The A to Z of writing fundraising appeals (Part 3)

Here comes the final part of Steve Lynch’s guide to writing great fundraising copy. If you’ve missed the earlier posts, you can find part one here and part two here. We kick off today with M.

M is for Monkey

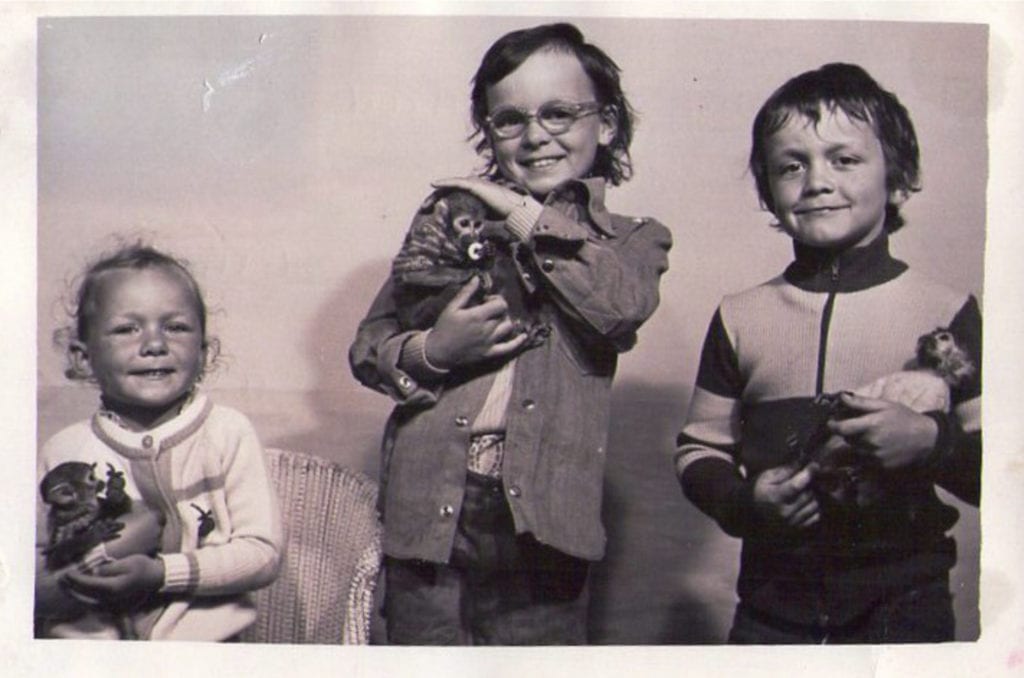

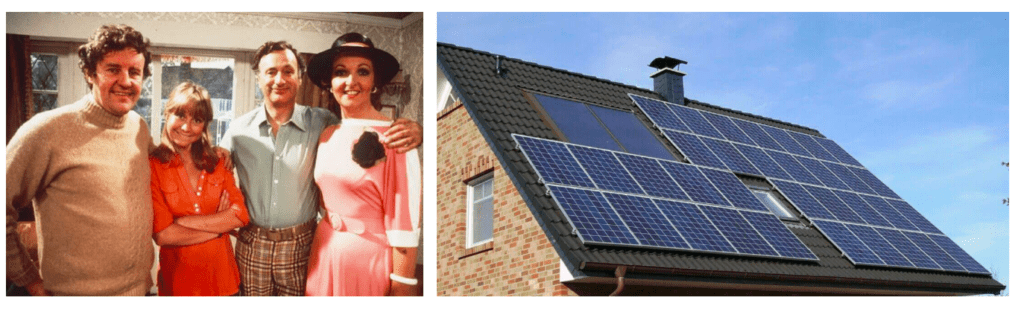

Do you notice anything odd about the monkey I’m holding (I’m the one on the right)? Look closely. Yes, that’s right, it’s a bloody fake.

In the 70s at the seaside you’d often see men (it was always men) who would, for a small fee, take a photo of you with exotic animals. And I loved monkeys, so begged my mum to get the photo taken. Except the bloke only had two monkeys and there were three of us and you can see what happened next. No wonder my sisters look so happy, they’ve got proper monkeys!

Am I still bitter? You bet I am. But the relevance to fundraising is the old cliché that a picture really can tell a thousand words.

As a writer you need to always bear in mind how donors might react to the pictures they’re seeing. And your words have to be in harmony with the images. So if, for instance, you only have one pic of a case study and they’ve got a big beaming smile on their face, the content, tone and approach of the copy has to reflect that. If you are featuring a pic where a case study looks hungry or vulnerable, it will jar if you then have an upbeat tone talking about the wonderful transformation your charity was behind.

You should never start a letter, or email or whatever, without knowing what pictures people might look at when they read it. Look at them closely and ask yourself how the copy and images are going to work together, rather than fighting against each other – like me and my sisters did about three seconds after the photo was taken.

M is (also) for Mum

While the final arbiter of the success or failure of any fundraising campaign is the balance sheet, results can take ages to come in. So for the impatient amongst us I’d like to suggest an alternative, although not in my case foolproof, means of determining whether your latest campaign is working as hard as you’d like it to.

Show it to somebody outside of the industry whose opinion you really respect, or if like me you are still fighting a desperate and probably vain battle for parental approval, you could show it to your mum.

If yours is anything like mine, I’d suggest only showing her materials in the public domain (inserts, press etc.). The simple reason being that despite years of my explaining that lots of people want to receive Direct Mail, and value their relationships with the charities they support, my mum still insists that I write ‘begging letters’ for a living.

I don’t think my mum could ever be described as a typical anything, and she certainly isn’t a typical charity donor (she’s half way between a Dorothy Donor and a Baby Boomer – does that make her a Doomer?). But she reads the papers (OK, she does the crossword and checks what’s on telly, but you know what I mean) and has a sharp eye for any contrivance or, as she would put it, ‘old flannel’.

So in many ways, she’s a one-woman, extremely cost-effective focus group. If you suspect yours might be able to offer you the same service, can I suggest the following, completely unscientific, scale for assessing whether your fundraising is really hitting the mark?

If she says “Mmmm. Lovely” then hands your lovingly crafted insert or press ad straight back to you and quickly changes the subject, its time to go back to the drawing board. 1 out of 10.

You’re on the right tracks when she takes a while to read it, has to flip back pages a couple of times to get her bearings and says at the end “Oh yeah, I get it now, that’s quite clever”, but you could do better. The proposition’s got a bit muddied somewhere along the way. 2-4 out of 10.

If she says, “Who’s my clever little boy” (I’m 51) and offers to rustle up a quick bacon sandwich, you’ve definitely got something. 5-7 out of 10.

When she asks, “Blimey, where’d you get your brains from?” and does a quick ring round to make sure sisters, aunties and assorted acquaintances get to see your piece, and are left in no doubt as to whose child was responsible for it, you know you’ve produced a winner. 8-9 out of 10.

But you know you’ve produced the best, possibly award-winning work, when despite your pleading and protestations, she insists that, “You never did that,” and flat out refuses to believe that you could possibly have been involved with the creation of such a moving or inspiring piece of work*. 10 out 10.

*This doesn’t happen very often.

N is for Newspapers

A couple of years ago I met up with an old colleague whom I had ‘trained’ to be a copywriter. Now very successful, he said that I had given him the best piece of advice he’d ever received on his path to copywriting superstardom. Can you guess what it was? I know I couldn’t, I’d completely forgotten that I’d ever said it.

My colleague said that the career-changing advice was simply to ‘read a newspaper every day’.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, and I think the reason the advice worked for my colleague is because it gave him something that fundraisers are always looking for – an insight into the mind’s of their supporters.

People’s outlook and ideas are formed, in the first instance, by personal experience. But after that how we understand the world doesn’t materialize from thin air, it comes from the news media and the culture around us. All of the issues charities deal with, whether it’s poverty, health, education, homelessness, development or palliative care are, in the good newspapers, covered extensively and often. How the papers discuss these issues will almost certainly be reflected in your donor’s understanding of them. Reading a paper, every day and not online (its too easy to miss content), will help you understand how your donor’s understand you.

A brief example. A few years ago a paper ran a big expose of how aid was not getting in to help people in a conflict-affected area. Nobody in the charity had seen it (they were all quite young and didn’t read the traditional news media), so when the brief for an appeal came over it wasn’t mentioned – even though the donor profile told us they were predominantly readers of the paper the article appeared in.

So if I hadn’t read that article, we’d have asked people to fund aid that they had just read wasn’t going to get to the people who needed it!

Instead the appeal focusesed on getting the aid in and, alongside a petition, asked for donations so that the charity could get the aid they bought to people at the first possible opportunity. At the time, the appeal was the charity’s most successful ever.

So read the Guardian, the I, or The Times and watch Channel 4 News or Newsnight. Maybe even occasionally listen to Radio 4. Your donors do.

N is (also) for Ngrams

This is brilliant.

https://books.google.com/ngrams

Google has scanned I don’t know how many million of books, and developed a tool which tells you how many times words appear in them over time.

Its great for finding out what are ‘new’ or voguish words. If you check a word and it hardly appears before 1970, chances are it will be unfamiliar to your donors. I suggest searching for ‘empower’, ‘sustainable’ or ‘access’.

With the possible exception of new nouns, if your donor didn’t grow up using a word its odds on it will sound strange to them – and could make your organisation feel distant and corporate. If you’re thinking of using a word that shows a steep increase after 1970, I’d suggest its time to go back to the Thesaurus.

O is for Orwell

If you can forgive him for the gendered pronouns, anybody aspiring to be a writer should familiarise themselves with this brilliant advice from George Orwell, published in his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language.

A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: 1. What am I trying to say? 2. What words will express it? 3. What image or idiom will make it clearer? 4. Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?

And he will probably ask himself two more: 1. Could I put it more shortly? 2. Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?

One can often be in doubt about the effect of a word or a phrase, and one needs rules that one can rely on when instinct fails. I think the following rules will cover most cases: 1. Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print. 2. Never use a long word where a short one will do. 3. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out. 4. Never use the passive where you can use the active. 5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent. 6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

P is for Polemic

Historically, some on the left haven’t been great fans of charities and philanthropy. George Orwell, most famous for being the subject of the previous section, wrote: “However delicately it is disguised, charity is still horrible; there is a malaise, almost a secret hatred, between the giver and the receiver.”

In the extract below, from Friedrich Engels’ The conditions of the Working Class in England (1845), the author asserts that charities exist only to assuage the guilt of ‘luxurious bourgeois’ who directly profit from the terrible conditions of their workers, which they occasionally give a few pounds to alleviate.

When you read the letter to the Manchester Guardian he reproduces, you might understand why he was so angry.

The piece is a great example of polemical writing – something I believe we see all too rarely in the charity sector these days. Engels saw charitable giving as a tool of his enemy, and if your cause has an enemy, such as the fossil fuel industry, wildlife trade or plastic polluters, a good old-fashioned polemical tirade could be the perfect way of rousing people into action behind your cause.

Let no one believe that the “cultivated” Englishman openly brags with his egotism. On the contrary, he conceals it under the vilest hypocrisy. What? The wealthy English fail to remember the poor? They who have founded philanthropic institutions, such as no other country can boast of! Philanthropic institutions forsooth! As though you rendered the proletarians a service in first sucking out their very life-blood and then practising your self-complacent, Pharisaic philanthropy upon them, placing yourselves before the world as mighty benefactors of humanity when you give back to the plundered victims the hundredth part of what belongs to them! Charity which degrades him who gives more than him who takes; charity which treads the downtrodden still deeper in the dust, which demands that the degraded, the pariah cast out by society, shall first surrender the last that remains to him, his very claim to manhood, shall first beg for mercy before your mercy deigns to press, in the shape of an alms, the brand of degradation upon his brow. But let us hear the English bourgeoisie’s own words. It is not yet a year since I read in the Manchester Guardian the following letter to the editor, which was published without comment as a perfectly natural, reasonable thing:

MR. EDITOR,

For some time past our main streets are haunted by swarms of beggars, who try to awaken the pity of the passers-by in a most shameless and annoying manner, by exposing their tattered clothing, sickly aspect, and disgusting wounds and deformities. I should think that when one not only pays the poor rate, but also contributes largely to the charitable institutions, one had done enough to earn a right to be spared such disagreeable and impertinent molestations. And why else do we pay such high rates for the maintenance of the municipal police, if they do not even protect us so far as to make it possible to go to or out of town in peace? I hope the publication of these lines in your widely circulated paper may induce the authorities to remove this nuisance; and I remain,–

Your obedient servant, “A Lady.”

There you have it! The English bourgeoisie is charitable out of self-interest; it gives nothing outright, but regards its gifts as a business matter, makes a bargain with the poor, saying: ”If I spend this much upon benevolent institutions, I thereby purchase the right not to be troubled any further, and you are bound thereby to stay in your dusky holes and not to irritate my tender nerves by exposing your misery. You shall despair as before, but you shall despair unseen, this I require, this I purchase with my subscription of twenty pounds for the infirmary!” It is infamous, this charity of a Christian bourgeois! And so writes “A Lady”; she does well to sign herself such, well that she has lost the courage to call herself a woman! But if the “Ladies” are such as this, what must the “Gentlemen” be? It will be said that this is a single case; but no, the foregoing letter expresses the temper of the great majority of the English bourgeoisie, or the editor would not have accepted it, and some reply would have been made to it, which I watched for in vain in the succeeding numbers. And as to the efficiency of this philanthropy, Canon Parkinson himself says that the poor are relieved much more by the poor than by the bourgeoisie; and such relief given by an honest proletarian who knows himself what it is to be hungry, for whom sharing his scanty meal is really a sacrifice, but a sacrifice borne with pleasure, such help has a wholly different ring to it from the carelessly-tossed alms of the luxurious bourgeois.

By the way, the attitudes expressed in the letter are still alive and kicking today. A few months ago I overheard a diner at a nearby table complain about the injustice of having a new ‘social housing’ development built near her five bedroom house, and having to watch ‘all sorts of riff-raff traipse by’. Poor woman! We had a discussion...

Q is for Queer Ideas

I have a visceral aversion to crawling, bootlicking and sucking-up of any kind. So when I advise you to read Mark Phillips’s blog, you can be absolutely sure it’s not because he’s my boss. It’s because, and believe me it pains me to say this, its good.

Mark’s blog is called Queer Ideas and in it he does something very important. He asks why?

Let’s be honest, the fundraising industry can be a little complacent and lots of us do things purely because everybody else does. Like asking for a £3 a month Direct Debit or chasing younger, probably non-existent, donors. Mark challenges the received wisdoms and digs out the evidence and statistics that help us understand what really works and what doesn’t.

And at Bluefrog we have a revolutionary way of unearthing our donor’s motivations, interests and passions – we talk to them. A lot of Mark’s posts are about how we should learn from what our donors tell us.

All fundraisers, and particularly anybody who has responsibility for a fundraising budget, would do well to read it.

R is for Repetition

The problem with advice, is that sometimes people listen to it.

Take the oft-repeated adage that fundraising copy should embrace repetition. Say it once, say it twice then say it again, if you really want your message to hit home.

I’ve got no problem with that, except when it’s taken literally. As in repeating the exact same bloody phrases.

You can state your proposition as many times as you need, but always try to find a different way to say it, or to contextualize it. Repeating the exact same thing isn’t compelling, it’s annoying. There’s a reason the word ‘repetitive’ is very nearly a synonym for ‘boring’.

Another misconception about repetition is that you should never use the same words within the same section of text. I’ve had people tell me I shouldn’t use ‘the’ twice in the same paragraph! Repeating prepositions is absolutely fine, and sometimes repeating the same words, even within a sentence, can be a powerful way of emphasising or underlining an idea. Like here:

“We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.”

Joan Didion, from Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968).

S is for Slogan

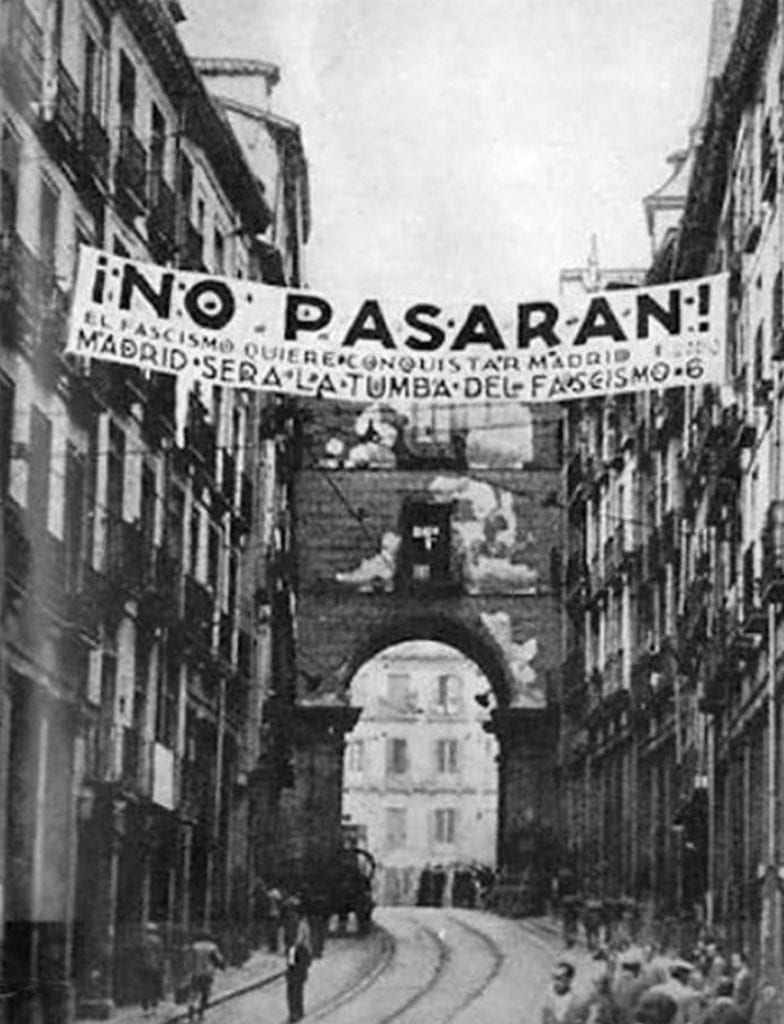

In 1936, Republican Madrid was under siege by Fascist troops led by General Franco and armed by Hitler’s Germany.

In an attempt to rally the Republican forces in defence of their capital, Communist leader Dolores Ibarruri Gomez (known as La Passionara – the Passion Flower) gave a famous speech that culminated in a call to arms and slogan that perfectly encapsulated her determination to defend the city at all costs:

No Pasaran (They shall not pass)

A great slogan is a truly powerful thing, and as well as helping you drive back fascists, could give your fundraising campaigns a huge boost. It can be built around a final aim, or target, or aspiration, and helps to focus people’s minds on what you are trying to achieve while allowing supporters to feel part of something bigger.

But a good slogan is really, really hard to come up with. Sometimes, the less words you have to play with, the more difficult it can be to find the right ones, and campaign slogans have to be short.

My advice would be to start by writing down anything that comes into your head. Maybe stop when you’ve got to 100 possible slogans. Then use a thesaurus to see if changing any of the words for a simile would make any of your attempts better. Then whittle it down to say, 20. Then show other people and ask what they think.

When you’ve got your winning slogan you’ll need to google it to make sure nobody else has used it in the last few years. Then you will, almost certainly, need to start again. Sorry, but I did say it was hard.

Here's just a couple of the slogans we’ve developed at Bluefrog:

This must have been OK, the campaign’s raised over $25million so far.

T is for Tone of voice

Does your charity, or the one you’re writing for, have an official Tone of Voice? If it does, I bet I know what it is. It’s almost certainly both compassionate and passionate and odds on its about action and getting things done. You probably also want to convey that you do things together, as a team.

Was I right? Probably, and that’s because all official charity Tones of Voice are, essentially, exactly the bloody same. Of course your TOV is compassionate, you’re a charity. It’s staggering to think how much time and money has been wasted developing documents that describe a ‘unique’ TOV when every single charity in the world could just say, ‘we care a lot about the thing we exist for, and we’re quite nice’.

So my advice for anybody writing or reviewing copy is simple – ignore what your charity’s TOV is supposed to be. Write in the TOV that your donors want to hear. Be conversational, friendly, respectful and interesting.

Sometimes you do need to do a bit more, but that will be determined by your letter’s signatory or your cause rather than a TOV statement dreamed up by a corporate brander.

So when I’m writing for military charities from, for instance, a Major General, I channel Trevor Howard in a WWII film. If I’m writing about children, I imagine they’re mine. If I’m writing about a great injustice, I get angry.

After you’ve written it, read your letter out loud. Does it sound like the person whose signature is at the bottom wrote it? Then you have the TOV.

U is for Urgency

Urgency in appeals is always good. We know that it gets results and that, even with the best intentions, if people don’t respond straight after reading an appeal they’re likely to forget, or put it to the back of their mind. But creating urgency can be difficult, as this conversation shows:

Client Services Colleague: We got the feedback from the client through and they want the pack to have much more urgency.

Me: OK. Do we have a deadline when they need the money by? Perhaps they need to allocate funding or something?

Client Services Colleague: No

Me: OK, can we say there will be some sort of consequence if people don’t give now? For good or bad?

Client Services Colleague: No.

Me: It will be tough then, but maybe there’s some sort of anniversary or event we could hang it on, you know, ‘return your gift by May 12 in time for the 20th anniversary of the first time we did this’, something like that?

Client Services Colleague: Sorry. No.

Me: What am I supposed to do then?

Client Services Colleague: They said you should use more urgent words.

I’ve had conversations like this many times and it doesn’t get any easier to make the case for giving more urgent, when there is no compelling reason I can give donors for it being so. But in the absence of a target, deadline, or consequence of not giving, there are some things you can do.

Highlight a growing need. If more people than previously need your charity’s help, you can impart a pressing need by telling donors.

Say ‘today’ a lot. Remind people to give now. You could even tell them to put the Freepost envelope in their bag or pocket, so its there next time they pass a postbox.

The sooner we get it. Tell people that the sooner you get their gift, the sooner it will help the people or cause they care about.

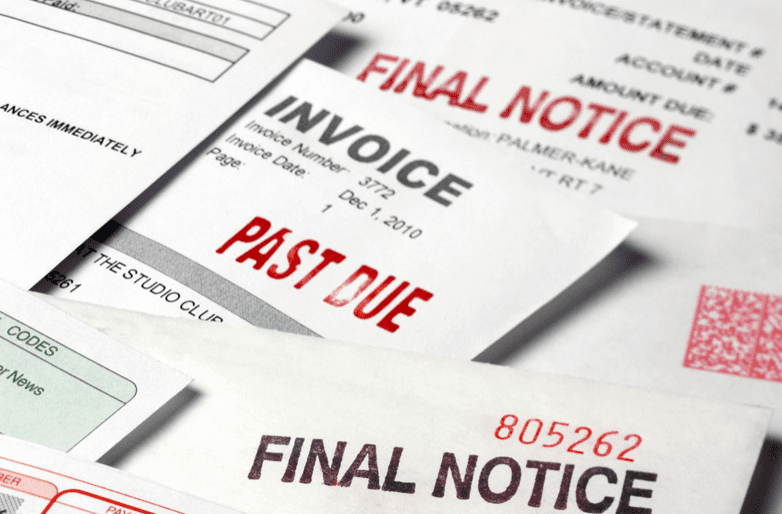

URGENT: Use the actual word URGENT. Maybe put it in a big red stamp. Put it on the reply form and BRE as well. Don’t bother looking for synonyms that say URGENT better, I’ve checked and there aren’t any.

P.S. Younger readers may not be aware that donors will probably associate red stamps on envelopes with one of these.

I think the Gas and Electricity Boards were hoping to shame people into paying on time, but it didn’t work. Where I grew up, nobody even looked at a bill until they got the ‘Reddy’.

V is for Variables

Using variable copy, where we individually laser details of a donor’s relationship with a charity into a letter, can be a powerful tool in the hands of a fundraising copywriter. It allows us to show supporters that we know them and talk to them as an individual, rather than just the proverbial cash point.

We all do it in most of our letters to donors, but most of the time we do it badly. Variable copy is all too often perfunctory, generic and dull. It’s easy to fall into the habit of writing variable copy because we feel we have to, rather than thinking about what it can achieve.

Some of the time this happens because the data isn’t very good and its difficult to say much at all, so we end up writing catch-all variables that don’t really achieve very much. Like:

<Thank you so much for your <regular gifts> which do so much to help people affected by (whatever it is).>

But even if we can’t tell much about a donor from the data, we could still give it more oomph.

<Every month, because of your regular gift, somebody affected by (whatever it is) will have somewhere to turn to; they won’t have to face (situation) on their own. Thank you so much for your wonderful commitment to being there for people like (case study name).

And when we do know more about donors from the data, we should always express not just gratitude, but impact. If we know how much they gave, and how much the thing we asked for costs, we should be able to write variables like this:

<Your gift meant <x> young people could spend a night safe and warm with us, away from the dangers of the street. Because of you those <X> young people, who may have experienced terrible trauma and abuse, will have had a hot meal, a shower and a good night’s sleep – maybe their first one in weeks. Your generosity will mean those <X> young people will no longer feel so alone, they know they have <our charity> and they have you. Thank you <Mrs Sample.>

Obviously that takes up more space than a perfunctory or generic thank you. But it’s worth it.

W is for Words of wisdom

“I write as straight as I can, just as I walk as straight as I can, because that is the best way to get there.”

HG Wells

It’s a good idea to use fewer words, but that doesn’t mean you could get the same level of responses by sending donors a compliments slip rather than a four-page letter. It means, as Wells suggests, that you should make your argument, ask and points economically, using as few words to get there as you can.

X is for £XX

Thanks to the technological miracle that is modern printing, when I’m writing copy for a charity’s existing donors, I don’t have to type out how much money I’m asking for. In the word doc I put:

<£XX>

and the amount is lasered in, depending on the donor’s giving history. Its important to remember, however, that one person’s <£X> is another person’s <£XXX,XXX>.

You should write the copy differently, depending on what’s going to replace the XXs. For instance, for lower value donors, who give under £10, you might write:

Your gift of £XX will give another family like Alex’s seeds to plant this year, which means healthy food for the children and even a little left over to sell at market.

If the £XX is going to be replaced by £200, you will need something a bit different.

Your gift of <£XX> will mean 10 families like Alex’s have seeds to plant this year. Their children will have food to eat and they’ll have a surplus to sell so they can pay school fees. Your generosity could help lift an entire community out of poverty, for good.

Y is for You

No prizes for guessing what Y was going to be. This is, after all, about fundraising.

But instead of being the millionth person telling you that YOU is the most important word in fundraising copy, I though I’d talk about YOU the reader of this blog, somebody who potentially might want to work as a copywriter, or who might occasionally need to write donor communications. Here’s a list of things YOU might need to do write to donors successfully (apologies if some of these are covered in previous posts – this A to Z thing gets hard towards the end).

YOU will need to give a f**K about the cause you’re writing about. Without it, copywriting is hard work and nobody wants to do that.

YOU will need a good grounding in English. Sentence structure, punctuation and grammar aren’t things you can pick up overnight, however hard you work at them. If you don’t love words and language, you’re probably not going to be good at creating them.

YOU will need to do your research – into both your cause and your audience.

YOU will have to write several drafts before you get it close to something that’s good enough.

YOU will need to learn from people who’ve been doing this for a while. Master the techniques but then, crucially, challenge them to see if you can do something better.

YOU will need a thick skin. To write good copy, you have to put a lot of yourself into it, so when people don’t like it, it can hurt.

Y is (also) for Youth

To return to a point I made in an earlier blog, it’s key to remember that you are not your audience. You are almost certainly much, much younger than them. To illustrate why this knowledge should influence every word you write, I’ve put together this chart showing how some common charity words or phrases might mean something completely different to somebody in their 70s.

Collection Box

Regular

Sustainable

Z is for Zinger

If you read F for Feedback (Bad) you will remember that I’m not great when people criticise my copy. And when they do, it really isn’t going to help if they come out with a Zinger like this:

Please check the use of apostrophe’s throughout the copy document.

The context is revealing. This person didn’t feed back like other clients. They put theirs in an excel spreadsheet that had seven columns in it so various people from across the organisation could have their say. There were 186 lines. So that’s 186 comments, x7. On a pack that consisted of just an envelope, letter and don form.

Over complicated sign-off procedures like this are appeal killers. Nothing good can survive a process involving so many diverse and often opposing opinions.

You can’t write a fundraising letter by committee. It just doesn’t work. The more people you involve in sign-off, the more you dilute your message, the more your communication becomes about box-ticking, rather than addressing the concerns of the real human beings you’re supposed to be talking to.

The great David Ogilvy had a thing or two to say about how highly he valued criticism from non-qualified outsiders (see no. 12).

But still it goes on…and still we, as a sector, end up putting out communications that aren’t anywhere near as good as they could be simply to appease the foibles, or massage the egos, of people within our own organisations.

So if you work for a charity please, for the sake of my sanity at least, try to streamline your sign-off process. Only good stuff can happen as a result.

Z is (also) for Zzzzzs

My first copywriting job was in financial services and I loathed it. I couldn’t sleep at night because I felt guilty for persuading people to get credit cards, invest in dodgy ISAs or take out loans they couldn’t afford. When people asked me what I did for a living, I often lied. I told myself I had to pay the rent, but I was ashamed.

Perhaps the best thing about writing for charities is that I can go to sleep at night knowing that, in however small a way, I’ve spent my working day helping to change the world for the better.

Writing for charities can be frustrating (see about 10 of my previous posts) and of course it comes with the same day-to-day niggles and nonsense as any other job. But when all’s told it’s not a bad way to make a living. At the very least, to borrow from the Hippocratic Oath, it’s very likely that you will ‘Do No Harm’. Sometimes it’s fantastic. Without wishing to sound smug, when I see a new press ad I’ve written, or get a mail pack through the door that I’m proud of, it feels great.

So if anything I wrote in my previous posts might have put you off pursuing a career in copywriting or fundraising, I apologise. I was just having a moan. You should go for it. Good luck.

Tags In

Related Posts

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

[…] Lastly, DO NOT MISS Mark Phillips The A to Z of Writing Fundraising Appeals. Find the entire series here, and here, and here. […]