for money / time…”

So yes, the stakeholder audiences (plural) have the only opinions that count. Yes, you must start somewhere with building their awareness of what you do by using the right and appropriate brand tools. And yes, your actions must consistently back up the claims you made with those branding tools if you want any stakeholder audience to actually engage with your cause.

The last part is the hard part, of course. And, not all commercially-experienced branding people miss the point… Innocent Drinks, Body Shop, Apple….