The strategic importance of valuing your donors

Strategy is a complicated beast at the best of times. Try developing one for a charity and you really start to understand the meaning of the phrase 'a little tricky'.

Most organisational strategies tend to concentrate on how the charity is going to tackle the problem that underpinned its original creation – from ending global poverty or developing a treatment for a disease right through to causes of more limited popularity like restoring a steam train.

Fundraising will be covered, but more often than not it is seen as a support service.

Money is obviously essential, but few people on the delivery end of the operation will find their heart all a flutter when they discover that they need to get involved in a little fundraising.

As a result, income generation becomes a means to an end. It's something people have to do rather than want to do. As long as ratios hold up and targets are hit, people are happy to leave fundraising on the back burner.

I think that is a mistake. And as I'm talking about strategy, I might as well emphasise that I think it's a mistake of strategic proportions.

Elevating fundraising to the core of the organisational strategy can make the difference between a charity being good and great.

Fundraising is tough. And when it is treated as a support service where a few complaints can dictate whether tools like the telephone or direct mail can be used, it can be almost impossible for a fundraiser to do their job effectively.

But when fundraising is part of the very DNA of the charity, where the need for funds is seen as important at every level of the organisation and where fundraising is seen as everyone's responsibility, the coffers are unlocked and money flows in.

That's because decisions are made with the needs of the donor in mind. And that can offer a very strong competitive advantage.

I'm not suggesting that charities should change the mission statements which define their reason for existence. I just don't think that they can drive all the business decisions that a forward-looking charity needs to make.

And on this point, we can probably take a few leads from organisations who have successfully identified a competitive advantage and exploited it.

Hyundai in the USA, for example, have seen that the recession isn't necessarily a good thing for car sales and have recognised this in their marketing strategy. They now offer assurance with all new sales. In short, if you lose your job within twelve months of buying a new car, you can hand it back for a refund.

Hyundai have identified that their customers have a need for peace of mind and supplied it. As a brand attribute, it's incredibly authentic. It's not just a promise. It's a guarantee.

So what can charities learn from this?

To answer that question, I suggest you take a look at a paper published by David J. Collis and Michael G. Rukstad in the Harvard Business Review, Can You Say What Your Strategy Is? (PDF) In it they debunk some of the myths about strategies needing to be complicated to be successful. They actually say that if you can't articulate a strategy in less than 35 words it is probably holding you back as few staff will understand what it is or how it relates to them.

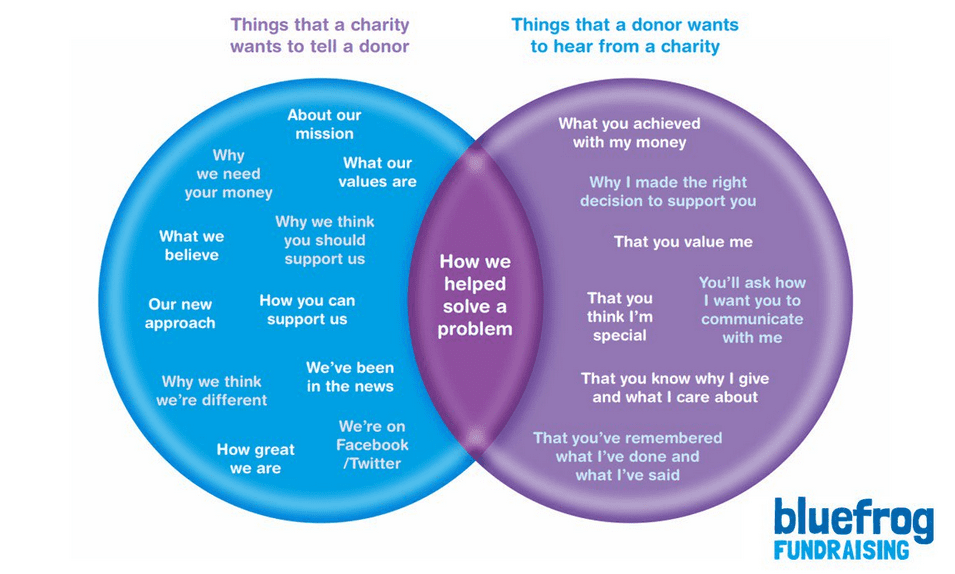

But more importantly for us, they talk about competitive advantage and the importance of identifying the strategic sweet spot of a company – the place where it can meet customers' needs in a way that rivals can't, don't or won't. I've recreated their chart below, obviously replacing the customer with the donor.

In a crowded charity market, the identification of this strategic sweet spot can be difficult. I've written before about research where donors have struggled to identify the difference between charities with similar aims.

So what should you do?

As the chart suggests, you should look at what your donors actually need from you and identify how you can deliver what they are looking for.

All the evidence points us in one direction – that donors want to know more about how their gifts are making a difference.

If we ignore what donors need, they disappear almost as fast as we can bring them on board. We're like the fundraising equivalent of a competitor on It's A Knockout trying to fill a bucket with a massive hole in the the bottom. A load of effort for not much reward.

This is what we tackle by changing our strategic view of donors. Few charities are set up to effectively engage and involve supporters. Feeding back on how gifts have been used is rarely seen as a core task. As a result, information gathering can be incredibly disruptive to day to day work and soon finds itself way down the priority list.

And that dramatically holds fundraising back.

By building the needs of the donor into a strategy we effectively agree to open the doors of our charity to our supporters. And by delivering on this promise – through demonstrating their individual impact – we ensure they sit down and stay.

And that's when a strategy really starts to pay dividends.

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?