The case against the case for support

On the face of it, the case for support should be the key organisational tool for fundraisers, but having seen a fair number over my working life, I'd question how many are actually fit for purpose.

Tim Seiler, Director of the Fund Raising School at Indiana University and author of Developing Your Case for Support has provided my preferred definition of what we should expect from a case for support...

"The case statement focuses on or highlights factors that are critical in arguing for gift support and is typically tailored to reflect the needs and interests of the supporter being addressed."

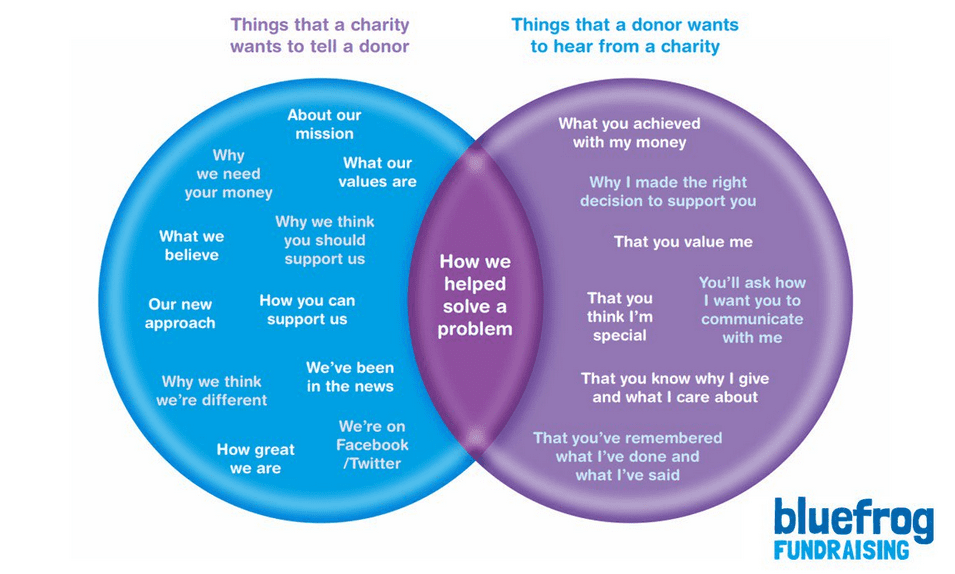

Which leaves me wondering why do so many charities fail to take into account the reasons why donors give when preparing their own particular case? And instead end up creating an internally focused document that defines what the organisation does and why.

To me, that's not a case for support. It's the basis of a strategic plan. Not something that too many donors are interested in. Adrian Sargeant and Jen Shang describe this situation rather well in Fundraising Principles and Practice...

"Too often case expressions are written from the perspective of the organisation, containing jargon and reasons that make perfect sense to those working inside the organisation but that have little relevance for donors or others viewing the organisation from the outsider's perspective."

As a result of this internal focus, the case for support will often cover a huge raft of information, including need, core beliefs, vision, the role of the charity, the 'unique selling point', the personality, the key services and – if you are lucky – even a little on the role of the donor.

Try translating that into an effective fundraising offer whilst you're under the watchful eyes of your organisational brand police and you're in for some fun.

I don't understand why it has to be so complicated. If we look at some of the key elements and ask ourselves what they offer donors, I'm not sure if we'd come up with much of an answer.

Even need isn't that important.

Alex Spanos, is a U.S. Billionaire who each year gives millions to a whole range of different causes. When he was interviewed about how he chooses what to support, he placed need firmly into context.

"I never give because I think there is a need. There are lots of needs. I give because its a programme I'm interested in and I think I can make a real difference."

And he's right. Even when we feature life or death stories our DM recruitment response rates remain pitifully low.

I'm not saying we can forget need. Far from it. It is essential. But there is so much need, it's simply not a point of real differentiation.

Moving on to the vision. This obviously can be inspirational when handled well, but when given too little thought, it can also get in the way.

I remember a number of years ago, being presented with a new strategic direction for a charity. There was a new case for support and we were charged with making it work for fundraising.

As part of the process, we visited a number of projects to gather information to use in appeals. At each project, we asked to see examples of the new approach in action and every single person we met said the same thing, "We haven't started that work yet."

It was Henry Ford who said that "you can't build a reputation on what you're going to do." But we still had to get appeals out and I ended up producing packs that were written for two audiences – the comms team and the donor. I doubt either of them was really happy with what they received.

And when it comes to the old favourite of the 'unique selling point' (USP), charities often seem to focus on an attribute that's unique rather than one that will help to sell the cause. Just because a charity can identify one aspect of its work that other similar organisations aren't promoting, it doesn't mean it's a good idea to adopt it as a key strategic platform.

A USP only matters if it matters to the donor.

So what should a charity do when building a case for support for fundraising from individuals?

To start off, I'd recommend that any team working on this particular problem should write Tim Seiler's definition on the whiteboard and refer to it constantly throughout the process. I'd then suggest that three key areas are worth concentrating on.

1. What can you offer donors that other charities don't, can't or won't?

This obviously covers far more than the opportunity to tackle a need. We know that donors value some elements of their relationship with a charity above others. This should be our starting point and might include...

- The opportunity to see how their money has made a difference.

- A means to demonstrate to others what they believe in or are part of.

- The chance to fund a specific area of work.

- Direct access to those helped.

- Invites to social events.

- Control over the relationship and communications received.

This post is also worth a read.

2. How can you make your appeal as emotionally rewarding as possible?

This might require featuring a specific areas of work or certain beneficiaries – which when looking at any charity working with people, will normally be children. Unfortunately any other group rarely offers the emotional rewards of helping a child.

I'm not saying that it isn't impossible to build an effective case for support that focuses on adults. It's just very hard work. When Bluefrog built lendwithcare.com for CARE International as a means for people to directly fund entrepreneurs in developing countries it was the result of almost two years of extensive research and planning. The result is an inexpensive means to recruit donors with over 50% of all lenders donating to CARE as well. We also found ourselves on the receiving end of some significant corporate support.

We were rewarded by fundamentally changing the offer in response to what donors actually wanted from a charity.

3. How can you allow your donors to be part of the narrative?

You obviously want to build a relationship with donors that brings them closer to your charity. This has two key benefits. First it will help you raise more money and second, it might encourage your donors to want to learn more about your charity (which, funnily enough, is what your comms team actually wants).

So rather than focus on the macro-story of your organisation, try articulating your work through a series of micro-stories that people can become part of.

By identifying a small number of beneficiaries or staff who agree to help you demonstrate to donors what their money is doing you'll build a group that have a real stake in fundraising. Your focus will mean that the information you gather will be of a higher quality and the subsequent impact on the donors far greater.

Couple this with offering donors the chance to do a little more, such as sending beneficiaries greetings cards (as in the case of child sponsorship) and you'll find that loyalty and response rates significantly improve.

Which, at the end of the day, is what any good fundraising programme should have as its goal. And if your case for support isn't helping you achieve this perhaps it's time to have a look at the case for writing a new one.

Tags In

Related Posts

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

Nice article. I like your views on the unique selling point and an emotionally rewarding appeal. The way we communicate is very important.