Fundraising in 2021 - what might we expect?

The roller coaster that is 2020 isn't even half way through and we've seen huge changes in the fundraising landscape. And that's before we've even started to think about 2021.

At Bluefrog, we've spent a significant amount of time speaking to donors, reviewing secondary research and scenario planning for the next 18 months. And I thought it might be useful to share some of the evidence we are using to help you develop your own plans.

Obviously there is still an element of flux – we don't know what we don't know – but that shouldn't stop us from looking at what factors might influence giving in the immediate future.

There are three areas that I'm going to consider.

- The economy

- Social changes

- Available wealth

1. The economy

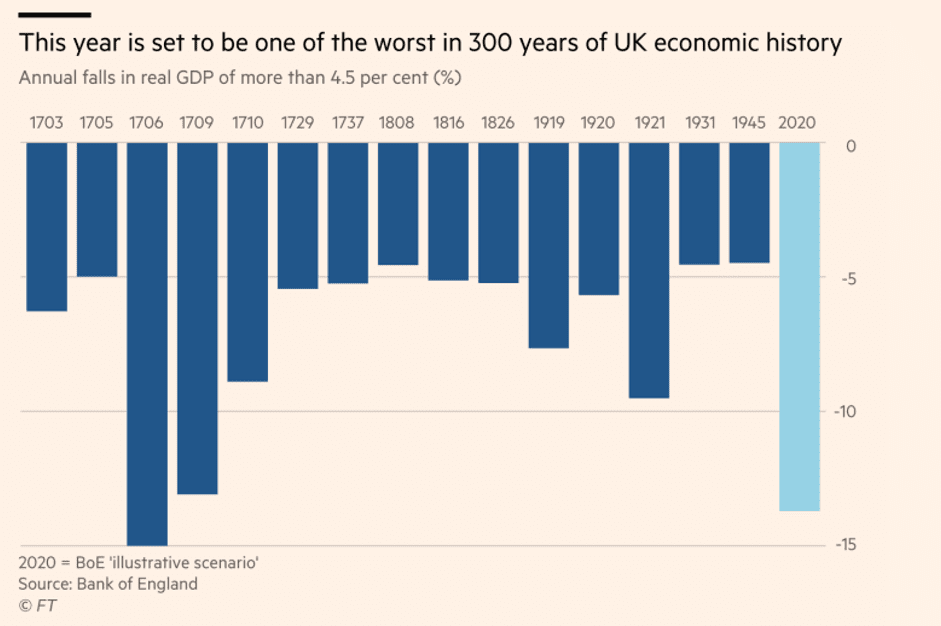

Whichever country you happen to fundraise in, you need to accept that we will be moving into a global recession. The Bank of England has recently released its projections for this year. They demonstrate that we can expect a decline as deep as anything we've seen in 300 years.

The following links will take you to numbers for Australia, USA and Canada.

So what does that mean for fundraising? First off, we need to consider the impact that recessions have on attitudes to giving – and this is where things get interesting.

If we look at what happened during the Great Recession of 2008/09 it's generally accepted that there was a negative impact on giving.

However, as highlighted by Changes to the Giving Landscape, published in 2019 by Indiana University, the recession didn't hit everyone...

"Although the economic shocks associated with the Great Recession greatly influenced U.S. philanthropy, its effects were not felt uniformly by all donors".

The report shows that amongst donors, the percentage of income given to charity remained pretty much the same – pre and post-recession. But more non-donor households emerged following the Great Recession. This brought down the average percent of income given to charity by all Americans.

They also identify that it was mainly households on lower levels of income that were most likely to reduce their giving – or stop altogether.

In the UK, there was also a fall in giving (which seems to sit within the range of variations that have occurred over the last twelve years). Take a look at figures from the 2019 UK Civil Society Almanac, and you'll see voluntary income bounces around, but compared to the growth that we saw in the early 2000s, has remained broadly static.

Digging deeper, I can't find the type of analysis undertaken by Indiana University for the UK. But luckily, Bluefrog undertook a qualitative research study just after the financial crash in 2008 to find out what impact the recession might have. We discovered, that giving intentions were underpinned by a sense of financial security, with over half the people in our study reporting that they would give more than pre-recession (concurrently, a study undertaken by Barclays Bank amongst wealthy donors in the UK came to a similar conclusion).

Amongst the smaller group of donors who felt they had been hit financially, we found the desire to do good did not dry up. These donors reported that though they might cut back on giving they would still give – with a focus on:

- their favourite charities and causes

- organisations helping people who were suffering from the impact of the recession

- organisations that demonstrated that they valued their support

It isn't dissimilar to what happened in the USA. If cash is in short supply and you simply don't have any to give away, you can't give. But if people want to see work that they care about continue – and they have resources – a recession doesn't stop them.

But getting back to 2020, the point we need to accept is that we are not necessarily looking at a simple recession. Rather than a couple of quarters of negative growth, we are facing a crisis. So I'm not sure how much sense it is looking at past recessions in order to make predictions about what might happen next.

To that end, I think we have to go back much further in time. And again, I'm primarily drawing on US data here, but if you take a look at the analysis undertaken in Founders’ Fortunes and Philanthropy: A History of the U.S. Charitable-Contribution Deduction you can start to appreciate that the public response to a crisis is very different to that in a recession.

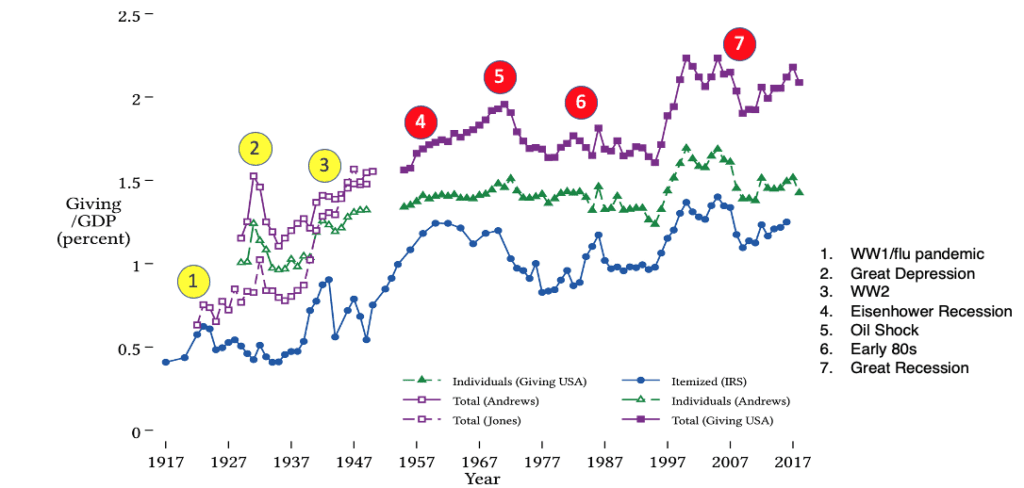

The following chart from the report uses a number of sources to illustrate giving behaviour from just before America entered the First World War up to the present day.

The blue line indicates tax claims on charitable giving so is likely to represent giving from wealthier people, the green line represents giving from individuals and the purple line is total giving.

I've highlighted key events. The recessions are marked in red and the crises are marked in yellow. The first crisis is the First World War (and the Spanish flu pandemic that followed). The second is the Great Depression (1929-1933). And the third is the Second World War.

Rather than initiating a fall in income, there seems to be an increase in giving during these times of international crisis.

Giving was not as high as it is now (in terms of a percentage of GDP) but look at the spikes of generosity at each of the three crisis events – and also note how small the 'bump' is (within a broad dip) from wealthier donors (the blue line) during the time of the Great Depression compared to that from all individuals (the green line).

John Mohan and Karl Wilding also looked at this period in their review of the impact of economic downturns on voluntary giving undertaken in 2009. They highlight that giving to community based organisations such as Community Chest and the United Way peaked in 1931 at $101m before falling to $69m in 1934. They also point out that the tax return data shows a significant drop in giving between 1928 and 1933 from wealthier donors. It does appear that 'normal' people, if they could afford to give, were giving generously at this time.

I'd also highlight a further, potentially relevant point - the founding of the March of Dimes in 1938 to counter another terrible disease, Polio.

In the UK during the First World War, giving also rose dramatically. In his book, Philanthropy and Voluntary Action in the First World War, Peter Grant showed that this generosity came predominantly from everyday, normal people...

"Charitable activity in the war was, especially in many industrial towns and cities, a manifestation of working-class solidarity with many more organisations run by ordinary women and men than by well-to-do matrons. It was easily the most significant charitable cause that had ever been supported in Britain”

And of course, would we have the NHS in Britain if it had not been for the impact of the Second World War?

As I've highlighted in previous posts on why people are giving so generously at this time, this is an emergency – our emergency. And thus, has the hallmarks of a crisis rather than a simple recession.

And just as we have seen from history, it is generating some significant societal change.

2. Social change

In addition to Bluefrog's qualitative findings, there is a significant amount of quantitative research that shows the pandemic and subsequent lockdown has caused a dramatic shift in what we want and what we value as a society.

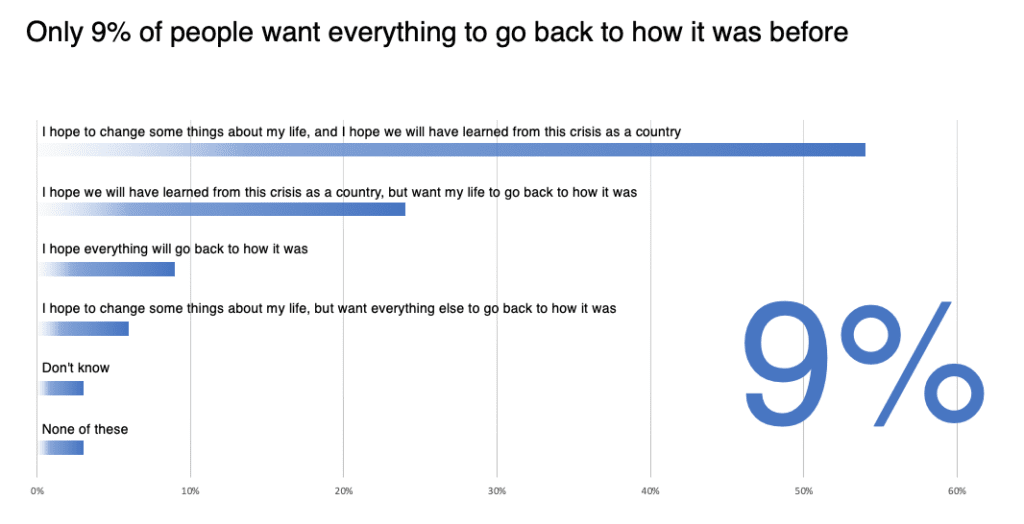

In a national survey, the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission found that just 9% of people want society to go back to how it was before the virus transformed how we are live.

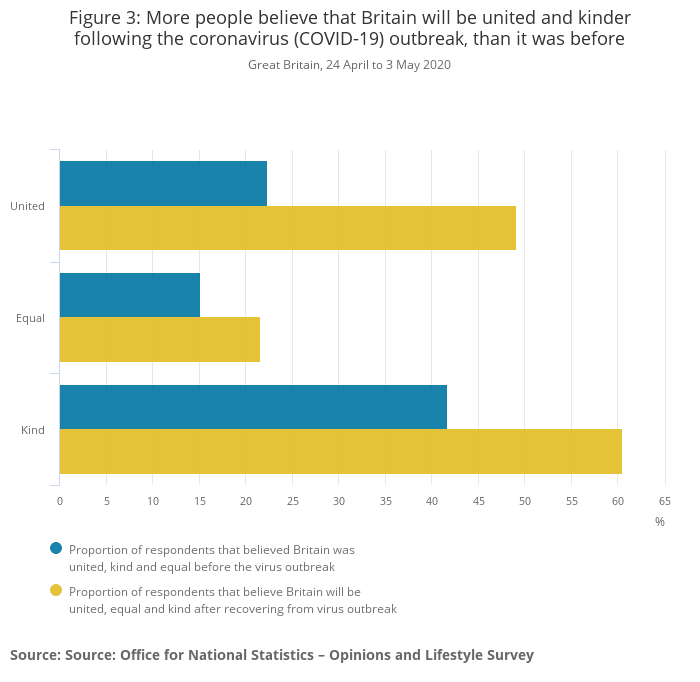

And the Office of National Statistics found a huge increase in the number of people who felt the impact of Coronavirus would lead to the UK becoming a kinder, more united and more equal society.

A more recent study by the ONS has now found an increase in feelings of happiness as overall anxiety about Coronavirus has declined.

It's seems apparent that the virus and lockdown have shifted our perception of what we value. There is a greater appreciation of our dependence on each other in the community and an acceptance that what someone is paid is not necessarily reflective of how important their job is. Couple that with a government failure to manage the response to the virus (particularly in the UK and the US) and you see that there is a new lens with which people are considering the change they want to see in society.

We want to be better and to do better.

The fact people have more time to consider what's happening to society can't be ignored either.

Which brings us to the money that people have available to give.

3. Available wealth

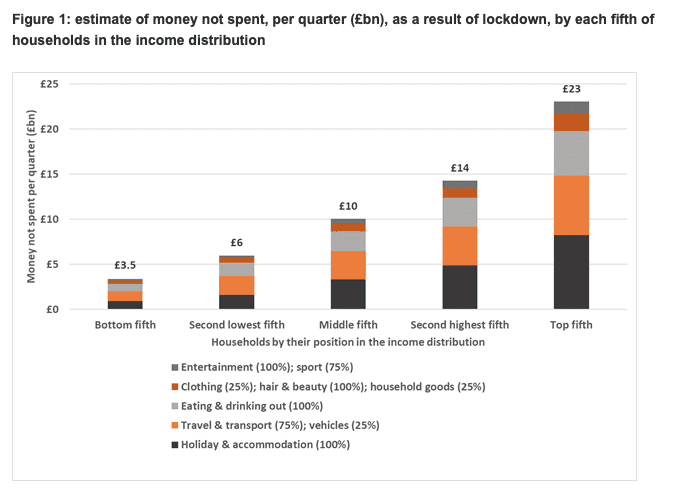

Many people report that with little to spend money on, they are paying off debts and building up savings. It is estimated that in the UK, the wealthiest 20% of households will have reduced their spending by £23 billion in three months of lockdown.

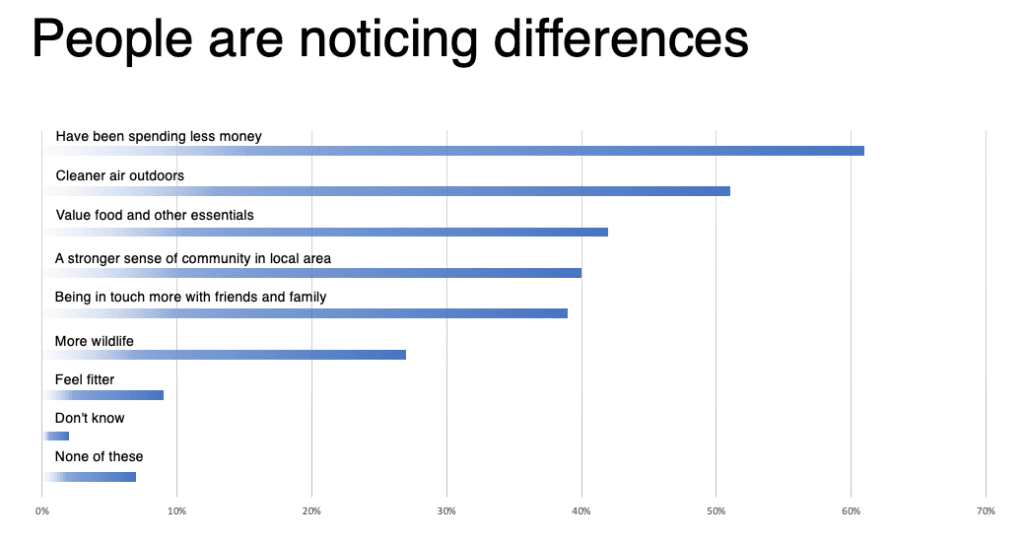

And as well as spending less, The Food, Farming and Countryside Commission survey found people are recognising the benefits of this new way of living.

As I've pointed out, you need to actually have money to be able to give any away. But the evidence indicates that a significant number of people – particularly within the Civic Core that give most to charities – are in fact significantly better off in terms of disposable income. We shouldn't under-estimate the financial stress that some people may be living under, but it appears that they will not be in the majority.

This highlights that it is numbers that are important. Not scary headlines in newspapers. Dr. Beth Breeze from the University of Kent wrote a very good examination of the media and public response to giving in the 2008/09 Great Recession (PDF) which concluded that frightening stories about a collapse in giving didn't represent what was actually happening in reality, as there was...

"...no straightforward causal relationship between economic conditions and the amount of philanthropic spending that takes place."

And further recommended that...

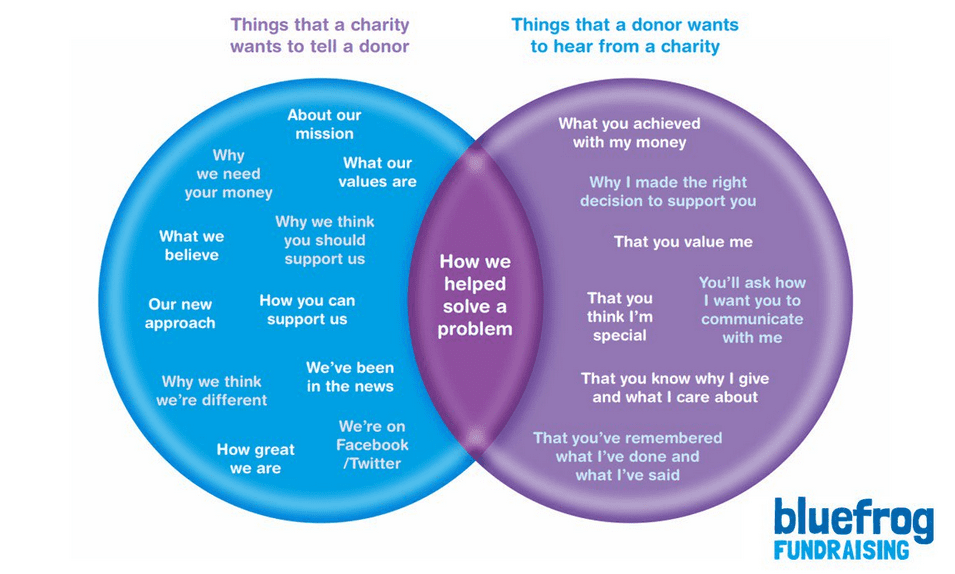

"...the most important strategy for donor fundraising is thus continued focus on donor care and maintaining effective communication with donors so that the importance of their support remains clearly understood."

And it's that last line that needs emphasis. In the Bluefrog ongoing study into supporting charities during the time of Coronavirus we found that being asked for help was a powerful driver for giving – If you cancelled appeals and failed to ask for help, it was assumed that you didn't need your donors' support.

In the next week or two, we will be releasing our third round of research about what donors think about giving during the pandemic, but the overwhelming response is that they don't feel they are hearing much from charities at all.

Perhaps more importantly, donors told us that they were wondering why 'their' charities had not been in touch to tell them about how beneficiaries had been impacted by the virus and how they had adapted their services.

The road ahead

There are still major challenges to be faced. The number of infections in the developing world is growing, a second wave following softening lockdown restrictions (in the UK) seems more likely and we don't know how the government will manage the repayment of the loans we have taken on to fund the response to the Coronavirus – though it looks more and more likely (at least in the UK) that we won't return to austerity. Instead we may see the development of some form of national wealth fund, there are calls for small business debt to be written off, suggestions of a green recovery plan and we do not know what will happen with regard to Brexit.

But what will be important for charities will be how we respond in terms of our fundraising activity.

Those charities that have been asking have seen record-breaking results. The first appeal that Bluefrog mailed out in the very early days of the lockdown generated an ROI over 330% higher than that received from the most recent (very good) Christmas appeal. And they were not alone - every other appeal that I am aware of (bar one) did incredibly well – both to warm and cold audiences.

If people want to see a kinder, fairer new normal, it will be down to charities and campaigning groups to make that happen. And they will need to be funded. From what we see at the moment, it would appear that donors are happy to be the engine of that change and many people have the resources to be part of the change that they want to see.

Next week, I'll be sharing more ideas on what charities could do as part of their fundraising plans for the remainder of this year and 2021. This will be at the Individual Giving Virtual Summit presented by Agents of Good and Bloomerang.

This is being run over three days and will work for differing time zones across Europe and Africa, the Americas and Asia and Australasia. As well as me, there will be presentations from great fundraisers such as Ken Burnett, Lisa Sargeant, Beate Sorum, Tom Ahern, Jeff Brooks and many more. If you are starting to plan what you will be doing next in your fundraising plans, can I strongly suggest that you sign up.

And finally, I'll be sharing the third round of our study into giving in the time of Coronavirus. We are recording that at the end of the coming week, so it should be available early during the week of the 15th June. Please subscribe (via the blue box at the top) to have it delivered straight to your inbox.

Tags In

Related Posts

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

[…] While a third of charities reported a decline in voluntary income last year, the picture seems to be improving. However, there’s still an air of uncertainty. In fact, experts anticipate huge changes to the economy, social changes and general available wealth will greatly impact fundraising in 2021. […]

[…] By: How charities are planning their 2021 Christmas campaigns | Raw London by How charities are planning their 2021 Christmas campaigns | Raw London […]