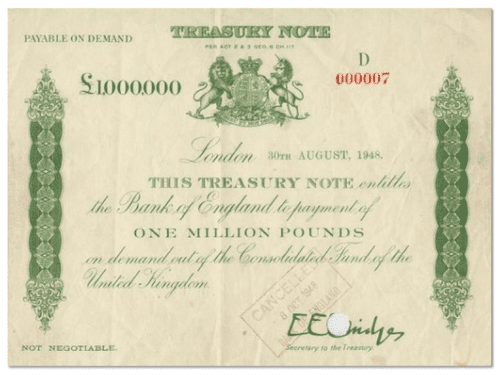

How to get a £1 million donation

The Coutts Million Pound Donors Report 2010 has just been published.

It takes a look at the condition of British philanthropy at the very top of the giving scale – which, as you might guess, covers gifts of £1,000,000 and more.

There were just 201 donations of this magnitude made in the 2008/09 financial year, with a pretty healthy combined value of over £1.5 billion.

That doesn't actually mean that money found its way into the hands of charities – half the money recorded was actually 'banked' in foundations for distribution over time. But the remainder was donated, with 58% going to hIgher education and 13% going to arts and culture.

'Traditional' charities didn't do too well. International aid received 5%, human services and welfare generated 4% and environment and animals brought in just 1% of the top-end gifts.

Which got me thinking about what universities, art galleries and theatres have that the rest of the charity sector lacks.

It certainly isn't need. In a matter of life and death, I'm sure that few people would prioritise a painting over saving a child's life.

And it's not like people are falling over themselves to give to universities, theatres, museums and art galleries. A paper published by Arts & Business – Arts Philanthropy: the facts, trends and potential estimates just 1% of the UK population give to arts organisations and the Ross-CASE Survey 2008-9 (that analyses trends in giving to universities and higher education institutes) shows that about 0.26% give to higher education.

The government has actively tried to boost giving to the educational sector. 2008-09 was the first year after the launch of the £200 million three-yearmatched funding scheme where, depending on the size of the donation, the government would match a donor's gift.

But that isn't enough to account for the large number of super-high gifts these sectors receive.

I'd suggest that one significant issue might be that many people working in the educational and arts sectors are actually used to dealing with very wealthy individuals and, as a result, are very comfortable asking for very large sums. We also need to remember that both sectors can also offer a very special type of recognition.

David Spinonla, Head of Individual Philanthropy at the Royal Opera House, explains how they treat people who donate £1 million or more:

"People who donate £1 million or more to the Royal Opera House are invited to become mebers of the Chairman's Circle and their contribution is also honoured on a glass panel in the Paul Hamlyn Hall, in addition to the supporter acknowledgements already in place within Royal Opera House print and in the foyer.

Royal Opera House philanthropists are offered an exceptionally wide range of opportunities to experience how their support is being put to use. Involvement is closely tailored to the interests of donors, taking account their preferences to specific art forms, artists or practicioners and their existing knowledge and experience. Our Chief Executive, Tony Hall, describes them as "a family", and donors relish the opportunities we offer to meet with artists and senior staff…and to see how productions are put together, from initial designs through to the creation of props and costumes."

It sounds pretty glamorous. Meeting up with stars, watching shows come together and probably the odd party to go to as well.

High value donors to universities are given very special treatment too. Take Oxford University for example. Depending how much you donate, you can be invited to join the Vice-Chancellor's Circle or The Chancellor's Court of Benefactors.

You'll be able to attend dinners, debates, receptions, balls and sporting events. The Court of Benefactors even has a ceremony of admission where you get to wear a rather groovy gown and 'bonnet'. Your name will also be engraved on the Clarenden Arch alongside other great benefactors such as Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and Sir Ernest Oppenheimer. And the most generous benefactors are likely to receive The Sheldon Medal.

It's all a rather long way from what many 'traditional' charities might be able to offer in the way of recognition. For many people, a cup of tea in an office in Islington might struggle to compete with dinner at the High Table or watching La Boheme from the wings.

But there are some things that can be learnt from these massively successful campaigns. And a number of these are spelled out by the author of the Coutts' report, Beth Breeze.

Rather sensibly, she didn't just collect information on income and expenditure. Beth also asked donors and fundraisers to share their top tips on fundraising and she includes them in the report. And here are just a few examples that you might find useful:

"Take your time and ask at the right time. It can take 3 or 4 years before a donor is ready to make a really significant financial commitment."

"Find out what benefits the donor would be pleased to get, as they are not always obvious or that difficult to fulfil. We give one major donor an annual staff car parking pass and he is delighted with it."

"Be prepared to give major donors access to the people within the charity that they want to speak to, including the most senior staff who can talk about strategy and the front-line workers who can explain what is happening on the ground."

"Major donors will rarely ask for formal acknowledgement, like naming opportunities, but they usually appreciate being asked."

"Involve your major donors as much as is appropriate. Million pound gifts come about because someone is passionate about what you do, so give them every opportunity to enjoy their passions."

"The bigger the donation, the more reassurance the donor usually needs. Give them every reason to trust you and believe their money will be well-spent for maximum effect."

Tags In

Related Posts

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

Your observations about the ability of arts organisations to attract high value donations are interesting, and the suggestions for how other organisations might compete are sensible and worth trying.

I think another explanation is that wealthy people are more status conscious than most others, and use the arts as a means to display status and network. Accordingly, it isn’t realistic to try and compete with arts organisations for dollars. Further, many wealthy people lack sympathy for people without opportunity, because they embrace the ready myth that their success is a byproduct of internal merit more than the good fortune of circumstance, or adopt other similar values which insulate them from compassion.

This isn’t to say there aren’t humanitarian or laudable people of great wealth — Gates and Buffet aren’t in this category, but they aren’t giving to opera houses either.

Nonetheless, the more status oriented principles I suggest could be leveraged to fund raise. If children’s service organisations hosted some form of gala event where participation was seen to demonstrate one’s generosity and social conscience, it might well increase funding to the sector. A universal and appealing theme like “Kids First UK” might help — but I think the organisations would need to work together to achieve such an outcome, and trying to do it singly would be prohibitively expensive and risky.