How I learned to stop worrying and love financial overheads

The debate about the relaxation of rules controlling comparative charity advertising continues (the Fundraising Detective has the best links on his site).

Much of the discussion seems to be about the impact of charities putting the public boot into each other regarding things like admin and fundraising costs.

It's an important area. Donors really do want to know that their gifts are doing good (you can read more about this here).

But the fact is, few donors know anything about the real nature of "overhead" expenditure. Left to guess, they think the worst.

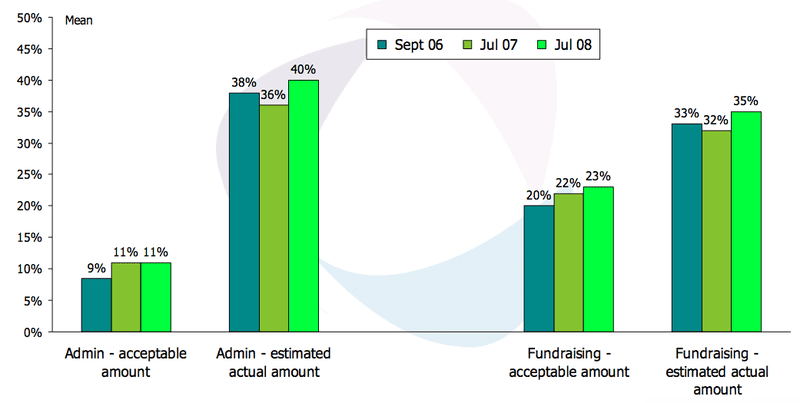

Research undertaken by nfpSynergy in 2008, asked what percentage of income was an acceptable amount to spend on admin and fundraising.

As the chart shows, people saw 11% on admin and 23% on fundraising as being reasonable.

They then asked respondents to estimate the amount that was actually spent on these areas and received a very different answer.

Those surveyed, estimated that 40% was used on admin and 35% spent on fundraising. That leaves just 25% to fund real work.

With figures like these, I'm surprised people give anything at all. If there is anything guaranteed to destroy trust, it's poor use of funds (even if it is just perceived). But still people give. It shows just how important the causes we tackle must be to our donors.

So what might happen if charities start to promote their admin and fundraising costs as a means of competitive differentiation?

To start with, most donors will probably be pleasantly surprised to see just how much money was being used at the sharp end. It might motivate a few more people to start giving.

It's what could happen next that worries me. We might see a Dr. Strangelovestyle 'admin' gap war with charities fighting to be the most efficient organisation in the sector. Donors might respond by starting to judge the worth of a charity purely on the basis of the size of their overhead.

That wouldn't be good. Cheapest is rarely best in any walk of life.

But I don't think many (if any) charities would embrace comparative advertising for three good reasons.

- It's a legal minefield. If you get your figures wrong you could be in real trouble.

- By talking about other charities, you are helping to advertise your competitors.

- If you can't promote your charity on its own merits, maybe it's not worth promoting.

But what this debate does highlight is the need to talk about "overheads" before others force us to do so. If we are worried about people on the inside of the sector raising these issues, what might happen if this was picked up by those on the outside?

Jeff Schreifels made a comment on this blog a few weeks ago about the position in the US, where watchdog groups perpetuate the belief that low overhead = better charity and the problems this has created.

He makes the point that we need to encourage donors to judge us on the results of our work, not on simplistic financial indicators.

But this means making a commitment to telling donors what their gift has helped achieve. And I don't mean producing standard broad brush newsletters and annual reports that talk about the general work of the charity.

To do this effectively we need to engage, involve and trust donors. And above all, show them one very important fact:

Overhead expenditure is not there to burn up money. It is there to make donations go further.

By changing our own attitude we could radically change those of our donors too. The nfpSynergy research shows we have a receptive and understanding audience and in testing at Bluefrog, we've found the more we share and the more that we involve donors, the more money we actually raise.

All this obviously depends on charities being able to justify their expenditure to donors, but if a charity doesn't have the physical results required, it might not have much of a case for ongoing support either.

Tags In

Related Posts

4 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

Mark thats a great addition to this debate. I think you are right in what you are saying (although Im not sure I would worry about name checking another charity as it may advertise their cause, I should be confident enough in what I do not to worry about that!).

It all seems to come down to Impact doesnt it and how we demonstrate that. I think thats what we all need to be working on. Let’s move away from the percentages and ratios debate. Lets face it which charity has a better impact, the one that spends 2 million and raises 10 or the one the spends 4 million and raises 15. On paper the first charity has better ratios, but the second charity actually has, net, more to spend on making an Impact.

Interested to see others thoughts on this debate.

Great post

Think you’re spot on Mark and agree with Conor’s point about impact, though if you’re demonstrating impact, surely it has to be against some benchmark or other organisation?

I suppose in some ways it brings me back to one of my high horses – how do we grow the overall pool of philanthropic giving and how do we overcome the ‘overhead’ myth that people have?

You’re right that individual charities can steal a march on competition by engaging, involving and trusting their donors, but personally I’d like to see the whole sector embrace this so it becomes the norm rather than the exception.

Hi Conor and Craig

Impact is of central importance though I’m not sure if benchmarking is needed.

If we can demonstrate to a donor that their gift has made a worthwhile difference we’ll have cracked 90% of the problem.

What frustrates me is that so many donors who take a first dip in the world of charity come up disappointed. Poor treatment by one equals poor treatment by all. Turned off, they turn their back on the sector.

Great fundraising is remarkable, wonderful, engaging and life-affirming. By exposing people to the work of charities who believe in this approach we will exapand the overall pool of donors.

Our only trouble is that we still have a long way to go to convert the sector to this way of thinking.

Thanks for reading. Keep up your great work.

Mark

I couldn’t agree more. We’ve allowed ourselves to get hamstrung with debates about admin and fundraising costs together with ratios which don’t help charities communicate how they change the world to their supporters and donors. And it’s that change that lies at the heart of what we’re about and which inspires commitment.