When culture doesn’t translate into giving

Fly to one of the international fundraising conferences and you’ll no doubt be presented with more great fundraising ideas than you can shake the proverbial stick at. You might well be planning your next big campaign before the wheels on your plane touch down on home soil.

But - and here’s the thing - how do you know it will work?

Search for international marketing failures and you’ll find a seemingly never ending list of monumental cock ups (some truer than others).

From the slogan, Come Alive With Pepsi translated as Pepsi Brings Ancestors Back From The Dead in Mandarin. The hair straightener / curler that was sold in Germany as the Mist Stick, where mist translates as manure. To Home Depot’s failure in China when it’s 12 stores were closed down because customers kept away. Why? Because the company failed to understand that DIY was seen as a sign of being broke.

If huge corporations can make these mistakes, why should charities be immune from the same errors when we know that different cultures have very different attitudes to giving and asking.

Take something as simple as telephone reactivation programmes for regular giving. In some Nordic countries, success rates can run as high as 50%, whereas in some south-east Asian countries they can be under 5%.

The techniques and media channels are usually similar, but the results vary enormously. That’s because, just as in the corporate world, cultural differences come into play. By paying attention to what people from different countries and cultural groups need when they interact with a charity, a disaster can be avoided or a good campaign turned in to something great.

At Bluefrog Fundraising, we’ve become increasingly aware of the importance of cultural differences between countries as a result of the growing amount of international research and fundraising that we’ve undertaken. Over the last few years, we’ve spoken to donors in the US, Canada, Australia, Ireland (and of course, the UK). We’ve discussed attitudes to matters as diverse as branding, legacies, mid-value gifts, in-memoriam giving, why donors lapse and what motivates them to give more. And we have been amazed by what we’ve uncovered.

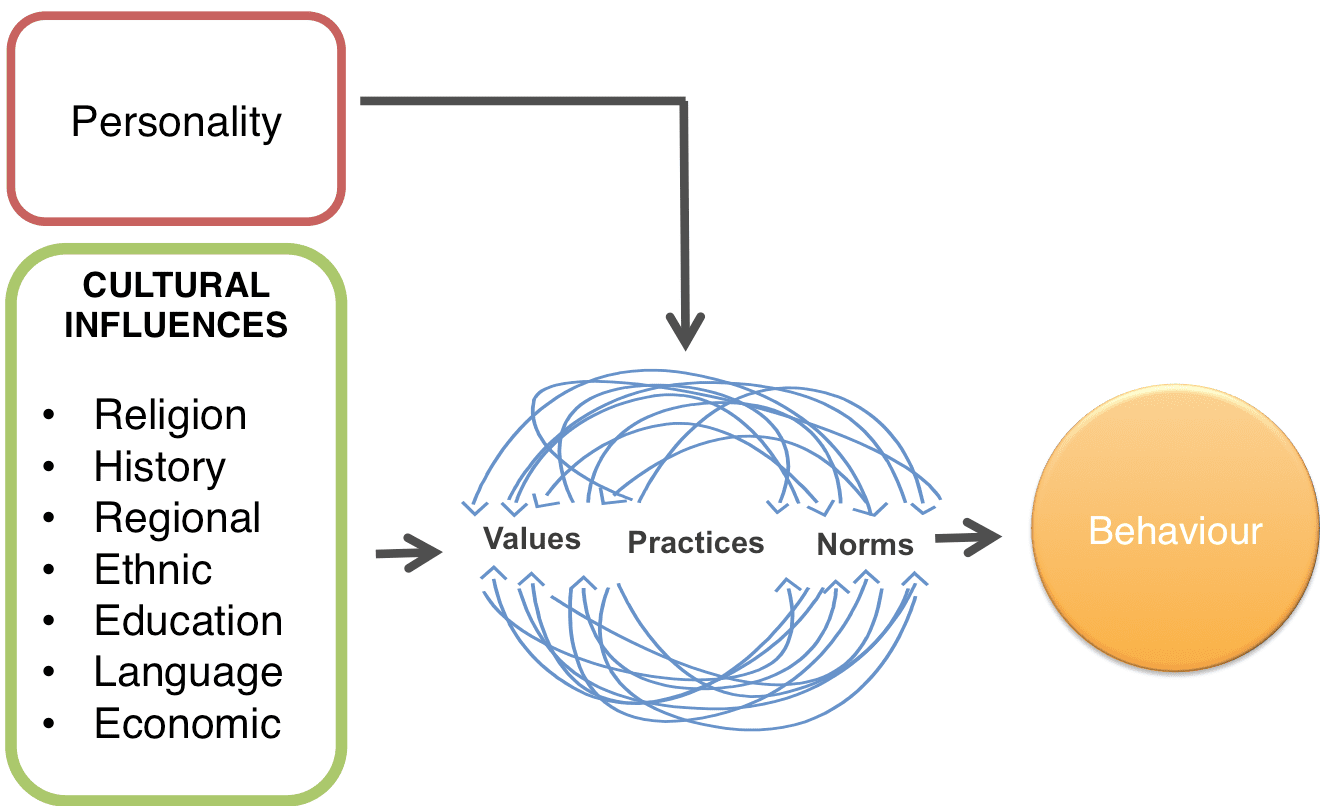

A wide range of factors including religion, the economy, and history have a massive influence on how donors behave. Here's a (highly) simplified model of how this works.

Our starting point is the fact that people are pretty much the same throughout the world. Some are nice. Some aren't. Some care and some don't. But culture has a big influence on how people perceive fundraising communications and also on the type of relationships they want with charities. Combine the two forces and they translate to nationally (or regionally) distinct sets of values, practices and norms that influence how someone is going to behave when asked for a gift.

Take public recognition for example – offering people the chance to show off a little about their giving. This can be very attractive for wealthy Americans (think names on the sides of hospital buildings) but can be a complete turn off for donors in Ireland where such displays are frowned upon. In a study we undertook in Ireland this summer, donors repeatedly shared a concern about how they would be viewed if they received public recognition for their giving. Or as one donor put it...

"Showing off about giving is crass. I would be ashamed."

We've also learned that giving can also act as a means to connect yourself to your country and community. In Canada for example, we found people felt that it was important to be seen as a 'good' Canadian and giving is a way to achieve this. Whereas in the UK, people would find this attitude confusing. British people are much more likely to be worried about how a charity will treat them rather than being seen as good Brits!

So, if you've seen a great new idea and you'd like to test it in your country, what should you do before you start spending money? We have a simple acronym that might help – FIT!

Find out what your donors think

I can't emphasise this enough. It doesn't cost much to discuss ideas with donors even with help from qualitative market researchers. Talk to your supporters about the idea, what they like and what they want from you. Not only will you get an idea of how your new idea might be received, you'll get insight into other areas of your fundraising programme as well. In all the countries where we've undertaken research our clients have been amazed with what we've uncovered. And frankly, so have I.

Interrogate the idea

Ask yourself why would it work in your country and why it might fail. The old adage that 'if it sounds too good to be true it probably is' really does apply to fundraising. Speak to a range of organisations who have tested the idea in other countries and ask them what they think and what they would do differently. Don't rely on one source.

Tweak it

Apply your understanding of fundraising in your country to the new product. Can you change price points, add or remove elements, change the language or even focus on a different way of support - legacies, in-memoriam giving, mid-value? Don't be afraid to adapt the product for a test (alongside the original model). If you have undertaken donor research, then apply what you have learned.

Adopting approaches from different countries and cultures is a great way to boost your fundraising, But don't think that a simple transfer of an idea from one country to another is going to be good for your charity (or even the idea). Instead take notice of what is going on in your particular culture to work out what will be important to your donors and potential donors and customise the idea to make it your own.

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?