The tragedy of the commons

I studied development studies at university (at UEA) where as fresh young undergraduates we were introduced to Garret Hardin‘s concept of The Tragedy of the Commons (first published in Science magazine in 1968).

Hardin described a situation where a group of livestock owners share a pasture which can only support a finite number of cattle. But in order to maximise their personal benefit from the land, each owner increases their herd size whenever possible, worrying that if they don’t take advantage of the land they might ‘lose out’.

The result is that the number of cattle gradually increases to the point that the animals actually get thinner and start to die as there isn’t enough food to go around. Eventually the land becomes so degraded that the topsoil is blown or washed away and the once lush grass turns to scrub.

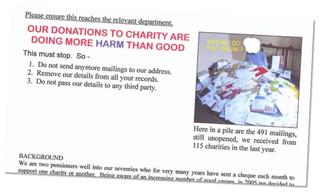

I was reminded about this a week or so ago when the Fundraising Detective featured a letter from a donor that pointed out that he, together with his wife, had received 491 mailing packs from 115 charities in the previous twelve months. That’s pretty much ten packs a week landing on their door mat!

I was reminded about this a week or so ago when the Fundraising Detective featured a letter from a donor that pointed out that he, together with his wife, had received 491 mailing packs from 115 charities in the previous twelve months. That’s pretty much ten packs a week landing on their door mat!

Craig summed up the impact of this approach…

“when you look at the whole (and I’d guess there are thousands of other donors receiving similar volumes of mail) it is simply unjustifiable and unsustainable in the long term. By continuing to act in this way, good causes risk driving donors to extinction by completely turning them off donating and alienating the very people who are happy to give.”

But it isn’t just mail. There are also the telephone calls, the knocks on the door, the face to face fundraisers in the street and the text messages on our mobile phones. Then there are the ads on the television, in the newspapers, on the radio, at the cinema, online and on billboards.

If our pasture is the population of donors, it would appear that fundraisers are some of the worst kinds of industrial farmers who are only managing to keep the grass growing by using ever more fantastic technology to eek out the last remnants of generosity from those upon whom we depend.

Even with the the massive potential of the web, with all the opportunities it offers us to engage and inspire, most innovation is often nothing more than another variant of the donation form.

So what should we – as fundraisers – do?

We can’t just stop asking for help. And if we change our approach, we don’t have to. But I agree with Craig that we can’t continue like this. We need to stop the more egregious examples of bad practice that turn donors off.

And in their place, we should perhaps adopt some of the techniques used by the more sensible herders who decide to effectively manage a finite resource.

Remove unproductive members

That means that you must stop repeatedly asking people for support when it is obvious they are never going to give to you.

This can be achieved by using our data intelligently. ‘Knowing the donor’ is central to any good fundraising operation. And when you have too many donors to get to know individually, it’s important that you use data so you can identify your best and worst prospects.

The result is less unwanted mail and less pressure on the collective population of donors. Some might say it’s an expensive solution to employ an agency to manage your data. But when you use data effectively you reduce your mailing (or calling) quantities and costs. You also increase your income by improving your relationship with those donors who actually will give.

You’ll be abe to identify the people who are most likely to convert to a regular gift, who will respond positively to your appeals (and at what time) and who might actually be interested in leaving you a legacy. You’ll also be able to identify those people who are likely to put your mailing in the rubbish and avoid upsetting them in the first place – and that does every other charity a favour as these donors are likely to be more suited to supporting other charities (it might sound crazy, but it’s true).

This is covered within the IOF Code of Direct Marketing Fundraising Practice, but how many complaints have been made about poor data management? Not many.

Protect and care for the calves

Younger donors who aren’t direct mail responsive tend to have some of the worst experiences of giving to charity. They get signed up to a direct debit on the street and… well that’s it really. Some might get a few appeals asking for more money or newsletters telling them how great the organisation is but the result is that the best part of three-quarters of these youngsters cancel their gift in the first year.

So rather than give them the treatment that works for the mature members of the herd, we should focus on reminding them that they are part of an important and valuable movement. We should give them the materials to demonstrate that fact to others. And don’t think that producing more leaflets explaining why you need the money is going to work. Focus instead on providing regular communications and engagement devices that enhance their self-image. You should also try to give them routes to support you in non-financial ways as well.

That way, when younger donors move into the ‘giving age’ they will have a far more positive impression of the whole charitable sector.

For more on why younger donors give, you should read the millenial donors report (PDF) from Johnson Grossnickle Associates and Achieve.

Oh, your older donors would also love the same treatment. It works on them too.

Keep the land free of pollutants

In a pasture, everything from plastic bags to buttercups can hurt cattle that eat them, so we need to ensure our environment is protected from the sector’s equivalent of poinsonous plants and rubbish. This is something that the IOF codes of practice don’t include – irrelevant and self-obsessed creative approaches. Work that fails to take into account the needs of the donor has a slow but insidious effect as it makes fundraising an unpleasant experience.

Forget about the few mailings containing umbrellas that get sent out, it’s the over-designed packs full of statistics and jargon that rattle on about how great the brand is is that worry me.

Provide care for the injured

If a cow is injured it will need some individual care. It’s the same with donors when they are mistreated. And that’s when you should listen to them and respond. Craig was the first charity representative to call the very generous donor who wrote to him about his experience of charity mailings (even though the charities on the list include some very illustrious names).

Listening requires a change in mentality – but it works. Why not start by asking your donors if they are happy to receive appeals from you? Those that don’t want them are probably never going to give to you anyway.

Care USA send a customer care piece to new donors as part of their welcome and regular giver conversion programme. It offers donors the opportunity to choose how often they receive communications. Less than 0.1% of donors asked to opt-out completely whereas the conversion rate to monthly gifts increased by 16%.

The fact is that there aren’t that many people in the UK population that sign up to direct debits or respond to mailing packs. If we want to keep their support (and add to their numbers), we need to make giving to charity more rewarding and enjoyable. And after reading Craig’s post, maybe that’s what the IOF should be focusing on the next time they review their codes of practice.

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?