Write a soap opera, not a news story

For the best part of thirty years, Eastenders has dominated the TV ratings.

The Christmas episode from back in 1986 attracted over 30 million viewers and still retains the record for Britain's most watched TV show. And I bet this Christmas, it will be there at the top of the ratings yet again.

As fundraisers, it's not something than we should ignore.

Since the days of Aristotle we've known that to emotionally engage an audience, a great story needs three important elements – a beginning, a middle and an end.

- At the beginning we'll meet the hero, the figure on whose fate our interest in the story will come to rest.

- In the middle we see our hero overcome the obstacles that stand in the way of his or her goal.

- And finally, we get our pay off and we find out whether our hero succeeds or fails.

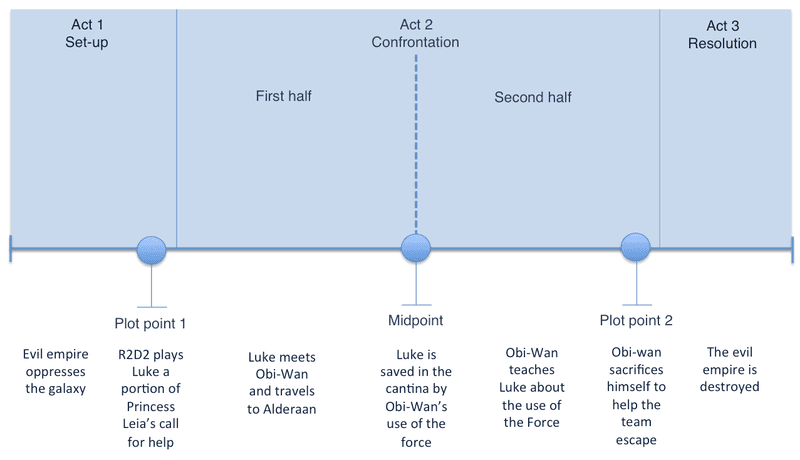

Syd Field, who is seen as the godfather of Hollywood's story template created a paradigm to help illustrate how this three-act structure works for successful films. Here's an example featuring Star Wars…

You'll notice that the middle – the confrontation – is twice as long as either the beginning or the end. And there are two plot points designed to capture the audience's interest to ensure they carry on watching as the next act begins.

Take any soap opera and you'll find a never ending stream of stories that follow this simple structure, which leaves me wondering why fundraisers don't borrow this approach when building communication programmes for donors.

Any decent appeal will usually have a central character who is in need of help to overcome a problem. The pack or website will introduce them and give us a good description of the perils they face as they fight a disease or struggle to overcome poverty. And…well…that's usually it.

The donor will send in a gift and perhaps receive a thank you letter or email that was written a few months (or years) ago. If they are particularly lucky, they might find out more about the project from a newsletter sent later in the year.

But more than likely, the next communication will be another pack asking for a donation that features a different area of the organisation's work.

And that's the problem.

Fundraising stories are a little more complicated than those used by the entertainment industry. That's because the hero is actually the person who is reading our appeals – the donor.

When they are repeatedly refused the chance to find out what happens in the third-act, they can justifiably feel unsatisfied.

It would be a little like your mum coming in and turning off the TV just as the Rebel Alliance is about to attack the Death Star. Yes, we can probably guess what happens in the end. But it's not the same is it? Particularly if we think we are in the seat of Luke's X-wing fighter.

So why does it happen?

Far too often, appeals are so packed full of stats and factual information that we can forget that we aren't just informing, we are engaging as well. And no amount of statistics will beat a great emotional story when it comes to raising money.

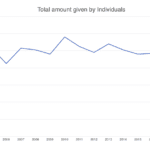

Which brings me neatly to a rather important statistic that's just been published by nfpSynergy.

61% of the people they questioned said the thought that too little of their donation was going to the cause put them off giving.

Because they didn't know what happened to their gift, they thought the worst – that it was mis-used or wasted.

It's pretty damning, considering how sophisticated fundraising has supposed to have become over the last few decades. It indicates that we are still getting the basics wrong.

But perhaps Eastenders might show us a solution?

It features a cast that we care about. The production team introduce new characters carefully and sparingly. And rather than have a different story for every episode, the series is paced so plot lines develop over weeks and months. As a story reaches it's climax and comes to an end, one or two more are bubbling away, ready to take it's place. Though story lines finish, the show never does. And viewers stick with it week after week, month after month and year after year.

So rather than constantly introducing completely new projects and building communication programmes based on when we need to ask for donations, or when we want to send out newsletters or launch a new campaign, we should build an emotional journey that carries the donor along with us, placing them at the centre of what we do.

That means featuring the same work in appeals, newsletters and on the website. It means we focus on building a narrative over time. And, as a result, it means showing donors the outcomes that are relevant to their experience of the organisation – what they have given to.

That way we might just get donors looking forward to our appeals.

If it's good enough for Dot Cotton, it's good enough for us.