The Fundraising Ecosystem

I’ve now completed the analysis of Bluefrog Fundraising’s qualitative research into the opinions of donors regarding the safeguarding stories that hit the headlines in February.

The process of presenting the findings to clients and sector bodies has begun and we will be sharing them more widely later this summer.

But today, I wanted to highlight one specific outcome identified by our study that demonstrates the powerful relationship between the fundraising activities of different charities.

Back in 2011, I described my concern that fundraising seemed to be following a model of development that was frighteningly close to Garrett Hardin’s concept of The Tragedy of the Commons, where increasing amounts of pressure on the pool of donors resulted in flat-lining or a reduction in giving.

But I hadn’t fully appreciated just how important the interaction between charities, donors/non-donors and the news media actually is.

It has been blindingly obvious, but rather than fundraising operating as a series of independent actions undertaken by independent charities, it appears to demonstrate many of the qualities of an ecosystem.

This is because people tend to see 'charity' as a broadly homogeneous set of organisations. Donors build ‘portfolios’ of charities that they choose to support (or exclude) whilst adopting a number of strategies to manage the competing demands for their donations. And it is this approach that has some important implications for fundraising.

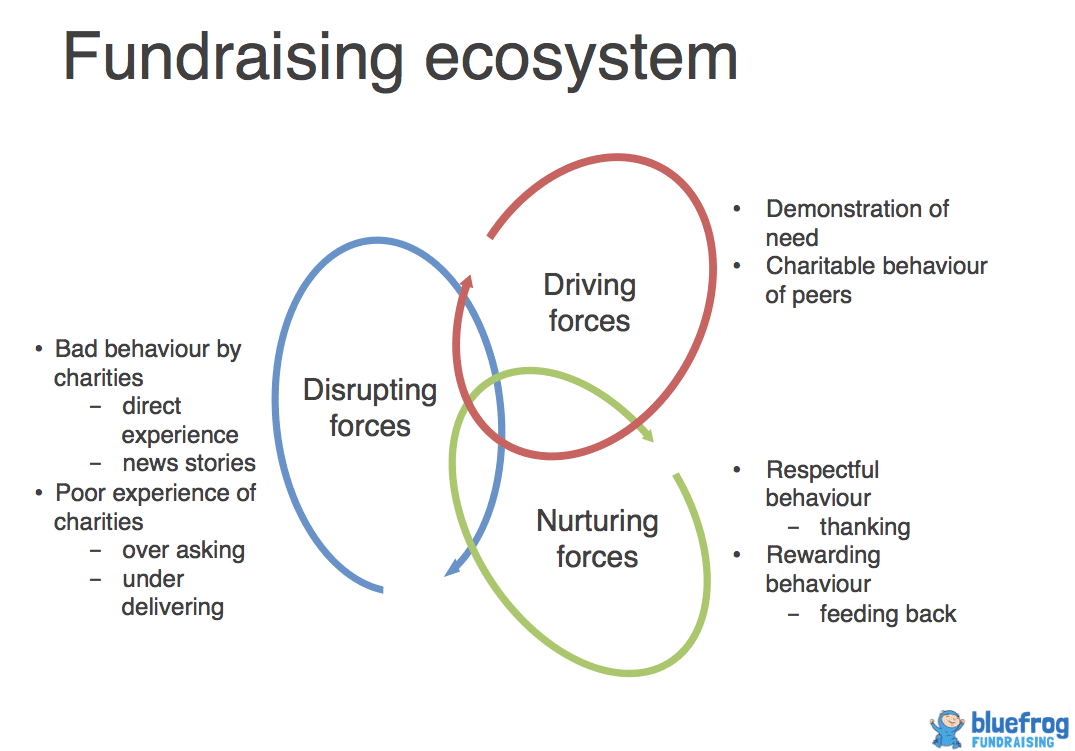

There appears to be three important factors within the fundraising ecosystem that have a particular influence on decision making. All are obviously subject to the donor having access to the financial resources to enable a gift to be given to charity in the first place, but all are interrelated. These factors are:

Driving forces

These are directly related to the initiation of giving. They will be direct requests for help through appeals, or the demonstration of need through news stories. But donors need more than this. They also need to know what they are supposed to do.

In our research, we often find that donors are searching for clues (or rules) about how much they should give to charity. In this respect, it is interesting to note the influence that the aggressively adopted and promoted £3 a month offer had in the UK in terms of limiting the sector's growth once the early novelty of the technique had worn off.

Alongside this, we also found that the charitable behaviour of peers plays an important role in influencing giving. If your family or friends are favourably attuned to charity, it is highly likely you will be as well.

Nurturing Forces

These reflect the positive actions that charities can take in response to a gift. Respectful behaviour such as thanking promptly and responding to donor requests are incredibly important, as is behaviour that rewards, such as feeding back on how the donor’s money has been used. This reinforces the decision to give and prepares someone to give again.

Disrupting forces

This is 'bad' behaviour – a failure to stay on task, aggression, delivering inappropriate communications or a failure to thank or feedback. It is often experienced directly or heard about via negative news or third party stories. Worryingly, in our safeguarding study, 'big charity' was a byword for questionable behaviour across the sample. Time after time, donors had a story to share about how a large charity had let them down or disappointed them. Happily, they also tended to have another story about how a (usually) small charity had delighted them which rekindled their faith in giving.

And this trade off lies at the heart of the ecosystem. When donors have been annoyed or upset by a large charity, it is their relationship with smaller, donor focused organisations that stops them losing faith with the sector. The consideration and respect donors receive from organisations that show they value them keeps the gifts flowing – to all organisations – large or small. Whether it is a kind word from someone at their local church, support from a friend or even a good thank you letter from a mainstream charity, these actions appear to be central to sustaining the donor and helping them maintain their charitable nature.

There are some big charities that obviously treat their donors very well, but if donors are to be believed, they are not as common as they should be.

And though it might appear that some charities view authentic and heartfelt thanking and feedback as an expense, it is one that is well worth paying for. Many, many hours have been spent debating why the sector seems to be stuck in a state of stasis. The answer may well be that instead of having too many charities, we don't have enough small charities nurturing donors - or large charities willing to copy their approach.

It would appear that rather than add pressure to the system, small charities benefit all charities through their existence, simply by providing a very real and positive experience of giving.

This first appeared on queerideas.co.uk

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?