This is not fundraising

Over the last fifteen years or so, we’ve seen a fundamental change in how we raise money. For most of the twentieth century, fundraising was about engagement.

Over the last fifteen years or so, we’ve seen a fundamental change in how we raise money. For most of the twentieth century, fundraising was about engagement.

It was about recruiting new donors, nurturing them, getting a second gift, then a third and then moving them to regular giving (which we used to call committed giving). We would maintain their support with feedback that showed them the impact of their generosity until finally we received the ultimate gift – a legacy.

It was hard work. It wasn’t cheap. But when done well, it produced great returns.

But in the late 1990s, things changed. We discovered face to face fundraising and the power of interruption.

Face to face fundraisers would stop people on the street and sign them up as regular givers. At a stroke, we could cut out the hard work (and expense) needed to engage people before we gained their ‘commitment’.

We soon worked out that these donors were different to the traditional donor. They were younger and they didn’t give to our DM appeals. But because they gave through a Direct Debit, that didn’t matter. After all, these donors gave twelve times a year.

There was the growing problem of attrition, but the face to face agencies introduced guarantees and it became something we learned to live with. After all, if these new recruits weren’t responding to mail packs, what could we do?

And slowly the structure of donor bases changed. Rather than recruiting older supporters with an engagement to the cause, many charities were increasingly likely to be funded by younger people who didn’t seem to want much of a relationship. They were regular givers. But they couldn’t necessarily be described as supporters.

And if these donors didn’t want to engage, charities were a bit stuck. Crossing fingers and hoping for the best, replaced old-fashioned fundraising. Donors grew to resemble a commodity where they were bought and sold for up to £100 each. Ironically, if they were the sort of person who was too busy or too disinterested to cancel a Direct Debit, it increased their value.

This all created something of a problem.

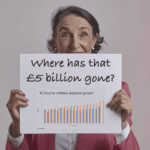

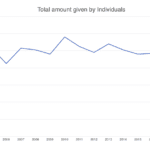

If you look at what’s happened over the last five or six years, the income from individuals for many charities has stagnated. Yes, the recession has had a great deal to do with this but so has the fact that many charities have been primarily recruiting unengaged donors for the last fifteen years.

CAF figures show that the percentage of donors who give via Direct Debit has been stuck at about 30% of people who donate to charity since 2006/07. When the PFRA reminds us that face to face recruited 2.2 million new regular givers between 2009/10 and 2011/12, it makes you think we might be simply swapping donors on some form of philanthropic merry-go-round.

And the implications appear to be worse for legacy income.

Remember a Charity reports (PDF) that the number of Wills that include a charitable gift at probate has increased by 10% in the first part of this century. But take a visit to the Charity Commission website and have a look at what’s happened to the legacy income of many of the big charities over the last five or six years or so. You’ll see that legacy income is, by and large, flatlining or even in decline.

The fact is that the legacy prospect pools for some of our biggest charities are rapidly shrinking.

So what should we do?

I think it’s about time for a change of focus. To value instead of cost.

Cheap regular givers are usually cheap for a reason. They have low levels of engagement. Commitment doesn’t happen overnight – it is the result of hard work.

This isn’t a criticism of face to face. As a technique, it has recruited hundreds of thousands of new supporters. Without it, we would be poorer.

My concern is simply an over-reliance on interruption – in all its guises. And the long-term implications of the technique.

Mobile, for instance, has been presented as the future of fundraising. Like face to face, it recruits donors cheaply. But the levels of loyalty and interest demonstrated by mobile donors are also incredibly low. Click through rates are tiny. And if a donor isn’t going to click through, it doesn’t really matter what information we put on our mobile responsive website, it’s unlikley to be read. All for an average gift of £3 a month.

So where are the most valuable donors?

They can come from any source (even your own warm file) but perhaps direct mail, press and online offer the best return, particularly at the moment. And particularly direct mail. At Bluefrog, for example, we’ve seen responses of up to 5% on cold mailings in 2013.

They work because engagement requires time and space.

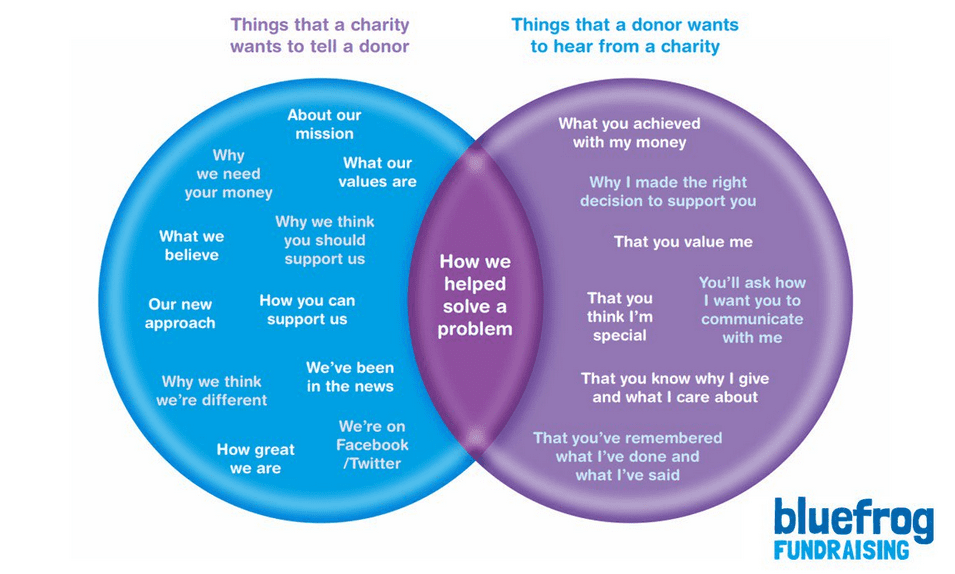

These techniques (when done well) allow you to not only present your case, but to also show the beneficiary as a real person and to give the donor what they need – a taste of the joy of giving (and perhaps even a chance to show off about what they have done).

These donors might not be the cheapest to recruit. They might require a great follow-up after recruitment. And they might not all become long-term supporters. But there are at least four good reasons why they are more valuable than a donor who only gave because they were interrupted.

They recognise the value of giving to you and give freely.

One of the problems with interruption techniques is that social pressure comes into play. Though this can be valuable in gaining that first gift, it can leave the donor feeling uncertain. It’s one of the reasons so many face to face cancellations happen in the first few days after recruitment.

They give a sum that matters to them.

Great fundraising isn’t just about asking for smaller and smaller sums until you reach a point where the gift is so small it doesn’t really concern your potential donor. Consider increasing the amount you ask for, rather than reducing it.

They are happy to share their address and contact details with you.

Donors who feel bombarded by charities who send inappropriate communications are not neccesarily in the right place to embark on a new relationship, even if it is going to be one that they might enjoy.

It’s one of the problems that we face with mobile giving.

Mobile donors tell us that they value the ease with which they can skip and stop. They also value the anonymity it offers them. It is ironic, but they value the fact that they can use their mobile to keep charities at arm’s length.

They are responsive.

Donors who are interested in your work, are far more likely to read your communications. If they aren’t interested, they won’t read anything you send them. And if they don’t read, they aren’t going to give.

In short, we need to make giving enjoyable for the donor again.

After all, that is our job. That is fundraising.