Why giving to charity can be like buying a Polaris submarine

My dad was a printer. When he worked night shifts on the national newspapers I always went to bed very excited. That's because I knew he'd come home with a gift for me. As soon as I woke up, I'd rush downstairs to find a toy car, a model plane or an American comic sitting on the kitchen table.

The American comics were perhaps the most exciting. Unlike British comics, they had glossy covers and featured exotic characters like Richie Rich or Casper the Friendly Ghost.

As well as the stories, they were packed full of ads that featured the most amazing products that seemed perfectly designed to separate a seven year old boy from south-east London with his hard earned pocket money.

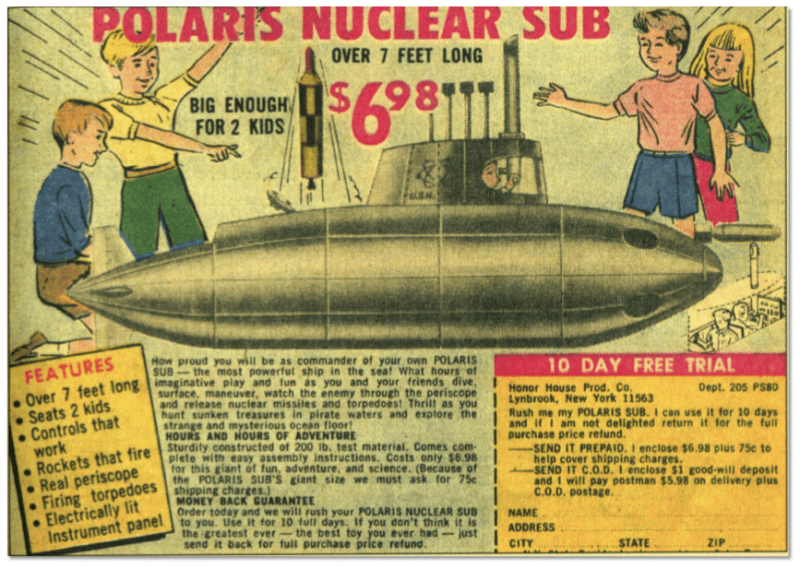

The choice was mouth watering. Within a few pages you could find 'Real' X-Ray spex, instructions how to build a 'working' laser pistol, a 100 piece plastic soldier set with tanks, ships and planes packed in a footlocker, or the ultimate toy - a Polaris nuclear sub - that at over 7 feet long was "big enough for 2 kids".

To my young mind, this submarine was fully functional. The advert described it as the "most powerful ship in the sea". You could actually release nuclear missiles and torpedoes (if you were so inclined). And encased in "200 lb test material" you'd surely be safe at the bottom of the ocean.

All this was available at $6.98. The only thing that stopped me from buying one was the fact I had no idea how to get hold of a dollar money order.

Instead I was left imagining the thousands of Polaris submarines containing children of my age that were undoubtably a hazard to shipping all along the US coastline.

Instead I was left imagining the thousands of Polaris submarines containing children of my age that were undoubtably a hazard to shipping all along the US coastline.

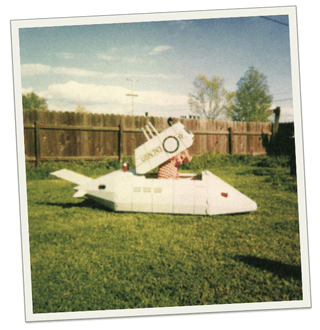

It wasn't until much later (after I met real Americans) that I found out that most of these toys were little more than cheap junk. The soldiers weren't a patch on our own homegrown Airfix variety and the submarine was actually made from cardboard. A mild drizzle would see it turn into a pile of sodden pulp. The fact that the missiles were fired by a rubber band would also mean that the world's population could sleep soundly knowing that a rapidly emptied money box wasn't going to bring about a nuclear winter.

If I had managed to get hold of $6.98 (plus 75c to help cover shipping charges) I'd have spent the weeks waiting for delivery in breathless anticipation only to be left with a huge sense of disappointment once the "best toy you ever had" arrived ready for assembly but not for a quick trip over to France from Hastings beach.

Such was the seductive power of the ad, even the fact I could get my money back wouldn't have erased the pain of the unfulfilled dream of sinking slowly below the browny-green waves of the English Channel in search of pirate treasure.

I'm a little older now, but I still have dreams. And, like many other people, I try and make those dreams come true by supporting charities. A cure for cancer, the end of poverty and prevention of animal cruelty are all on my list, but just like buying a submarine, the result of giving often leaves me feeling a little flat.

Instead of being invited to be part of something life changing, I get a polite and formal letter that informs me that my money has gone in to a big pot and will do something good, somewhere at some point in the future.

I'd like a little more than that. And when we see just how few people give a second gift in response to cash appeals, it looks like I'm not alone.

Fundraising isn't just about asking. If it was that simple, charities would be awash with money. It's about giving something to your donors that they need and value.

That doesn't mean simply telling donors what your charity does (yet again) in a welcome pack.

It's about grabbing the one chance when you are virtually guaranteed that a donor will open your communication and read it. You can then give them just what they want...

- Recognition for what they've done.

- The opportunity to demonstrate that fact to others.

- Authentic, personal treatment.

- A reason to smile (or cry).

If we do that, we'll find people will actually want to open our appeals. And though they might not get as excited as I did about the thought of my own personal submarine, it will go a long way to encourage a one-off donor to become a long-term supporter.

If you'd like to dig a little deeper into the world of comic book ads, this is a good place to start.

Tags In

Related Posts

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?

I would hate to think that any of my donors are as disappointed in us as I was in those Sea Monkeys!

I am troubled by the proclaimed goals of – insert ending social problem here –. I appreciate the big vision but I have yet to see an entire sector of charities pack it in because a social problem no longer exists.

I think being authentic, personal and specific about what a gift accomplishes is more effective than the “over promise, under deliver” of a grandiose vision.

Thanks Mark, for reminding us just how long the taste of disappointment lingers.

Mark, Great article. I always wondered what those submarines looked like.

My question to you is how do you suggest recognizing donors other than a polite thank you, listing their name in an annual report and/or premiums(which we don’t do). I’ve struggled with what to do for our donors to thank them and would love your input.