40 years on: Why wouldn't you wear a Band Aid T-shirt?

The reception of the re-release of Do They Know It’s Christmas? as a super-mix to mark its 40th anniversary highlights some shifting attitudes toward global charities that need to be understood by fundraisers who work for INGOs. Unlike its past successes, the single failed to make the top 40 in its first week. Ed Sheeran distanced himself from the re-mix, citing that his “understanding of the narrative…has changed”, whilst musician Fuse ODG openly criticised the song as outdated and harmful. In a Guardian article, he shared how his stance has sparked reflection, with some donors questioning traditional narratives surrounding global aid – one man told him that his comments had “really made him think differently about Band Aid”.

This reflects a broader change in how donors in wealthier nations now view INGOs. In the conversations we have with donors as part of our research programme at Bluefrog, we have seen scepticism toward traditional development charities evolve over the years. But it has become much more pronounced since the Haiti safeguarding scandal of 2018 and the criticism of Comic Relief for perpetuating "white saviourism," by David Lammy in 2019.

Ethical Paralysis: The New Challenge for INGOs

Increasingly, younger donors report that they see supporting large INGOs as risky or even, problematic. A young woman in one of our studies summed up this feeling by describing it as a sort of “ethical paralysis” that stopped her giving. Unsure if her donations were doing the “right thing” it became easier and more comfortable not to give rather than take the risk that their donations may not be put to good use - and may actively harm people instead.

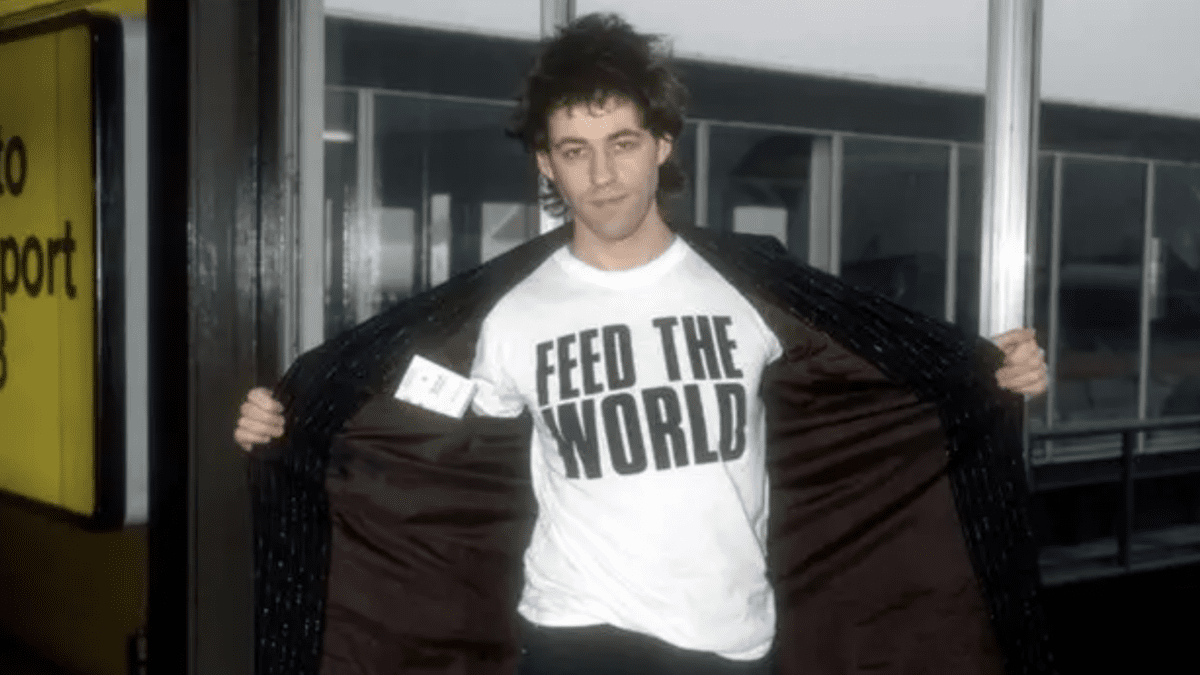

Charity T-shirts, for example, once worn as symbols of pride – like the iconic Feed The World shirts – now carry a more complicated meaning for many younger donors. What was once a badge of honour is now, for some, a mark of controversy, with wearing one potentially sparking negative associations.

In contrast, older donors – the original Band Aid generation – may still have those vintage T-shirts as prized possessions. While they might have outgrown them with the passage of time, their loyalty to the wider cause remains strong, and many are giving more generously than ever. However, for many of them, perspectives on aid have shifted. The way they view global charities, and their work has evolved, reflecting broader changes in attitudes and expectations.

A Geopolitical Lens: The Changing Perspective of Older Donors

For older donors, aid in the 1980s and 1990s was primarily about delivering an integrated programme of tangible support – providing essentials like tools, water and food, education and medical care. Today, however, many of the most committed donors’ approach global poverty with a more nuanced and realistic perspective. Their views are shaped by complex geopolitical factors such as international trade imbalances, the escalating impacts of climate change, ongoing conflicts, and the influence of global superpowers.

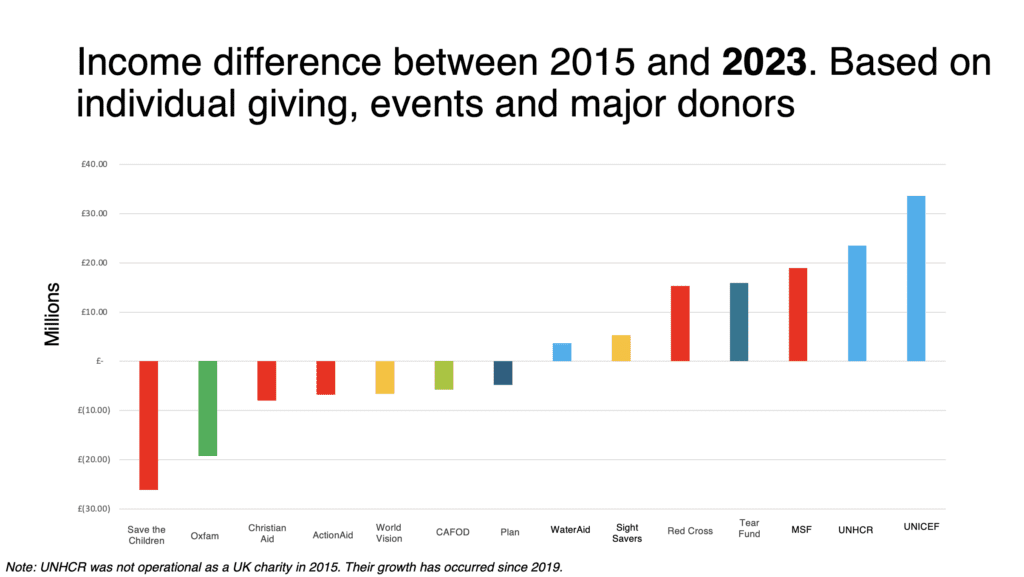

The big, traditional generalist INGOs are increasingly seen as ineffective against this multi-faceted threat, whereas specialised organisations such as MSF or WaterAid are viewed as cutting through this complexity, offering focused impact in specific areas of work. UN agencies like UNHCR and the World Food Programme have also gained favour for their perceived reach and strength which comes with a greater sense that they are able to address systemic issues like war and climate change on a multilateral scale.

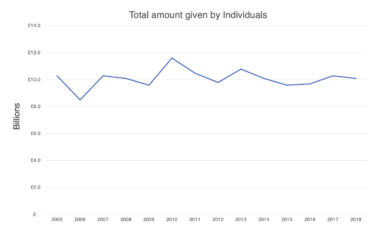

These changes are apparent in the income trends of our largest INGOs. The attached chart comparing figures from 2017 to 2023 reveals significant declines for the generalists, whilst specialist charities and UN agencies have seen growth (these numbers are taken from annual reports and are not always directly comparable). Micro-charities working directly in developing countries are also gaining traction, appealing to donors who value direct impact and transparency.

But we need to dig deeper into these trends to see who is giving – and who isn’t – if we are to be more effective at engaging more support. At Bluefrog, we simplify this analysis by categorising INGO supporters into three broad groups:

- Sentinels

Sentinels are older, wealthy, and highly educated individuals. They are the Band Aid generation who have done well and have become deeply engaged with global issues – particularly those that impact on the most vulnerable communities. Their understanding of the world is shaped by sources like broadsheet newspapers, whether printed or online, and current affairs programmes such as Channel 4 News and Newsnight. These donors usually give at a mid to high-value level, providing the lion’s share of support for many charities. They actively seek out organisations that address specific problems or work, ensuring their contributions align with their priorities and values.

- Casual Contributors

Casual Contributors are donors who, while often maintaining a direct debit to support INGOs, primarily engage during moments of high visibility, such as emergencies. Their giving is reactive, driven by urgent needs rather than ongoing involvement. Whilst they provide essential support in critical times, their engagement remains limited outside of these moments.

- Humble and Holy

Humble and Holy donors are motivated by their religious beliefs and often choose to give through faith-based organisations such as Tearfund, Islamic Relief, or their local churches and mosques. This group is typically well-informed, drawing insights from familial and community connections, which are often enhanced by the accessibility of the internet as a means of connection and a way to distribute funds. These direct links to projects empower them to give with confidence, bypassing the need for larger INGOs. Interestingly, younger donors are particularly active within this group, finding the transparency and direct impact of faith-based giving a strong motivator for their support.

Proving Impact: Why Younger Donors Won’t Settle for Less

So why aren’t younger people engaging with traditional INGOs more widely? The answer is straightforward: these organisations aren’t meeting their needs. In many respects, younger donors are remarkably similar to their parents and grandparents – they still value transparency, accountability, and clear evidence of impact. However, they are far less forgiving. And that extends beyond how charities treat them – they are much more reluctant to align with organisations associated with outdated practices or controversy.

This presents a significant challenge for fundraisers at the larger INGOs, particularly those still reliant on face-to-face acquisition strategies that dominated recruitment in the early 2000s. These organisations are struggling to keep their regular giving files topped up because the younger donors that this approach depends on simply aren’t engaging in the same way as their parents once did. To compound the issue, they’re also failing to attract older people from the Band Aid generation, who might otherwise boost their ranks of supporters.

The reality is that large INGOs can still rely on older donors for the short to medium term. This loyal group will continue to give, with many leaving legacies that will sustain these organisations for now and in the next decade or so. But as time inevitably moves on, this supporter base will dwindle. Without forging meaningful connections with younger generations - as Band Aid did so effectively with teenagers and twenty-somethings in the 1980s – the future for the big, non-UN INGOs looks increasingly uncertain.

But here’s the rub. Younger donors don’t require anything outlandishly innovative to engage them – as long as they have enough available cash to give to charities. Some of the gimmicky efforts we see today, such as branded Christmas tree decorations designed to encourage a shallow type of hybrid giving, completely miss the mark. These ideas fail to address what truly matters to younger donors - transparency, accountability, and meaningful impact.

But it’s no secret that money is tight for many younger donors. Student loans, high rents, and the relentless rise in the cost of living severely limit what they can afford to give. However, we need to remember that effective fundraising isn’t just about immediate returns. Despite the criticism directed at Bob Geldof and Midge Ure, their efforts in the mid-80s sparked a profound cultural shift, inspiring a generation to see themselves as part of a global community. That legacy continues to benefit INGOs, large and small, by creating a connection that still holds relevance decades later. In this way, Band Aid has raised hundreds of millions more than that generated by the sale of the various iterations of the single and concert tickets.

Today, however, much of what large INGOs offer fails to resonate with younger audiences. Speak with them, and they’ll recount stories that have shaped their views -stories of perceived failures, where organisations like Oxfam, despite significant evidence of positive impact, are seen as not standing by the weak and oppressed when it mattered most. These narratives cut deeply, leaving lasting scars on the reputations of the whole aid sector. Yet, the organisations in question have done little to effectively counter these perceptions. In our discussions with donors, these concerns arise time and again, continuing to shape how people view and engage with these charities today.

A Local Lens on Global Issues

You’ll also find that younger people’s charitable concerns often lean towards domestic issues, even when their focus is global challenges. Whether it’s fighting injustice or addressing climate change, their attention tends to be on actions they can take locally rather than internationally. This shift offers a critical insight into how charities should approach and engage them.

Connection is key. Younger donors value personal interactions, clear evidence of the impact their support has achieved, and a deeper understanding of the root causes of the issues they care about. In many respects, their priorities align with those of older donors. However, the key difference lies in their expectations and their far lower tolerance for poor treatment and poor behaviour.

Older donors are often content to give and trust that their contributions will make a difference. Younger donors, by contrast, demand transparency and accountability. They want to know exactly where their money is going and what impact it is having. For them, vague assurances aren’t enough - they need confidence in their actions, especially in light of ongoing criticisms of the larger INGOs.

Adapting to these expectations is not just essential for building lasting connections with the next generation of supporters - it’s also an opportunity to strengthen relationships with older donors. Great stewardship and meeting donor needs, after all, is a win-win for everyone.

The Path Forward

In research, we often like to ask donors: how would you feel wearing a specific charity’s t-shirt? Would it create a sense of belonging? Or would it leave them feeling a little uneasy. Band Aid T-shirts were once a massive fashion statement, a symbol of shared purpose and compassion. But today, the story is more complicated, more nuanced.

The way forward lies in creating that sense of belonging and value for donors of all generations. In many ways, charities have had it easy. Baby Boomers and much of Generation X have been content to offer their support with minimal expectations – happy to receive a simple acknowledgement for each gift and a yearly, broad, generalised report about what the charity has achieved.

However, if the big INGOs are serious about engaging millennials, they need to double down on what works. They must move beyond being a vehicle for giving, to becoming a facilitator of a meaningful, shared mission. It’s no longer just about raising funds – it’s about creating a sense of community where every donor feels a valued member of a valued group.

And as I’ve highlighted, this starts with connection. Committed donors, especially younger ones, want to see themselves as integral parts of a movement, working toward tangible and impactful change. Charities need to be clear about how funds are being used and demonstrate the specific outcomes they are achieving. This isn’t just a matter of sending out links to digital reports. it’s about fostering an ongoing conversation that keeps donors engaged, showing them the meaningful role they play in driving impact. And yes, it needs a goal: to make people proud to wear your t-shirt.

And to this end, storytelling is crucial. Donors need to see the faces and hear the voices of the people their contributions are helping. Authentic, personal stories from the ground resonate deeply, building emotional connections that inspire loyalty and trust. For younger donors, these stories should also include insight into the structural causes of the issues they care about – whether it’s climate change, inequality, injustice or systemic poverty – and what’s being done to address them. And remember – above all else, storytelling isn’t just about you telling stories, it’s handing the narrative to your supporters – so they can tell your stories – and make them their own whilst they are doing it!

Feedback loops are another essential element. Charities must go beyond traditional thank-you messages and provide regular updates that demonstrate progress and impact – a practice we call Dynamic Thanking at Bluefrog. By showing donors the results of their solidarity, INGOs can strengthen the emotional bond between supporters and the cause. This approach is especially vital for younger donors, who are driven by a strong sense of agency. They need to see that their contributions matter and are part of a larger, impactful solution.

And of course, effective Dynamic Thanking means personalised engagement is key. Donors should feel recognised for their unique contributions and concerns. This means tailored communications that reflect their giving history, direct interactions through social media, or opportunities to provide input via feedback channels. Such efforts ensure that donors feel heard, valued, and involved - far more than just another faceless participant handing over cash. Personalisation fosters loyalty and strengthens the connection, transforming one-off supporters into long-term advocates for the cause.

To resonate with younger audiences, charities must also adapt their messaging to include a local lens on global issues. By framing global challenges in ways that connect to local actions or impacts, INGOs can bridge the gap between donors' domestic concerns and the broader international context.

And perhaps most importantly, charities must recognise that younger donors are drawn to organisations that reflect their values and are authentically inclusive, again highlighting the voices of those directly affected by their work.

Ultimately, the future of the large INGOs depends on fostering a culture where donors feel like valued members of a collaborative effort to create positive change. By prioritising connection, transparency, and accountability, charities can build the trust and loyalty needed to engage both current and future generations. This isn’t just about keeping up with changes in fashion – it’s about securing the long-term relevance and sustainability of the sector while addressing the immediate challenges of declining income. By embracing these principles, INGOs can ensure they remain impactful in a rapidly evolving world.

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: Learning From the Past

So what should you do if you work for an INGO that is struggling to reverse a decline in income and connect with a younger audience?

Rather than dismissing what Band Aid achieved, take a moment to reflect on its legacy. Recognise how a single, powerful act of connection inspired an entire generation to see themselves as part of a global community.

That sense of collective purpose turned donors into active participants in addressing poverty and injustice, leaving a lasting impact that continues to benefit INGOs today. However, the lukewarm reception of the re-release of Do They Know it’s Christmas? serves as a stark reminder that this connection has frayed, particularly with younger donors.

The challenge for charities now is to reignite that spirit of belonging – not by replicating Band Aid, but by understanding what inspires today’s generation of younger donors. It’s about flatly rejecting transactional techniques and instead creating a culture where all donors, young and old – as I’ve said before – feel like valued members of a valued group – working in a global partnership with people from the global south. Where they are proud, perhaps even desperate, to wear your t-shirt as a symbol of shared purpose.

The big INGOs must focus on building authentic connections and fostering a sense of shared mission to rebuild trust and engagement, as they deal with the unanswered questions from the past. Just as Band Aid made buying a record or a T-shirt feel like a collective act of change, today’s charities must also create a sense of community where every donor understands the importance of their role and the power of their contribution – or just as importantly, their inaction.

What T-Shirt Would you Wear?

Ultimately, the future of the large INGOs lies in fostering a sense of pride and purpose - something as simple yet profound as wearing a Feed The World T-shirt once represented. That T-shirt wasn’t just a piece of clothing. It was a badge of belonging, a declaration of values, and a symbol of collective action.

To engage the next generation of donors, the missions of these INGOs must be something people are proud to wear emblazoned across their chests once again. By giving people a reason to reconnect and come together, by addressing doubts, and reigniting a shared sense of purpose in everyday conversations, INGOs can foster a community of supporters who don’t just give but stand with them with pride.

When donors feel that deep sense of belonging – symbolised by the simple act of wearing a T-shirt - they aren’t just donors – they become an integrated part of the movement for change, allies with their partners in the global south. That’s the type of connection that the world needs now more than ever.

And finally, if you haven’t had a chance to see it yet, here’s the super-mix. It has now moved up to number eight and still might make it to number one.

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?