What do donors need from you?

As fundraisers we are in a very fortunate position. We have more advice available to us through books, blogs, videos and conferences that any other generation in history.

But that presents a peculiar set of difficulties.

How on earth do we differentiate between the good stuff that will actually help and the crazy, flash-in-the-pan idea that’s going to burn up time and money and leave us with a group of ‘donors’ who don’t really care about us or our cause?

A huge amount of the advice that makes its way through to the sector can be pretty poor. Whether it comes from a world renowned business guru or even a hot new pop-psychology blog, it can be as useful as an inflatable dartboard when it comes down to boosting a bottom line.

But we shouldn’t be surprised. The world of business (and fundraising) is littered with failure. Decades of new product launches, re-launches and promotional campaigns show that human beings are rather poor at identifying what other people want. Unless we have superbly attuned emotional antennae, our own (or someone else's) views, beliefs and experiences are always going to get in the way.

Success – when learning about anything – depends on the ability to identify what information and advice will be of most value. To my mind there are three key characteristics of good advice. It normally is:

- specific to your situation or the problem you need to tackle

- able to withstand examination

- detailed

That’s why I find my most important resource materials today are interviews with donors. I read hundreds of them as part of the research we undertake for our clients. And they stand alongside books like Asking Properly, Relationship Fundraising and Designs for Fundraising as essential to my development as a fundraiser.

In those interviews, donors tell me about their biases, their opinions, their motivations and the barriers that prevent them giving more. And I’m always surprised at what I learn.

Whether they are supporters of hospitals, traditional charities or even political parties, the reasons why people give (or stop giving) are always personal to them. They will talk about how they are connected to a cause or share stories of trauma that may go back decades. I’ll find out how they felt they were treated as a donor and see what they want to do to change (a small part of) the world. I’ll even find out why some donors will never get more than a few pounds or dollars to a specific charity, whereas another very similar organisation will receive a legacy of tens of thousands.

But as a fundraiser, my role is to go through the myriad of conversations and identify patterns that can be applied strategically to ensure donors receive communications that bring them close so that we optimise income. But what continues to surprise me is the fact that success can have very little to do with the work the charity is actually undertaking on the ground. Instead it relates directly to how the charity answers the needs of a donor.

Donor needs in practice

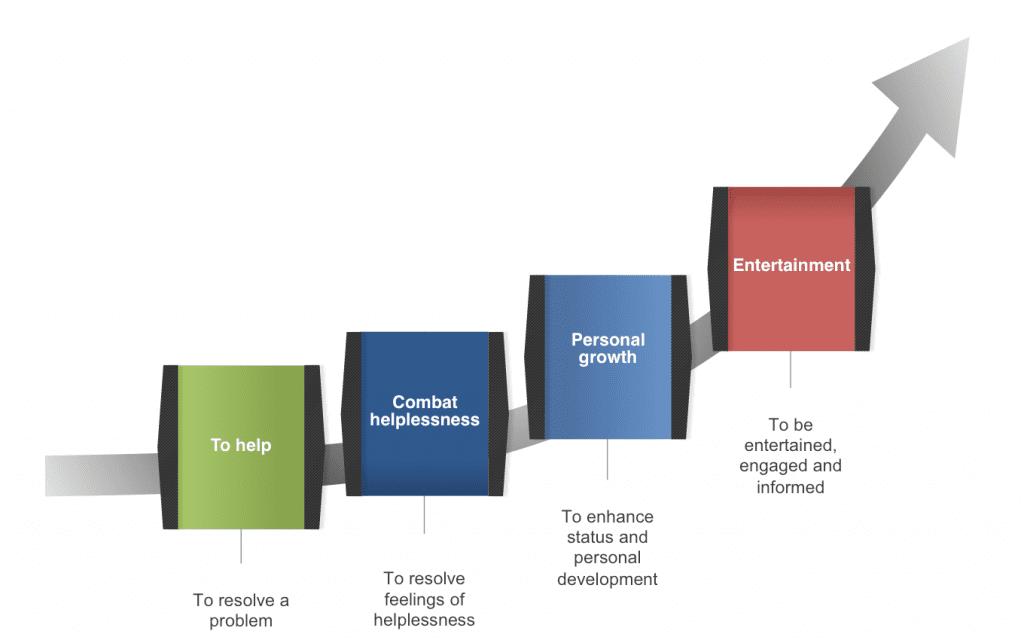

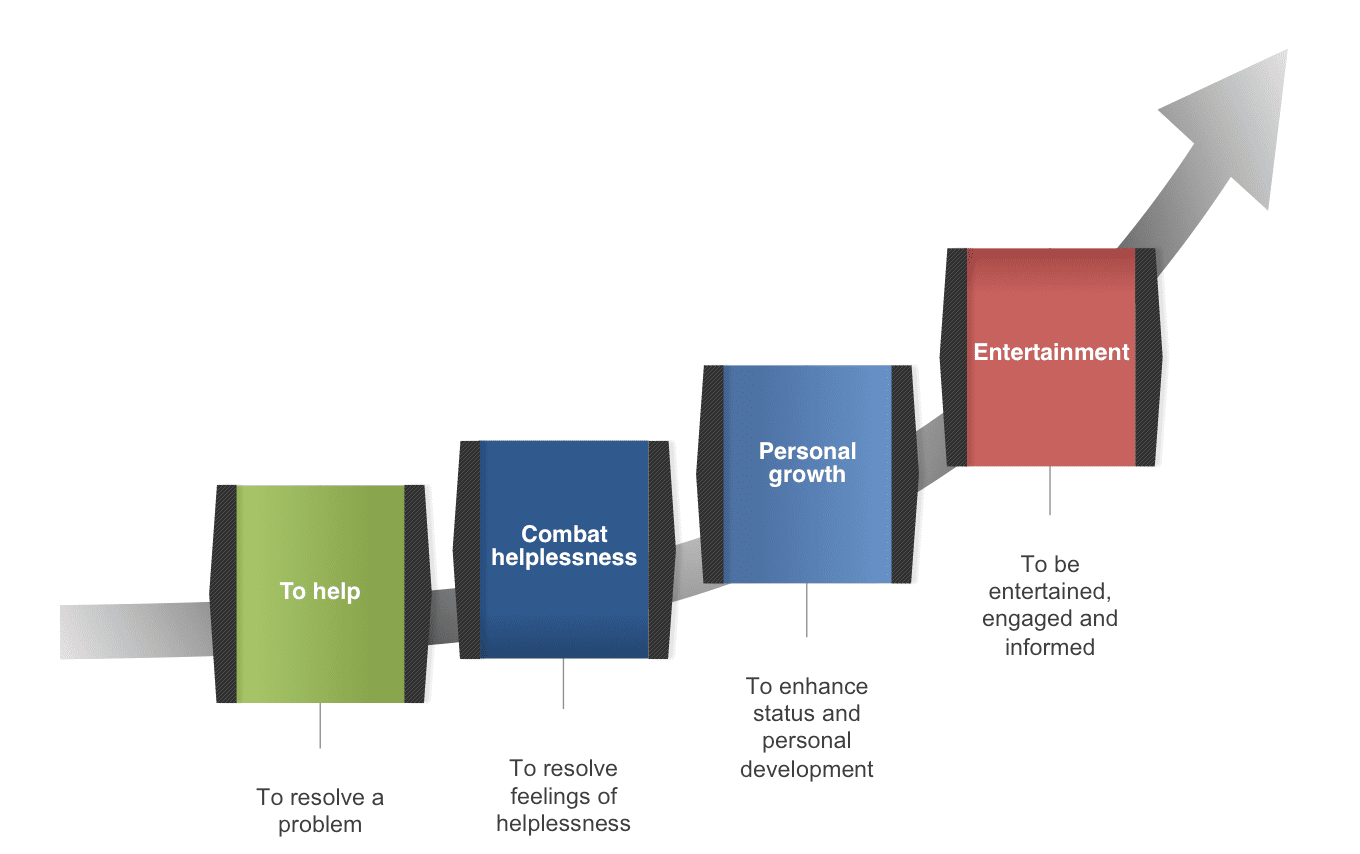

Of course the charity has to give the donor a chance to resolve a problem. To Help is the primary need state. But that doesn't help explain why they might choose ActionAid over Oxfam or Marie Curie over CRUK. And that is what we – as fundraisers – need to do.

Even a completely inexperienced fundraiser can get a few pounds or dollars from a surprisingly large group of people just by asking. But what's tougher is building a relationship that results in increasing levels of engagement and loyalty.

That can only come from answering deeper psychological needs – such as a donor's desire to tackle feelings of helplessness in the face of a disaster or the impact of a disease. Giving is not just a means to make a difference but is an opportunity to take control of a frightening or unpleasant situation.

But beyond this lies the areas of personal growth where donors are recognised to be important partners and brought 'inside' the charity, perhaps through the development of a new way of supporting a cause that avoids some of the more coercive techniques that helped stall the growth of the sector over recent years.

And then there is the need to be 'entertained' by our work – which doesn't mean that we need to make people laugh. But we must communicate with donors in a way that ensures they actually want to read and listen to what we say. We achieve that by making our communications both relevant and enjoyable. The secret to that is simple. We need to listen to them, show them that we know who they are and deliver what they want. Which brings us back to research.

Fundraising isn't rocket science. But all too often it's made to appear far more complicated than it is. Often by people who should know better. The best consultants you can employ are your donors and they are by far the cheapest too. So when creating your next appeal, don't start with the reason why you need the money. Instead, call up some donors and ask them why they give to you and use that perspective to produce your brief.

Your appeals may be very different as a result - but then again, so should your income.

Tags In

Related Posts

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

[…] written quite a bit about donor needs. It’s good […]

[…] am stretching an analogy to make, is that we need to package up fundraising in ways that answer our donor’s needs rather than simply describe what a charity is […]