Why we should be worried about where donors get their information from.

I've just had my first debrief on a significant qualitative study that Bluefrog Fundraising has undertaken looking at what UK donors think about the recent series of safeguarding stories.

I've just had my first debrief on a significant qualitative study that Bluefrog Fundraising has undertaken looking at what UK donors think about the recent series of safeguarding stories.

We've uncovered some things that you might expect, but a great deal of what we've found has been a surprise even for someone like me, who has been in fundraising for the best part of thirty years.

Our plan was originally to share our findings with Bluefrog Fundraising clients, but there are a number of elements that relate to all charities so we will publish some findings more widely if there is sufficient interest.

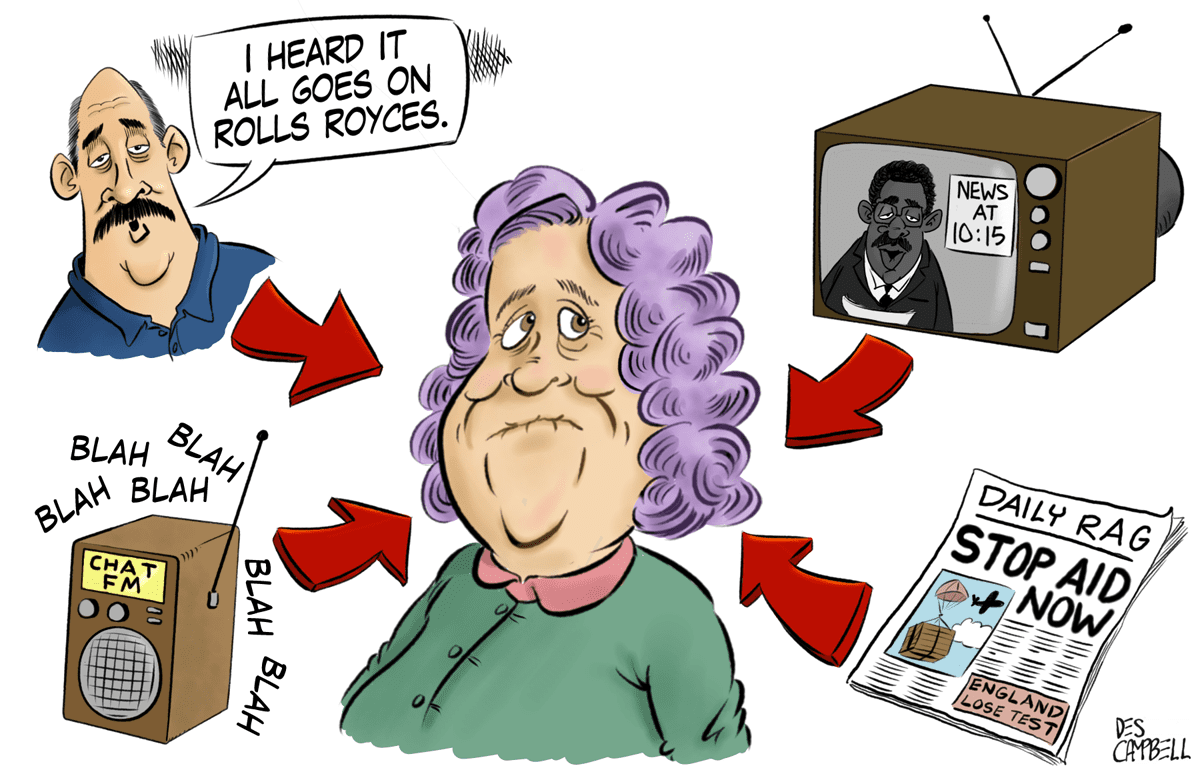

One area that has stood out is how dependent the giving public are on word of mouth and the media for information on charities – even including the ones that they support.

Very few people that we spoke to could provide us with much detail about what any charity actually did with their money. Medical research charities were seen to fund scientists wearing white lab coats and donors had a pretty good handle on the work of organisations like the RNLI and Marie Curie. But when it came to organisations with a complex brief – such as development charities – donors really couldn't give us much of an idea of what they did beyond a very basic description of providing food aid, vaccinating children or digging wells.

And don't forget that these were engaged donors. Some had been supporting development charities for as long as I've been in fundraising, but when the safeguarding stories hit the front pages it served to show them that they knew very little about how the organisations they supported actually functioned.

When we asked them to describe an aid worker, they struggled. Gap year students were mentioned. Some thought local people might be involved at times of an emergency and others came up with the idea of a 'crack team' being flown in, but the lack of real understanding of how aid is delivered left them a little lost.

Because of this, the news stories filled an information void. As one donor said...

"This is all a blank slate and you've left us to fill in the gaps."

As conversations continued it became clear that donors were far more reliant on third party sources for information on charities than we had imagined. Google "charity front pages", click on images on your search results and you'll see what charities are up against. Though not everyone reads the papers that fill your screen, they drive the news agenda – and that has had a profound impact on donors' giving behaviour.

Stories of charity incompetence, high administration costs and malpractice are common in the news and that has had an impact – even on the most committed donors. And though many acknowledged the possibility of media bias, their perceptions illustrated that negative stories hadn't been ignored.

For example, against all the evidence, donors think charities spend much more on administration than is the case in reality.

Why? And why don't charities address it?

So often the important numbers are hidden in annual reports and ignored in appeals and feedback. Nature abhors a vacuum so the gaps are filled with guesses and estimates that have more to do with the criticism of a few charities than represent the reality.

Maybe it's because cost ratios don't feature in the brand or talking about admin can make some of the toughest fundraisers feel uncomfortable? But the result is that donors are left to assume the worst.

But even if the actual numbers are featured, it's unlikely that they would be read by more than a handful of supporters. In many cases we found donors were not reading newsletters because the content was deemed impenetrable and/or repetitive. But more importantly, charity communications failed to give them a sense of what they had helped achieve with their donation. That made it very easy for them to lay unopened in a pile on the floor on their journey to the recycling bin.

Poorly conceived publications push donors away from reading them (and that includes appeals) meaning that the information gap between charities and donors is forced wider apart. And sadly, will continue to grow unless fundraisers do something about it.

Thankfully, donors still want to know what their money makes possible, so they won't always ignore letters and emails. They simply need communications that answer their needs. We'll be featuring more about that and other important findings when the report is published. If you are interested in seeing the full paper let me know by emailing things[at]bluefroglondon[dot]com and we'll be in touch when it is finished.

Tags In

Related Posts

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

[…] giving in spite of the mailings that they receive – not because of them. Just as we found in the UK safeguarding study from last month, a surprisingly large amount of the information that American mid-value donors […]