5 ways to screw up a brief

I've recently become a fan of cakewrecks. It's a blog that features pictures of cakes that have gone wrong. Poorly designed, inappropriate, creepy, ugly and just plain wrong!

The best are the result of misunderstandings and are great examples of what happens when there is a massive breakdown in communications.

Imagine this conversation (recounted on cakewrecks) for example:

(answering phone] "Cakey Cake Bakery, Jill speaking! How can I help you?"

"Hi, I need to order a cake for my boss. We have a photo of him playing golf that we'd like to put on it though - can you do that?"

"Of course! Just bring the photo in on a USB drive and we'll print it out here."

"Great, I'll bring it by this afternoon."

Later...

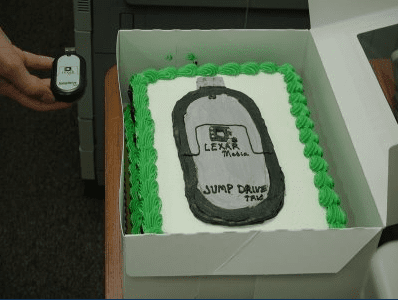

"Hey, Jill, what am I putting on this cake?"

"Oh, check the counter; I left the jump drive out for you there."

[calling from the back room] "Really? This is what they want on the cake?"

"Yeah, the customer just brought it in."

"Okey dokey!"

And the beautiful result was...

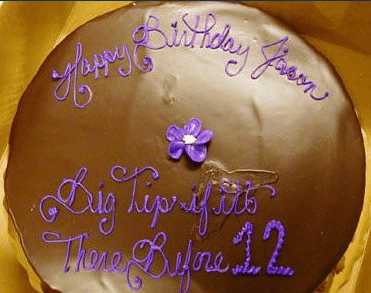

Or how about this one? it looks like it was a rush job. They had to offer a big tip to get it delivered by 12.

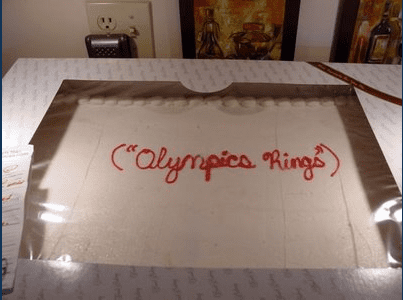

Or this one? I'll leave it to you to guess what the customer actually wanted on the cake.

All of them (and there are many more on the site) are examples of a misunderstood brief.

It's easy to blame the cake designer for being stupid. But I've seen plenty of briefs with a massive amount of room for error. It's one of the biggest problems an agency faces in developing creative work. It's why you need to give brief writing plenty of time and consideration.

But even then, there are 5 rock solid ways to screw up a briefing. Follow these rules and you are guaranteed to waste a huge amount of time and money.

1. Don't show the brief to the people who will sign off the creative work.

If the Chief Executive or the Head of Communications is going to be approving work, get their buy in to the brief – otherwise you have no one else to blame when they blow an idea out of the water for being 'off-brand'.

2. Define the target market as simply a broad demographic.

ABC1 women, aged 55+, living in the home counties means nothing. I know one donor included in this description who spends her evenings in S&M clubs swinging a cat o' nine tails. I know others who spend the same evenings sipping Horlicks and stroking their pet tabby.

When you talk about a target audience, describe them in human terms - what makes them laugh, what makes them cry, what they value and what they hate.

Steve Henry (from HHCL) always used to use the analogy of introducing people at a dinner party for defining customers (or donors). You try and find something that they are both interested in like hair crimping or football. Then you can leave them to get on with it, knowing they have something they can talk about. Try and define the things in your audience that brings them together (At Bluefrog, we call them hot buttons).

3. Put in a list of all your brand values or refer to a website that lists all the brand values.

Many charities have too many brand values. It is not unusual to have a list of seven or eight presented in a brief. A group of usual suspects might include: professional, trustworthy, innovative, creative, down-to-earth, experienced, outraged and caring. These are often supplemented with a number of other adjectives that describe tone of voice or personality (taking all three into account, I've seen brands that have over 40 adjectives linked to them).

It is all but impossible to effectively communicate more than two or three values in a communication. That's why many commercial products concentrate on trying to own just one or two. Maurice Saatchi called it "one word equity". A great example of this is: Volvo = safety

It doesn't matter how many airbags or how strong a roll cage a Mercedes has, Volvo still beats it on safety in the mind of the car buyer.

What you actually do when you offer a creative team a long list of adjectives in a set of brand guidelines, is abdicate choice. And by doing so, you increase the chance of failure.

If a creative team concentrates on professional and trustworthy for example, the result is going to be a very different ad from ideas that are based on outraged and creative. Both are on brand, but if the final decision is a pick and mix, you or your Communications Manager might well end up being disappointed.

4. Set your target as 'raising as much money as possible'

I probably find this the most irritating of all the great 5 briefing sins. I remember a trainee planner who once worked at Bluefrog always used to complain about having to set targets as "it's not going to make the creatives work any harder".

He was right. It wouldn't.

But what it forced him to do, was work out what was possible and look at the strategic options available. Not setting targets shows no strategic insight.

It's all too easy when writing a brief to simply look at what happened last time and add on a little to response rates and income. But great creative work is not just down to good ideas. It requires a good strategy too. Working out what your audience can give is as important as knowing what motivates them.

Ask the right people for £5,000 and you will get it. Ask the wrong people for £5,000 and you will lose them for ever.

Your targets are another way to define your audience. Use it strategically and your creatives will reward you.

5. Put as much as possible in your single-minded proposition.

The brief must be single-minded. If your strategy has not shown you what form your core

communication message should take, you need more thinking time. The broader you make your proposition, the more you abdicate choice to the creatives and the more you increase the likelihood of the work being wrong.

Do say: Your gift of £15 could answer a child's call for help.

Don't say: A gift of £15 is the average cost of a fully trained counsellor taking a call from a child who is concerned and seeking advice about either bullying, abuse, family strife, drugs, relationships or a wide range of issues that impact on young people aged between five and sixteen.

And finally

A brief should offer guidance, but not tell the creative team exactly what to do. It is there to give the team a framework in which their imaginations can play. The brief writer sets the problem, the creative team come up with the solution.

Remember that, and coming up with great creative work should be a piece of cake (groan).

Tags In

The Essentials

Crack the Code to Regular Giving: Insights, Strategies, and a Special Giveaway!

‘Tis Halloween. Keep to the light and beware the Four Fundraisers of the Apocalypse!

Why do people give? The Donor Participation Project with Louis Diez.

A guide to fundraising on the back of a postcard

What does the latest research tell us about the state of fundraising?