How to raise money to build a cathedral (medieval edition)

One of my key learnings from my conversation with Giles Pegram (you can listen to the podcast here) was the recognition that the techniques he used for the NSPCC appeals were not new - they dated back to the middle ages.

So after our chat, I hunted down a book that Giles had mentioned, Foundations for Fundraising, written by Redmond Mullin in the mid-1990s to dig a little deeper into the approaches used by our fundraising ancestors.

It's remarkable stuff.

Redmond details the approaches used by fundraisers to raise money for the building of the cathedrals at Troyes and Milan at the end of the 14th century. And guess what?

There's plenty to learn for today's generation of fundraisers. Take a look at some of the techniques they used.

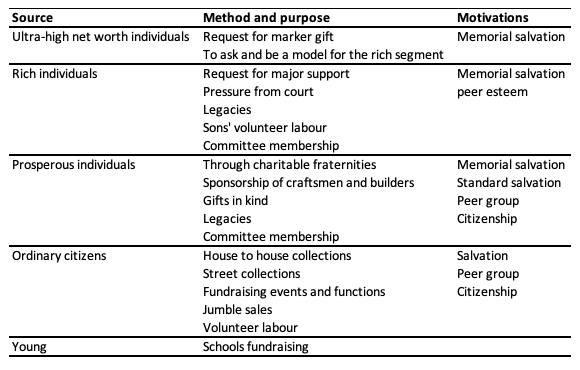

They kicked off with a focused and well planned approach to segmenting their market to encourage the local community to get behind the campaign and give at a level that was appropriate to their wealth and status – with benefits to match.

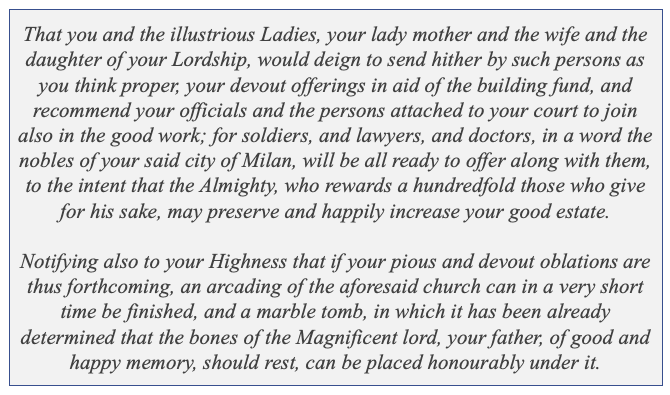

These early fundraisers knew that social pressure was important – gifts from the very wealthy could motivate those down the social scale to give. And membership of committees would ensure that everyone knew they had to do something. Jumble sales and schools fundraising were there for ordinary people and the young. And of course, they had a great offer – giving could guarantee your place in heaven. A letter sent by the appeal presidents of Milan Cathedral to their main prospect, the Conte de Virtu is included in the book.

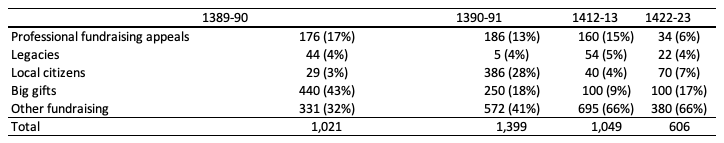

The records for Troyes cathedral shows just how sophisticated these programmes could be and, importantly, what influenced giving:

To explain in a little more detail, the Professional fundraising appeals were staffed and run in the region around Troyes. Legacies were important as the construction of a cathedral would take many years so it was essential to offer donors a means to guarantee their salvation with a gift after their death as well as within their lifetime. Local citizens is self-explanatory, Big gifts came from rich individuals, Other includes sales of relics, collection boxes, special masses and many other categories. Some cathedrals even had sponsored bell-ringing sessions where you could hand over a few quid and ring away.

But it's the fluctuations in income that tell an important story.

Why did gifts from local citizens surge in 1391? There was a disaster when the nave fell down and the local people wanted to save their Cathedral. Connection and need received a massive boost.

What happened to the professional fundraising appeals in between 1412 and 1422? Check your history books and you'll see the Battle of Agincourt was being fought a few miles away and impoverished the surrounding countryside.

Why did the Big gifts fluctuate? As we've seen in the example from Milan, the main donors were signed up early on to apply a little social pressure on other potential donors.

£300 came from the Chapter (the governing body), £40 came from the bishop, £100 from the Duke of Burgundy, £200 from King Charles V, £50 from the Pope. The Duke of Burgundy gave £100 in 1412 but after he was assassinated a few years later, his replacement, the new Duke of Burgundy also gave £100. And they say it's an ill wind...

The fact is, these techniques are the ones that successful fundraisers use today - particularly for mid and high-value fundraising. What history reveals is that the principles for fundraising have remained constant over history. Our role as fundraisers in the 21st century is to apply this practice within a world of changing context and opportunity.

And don't forget, as fundraisers we have a long and important heritage. That is something you should be proud of.

Key takeaways

- People will give to what they value.

- Commitment and connection are important. Those closest to a cause are most likely to give.

- Support is best secured through personal approaches from those who are already giving.

- Stay in touch with those who are giving and keep them aware of progress.

- Remember to identify and answer the donors' needs.

- Potential donors should receive a request that is appropriate for their position.

- Build a movement - not just a means to ask for the odd gift.

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?