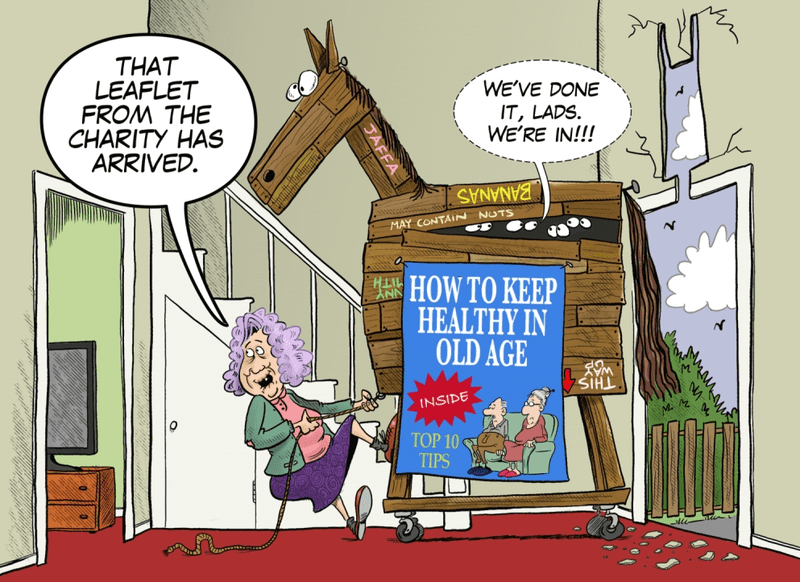

What is wrong with trojan horse fundraising?

There's a fundraising technique that's caught on in the last few years based on offering important information as a means to obtain someone's contact details.

You probably have seen the type of thing I'm talking about on TV or train ads. Rather than directly offer advice, the ads ask you to email or text in for an information booklet instead. Then, as part of the delivery or follow-up process, you are also asked to sign up to a regular gift.

Much of the approach is built on ideas highlighted in Robert Cialdini’s book, Influence: The Science of Persuasion.

Cialdini points out that as a general rule, people want to be consistent in their words and actions. If someone takes some form of action, it makes them feel uncomfortable if they fail to support it later on. In one study featured in the book, researchers spoke to people about road safety concerns and gave them a free postcard to display in their window that promoted safe driving. A few weeks later they went back to the same neighbourhood and asked participants to put a huge billboard up in their garden that featured the same message.

Compared to a control group (who were never asked to display the postcard), the people who put up the postcard were four times more likely to agree to have a billboard erected in their garden. All because they wanted to appear consistent in their commitment to promoting safe driving.

The fact that this approach of reciprocity and consistency is sometimes known as the Foot in the Door technique, should raise a few alarm bells. But that hasn't stopped it from being used by a number of high profile charities. Not least because it can generate significant numbers of prospects that can be spoken to outside the constraints of the current or upcoming fundraising legislation.

The fact that seems to be ignored is that Cialdini also highlights the point that this style of marketing often creates ill-feeling amongst those who have been exposed to it as they can feel they have been tricked (along with high attrition rates, this technique has also generated at least one complaint that has been upheld by the FRSB). He cites the fact that Hare Krishna fundraisers (who give away free books or flowers) actually stopped wearing their religious robes as they found potential donors would change paths to avoid an encounter. As he explains...

"Although the Society has tried to counter this increased vigilance by instructing members to be dressed and groomed in modern styles to avoid immediate recognition when soliciting (some actually carry flight bags or suitcases), even disguise has not worked especially well for the Krishnas. Too many individuals now know better than to accept unrequested offerings in public places like airports...It is a testament to the societal value of reciprocation that we have chosen to fight the Krishnas mostly by seeking to avoid rather than to withstand the force of their gift giving. The reciprocity rule that empowers their tactic is too strong—and socially beneficial—for us to want to violate it.

What's particularly concerning is the long-term implications of this approach. What might happen if people take the same approach to charities as they did to the Hare Krishna movement and started avoiding us? Any street fundraiser knows that many people already change their path or bury their head in their phone in an effort to avoid being asked for a gift.

But as we have seen, people tend to draw a distinction between fundraising and the core activity of a charity. If we start muddying the water to the point that people see a request for information is going to be accompanied by a telephone call asking for a direct debit, might that cause them to stop asking for information from the very charities they need help from in the first place?

It's a very high risk strategy that could well impact on organisations that don't use the approach along with those who do. And with the current high level of media scrutiny, the implications really worry me.

Fundraising is most effective when it is built on real connection and strong relationships. And I continue to believe that is what fundraisers should focus on building.

Just as there are good reasons why a donor chooses to give, there are other good reasons why they say no. We should overcome those barriers not through subterfuge, but by extolling the benefits of giving. I'm not convinced that ours is a profession that really needs to employ trojan horses to get our fundraising message across. But I may well be in the minority. What do you think?

Tags In

Related Posts

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

I was really angry when Anthony Nolan contacted me, signing up for their register is very different to wanting to give them money and yes the conversation started off about what a great thing I’d done signing up before they move it over to give us cash, hugely unimpressed; you expect medical records to be treated better.