Points to consider when raising funds during the attack on Ukraine

Few of us will have been unaffected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to forget the harrowing images I’ve seen and the horrific stories I’ve heard. No doubt you, like many others, will have happily lent your support to the many private and public fundraising campaigns initiated to help the people fleeing their homes along with those trying to survive in the cities that are under siege.

The public response has been tremendous. At least three families that I know personally have undertaken their own collections that they will deliver to the Polish border. And I only have to look at some of the results from appeals that Bluefrog has been running to see that the amounts being donated to help the people of Ukraine are dwarfing those raised at the height of pandemic.

At times like this it can be hard to focus on our own day-to-day work and responsibilities, but the needs that we address everyday have not disappeared. That’s probably the reason why I have been asked a number of times over the past few weeks about what charities who aren’t directly helping the people affected by the conflict should do. Should they carry on fundraising or put everything on hold? Will people still want to support other causes?

My advice is the same now as it was at the beginning of the pandemic, if those you work with still need help, you should carry on fundraising.

We know from history that a major crisis like the invasion of Ukraine will focus the minds of those of us with a desire to help. But this goes far beyond the cause at hand. If we look back in time to the Indian Ocean Tsunami that devastated so many lives in 2004, there was some useful analysis undertaken at the time to measure how giving was impacted across the sector.

Within a month of the disaster, the IOF (now the CIOF), was surveying charities to find out what had happened to their fundraising. They found that just 40% of organisations noticed a change, with the division between those who had raised more and those who had raised less being split almost equally.

Move on six months, and the next survey found that 58% of organisations had maintained or increased income with over three-quarters of charities believing that the impact of the Tsunami would have a long-term positive impact on public generosity. Over the next few years, sector income grew from £8.2 billion in 2004/05 to £9.4 billion in 2005/06 to £10.6 billion by 2007/08.

By the end of 2005, further analysis by CAF found that of every £1 donated to the Tsunami, 80 pence was new money and 20 pence was redirected by donors from funds originally intended for other causes.

However, things are different today. We've lived through two years of a pandemic, the economic future looks very worrying and concerns about a wider war in Europe are not far from our thoughts. So what might happen to giving next?

Just as we saw in 2004, I don't think that many people will abandon the causes that they value as a result of the outpouring of support for the people of Ukraine.

One of the consequences of the pandemic is that it caused large numbers of people to re-engage with giving. They saw need directly – in their communities and in the media – and they wanted to do something to help. So they opened up their purses and wallets and gave. This gave them a sense of control in a very worrying time.

But it went further than this. As I've previously explained, during the pandemic, helping became an important way for people to define who they were – and what they believed in. The distinction between 'good' and 'bad' became a key driver influencing our behaviour. We became much more likely to see injustice and be agitated by it. Giving became central to managing our self-esteem. And, as ever, it helped us to deal with the distress that we felt when we saw that people were suffering.

This re-engagement hasn’t simply disappeared now that the pandemic has fallen down the media radar. As I have already reported, donors are continuing to be very generous. Many appeals broke records over Christmas – even compared to those in 2020. The fact is that the pandemic served to magnify the sense that if we are able to help others, we should.

Additionally, there is zero sense that donors feel over-solicited. All of which leads us to conclude that people will keep on giving – as long as they can afford it. However, we also have to factor in an economic squeeze in our planning as this may well cause some donors to reconsider how they balance their own personal charity budgets.

In our discussions with donors, we see that they continue to prioritise giving according to three factors:

- Where need is perceived to be greatest

- What is personally relevant to the donor

- When they believe the charity depends on them

That means for many people, helping refugees will remain front of mind for some time to come. The war in Ukraine will continue to dominate our collective minds moving forward. Things are not going to settle down in a few weeks. Even if Russia pulled their troops out tomorrow, the shocks of this war will be with us for months and years ahead. But we also need to consider the fact that the impact of the war will exacerbate the economic pressure on the most vulnerable in the UK and beyond.

The economic crunch of rising energy and food prices, tax increases and inflation (or possibly even stagflation) are a serious cause for concern (this is worth reading on broader economic consequences of the war).

As a result, the question isn’t really should we fundraise? it’s probably better to ask what should we do now to prepare for what happens next? And there are a number of actions we can all take to ensure we are better placed to navigate the future that lies ahead of us. Here are a few suggestions that may help you when developing your own plans:

- Focus on core donors

Financial crises don't hit uniformly. Many of your donors – particularly those who built up savings over the course of the pandemic – will be cushioned from the worst effects of the economic crunch. So keep an eye on your segmentation and look at how different groups of supporters are responding to your appeals. As a rule of thumb, long-term supporters and mid-value donors are those who are likely to stick with you and perhaps give more. Ensure these groups are aware of any problems that you face and are given an opportunity to plan how they help you. There are also opportunities now to ask for RG upgrades. Amber Nathan, Bluefrog’s Head of Research, reports that this remains a universally popular ideas when she raises it with donors. - New donors

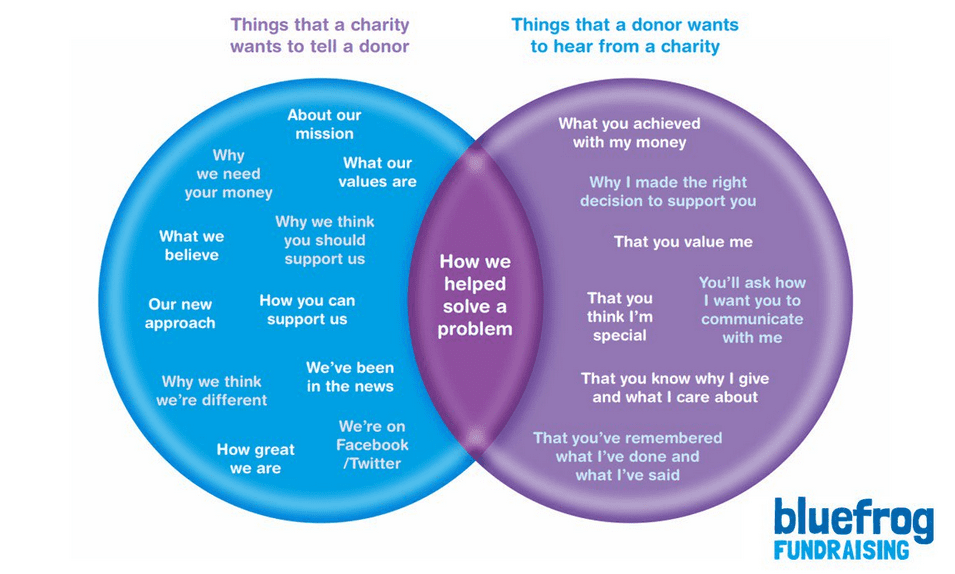

Consider mid-value donors within your recruitment plans. Look at what offers you have that can give people a sense of achievement in tackling the problems that you are dealing with now. - Reaffirm the decision to support you

This is an important time to sharpen up your thanking and reporting back. This has to go beyond a simple email acknowledgement. Recognise what your donors have done and what they are helping you achieve. Demonstrate how much you rely on their support and how important they are to you. And as always, personal beats automated. At the very minimum, write a few personal words (with a pen) on every thank you that you send out. - Consolidation rather than diversification

This is the time to help your donors solve the problems that they care about, not to sell new products or shift your focus on new areas of work that may have little to do with your core competencies. People have moved from one frightening time to another. Giving offers them an opportunity to gain some control. If you have a rebrand in the pipeline, delay it as any further changes in a turbulent time won't necessarily be welcomed. - Maintain relevance

Place your work into context but construct your appeals with sensitivity and care. A few words of recognition of the invasion before getting straight to the point of your appeal is not necessarily going to hit the right note. Instead focus on what your donors most value about your work, now. That could be how you are responding to those most impacted by the economic downturn, which will be of increasing concern for donors as we progress through 2022. And don't forget about Covid either. People have not forgotten the pandemic and are wary of its return. Of course, if your work is directly focused on helping refugees, that should be central to your appeals. - Acknowledge financial insecurity

Your starting point should be to recognise that some people may have re-allocated funds or that they are financially stretched. Treat reactivation programmes with care and consider reducing prompt levels for poorly responding segments. Offer payment holidays or non-financial ways to help. And, of course, ask your donors what they want to do longer term - particularly if they stop giving. We also know from many conversations, that legacy giving is under active consideration for many people.

Whatever you choose to do, that long awaited return to a 'pre-pandemic' approach to fundraising remains a long way off.

Best of luck.

Tags In

Related Posts

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

[…] See how you can earn $27 in 7 minutes! Read here – … by Make Money […]

[…] Raising funds during the Russian invasion of Ukraine […]